The British Museum is about to open its doors to the first ever major exhibition in Britain devoted to the history of Indigenous Australia. Enduring Civilisation will showcase more than 170 startling and mostly never previously exhibited Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander objects, largely from the British Museum’s collections. The exhibition is curated by Gaye Sculthorpe, the British Museum’s Curator of Oceania. Sculthorpe is herself of Tasmanian Aboriginal descent.

Difficult to ignore with such a show is the matter of repatriation, made resonant by ongoing debates around the British Museum’s continued possession of the Parthenon (Elgin) marbles. The British Museum holds some 6,000 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander objects (dated between 1770 and 2015) and Aboriginal people have rightly begun to call for some of them to be returned.

The museum may not speak up about this thorny issue, but others are, gearing up for the anticipated showdown in November when many of the objects travel to Australia to be shown as part of the related exhibition, Encounters, at the National Museum in Canberra.

Elgin shadows

Aboriginal activists such as Gary Murray, Henrietta Fourmile Marrie and Gary Foley have particularly brought the issue to attention. And it’s little wonder that things look to get heated. In 2004 there was a controversy in Australia over the attempted “seizure” or reclaiming of the 19th century Dja Dja Wurrung bark etching and an emu figure of bark, on loan from the British Museum, by members of the Victorian Aboriginal community. They used federal Aboriginal Cultural Heritage legislation to prevent the re-export of the barks while they were on loan to Museum Victoria. They were eventually returned to the UK in 2005.

The attempted seizure caused widespread alarm in European and Australian museums and led to the enactment of anti-seizure laws in 2013. These ensure that objects that travel to Australia to approved cultural institutions will be returned. But the same barks will likely be travelling to Canberra in November, and we may see a reprise of the 2004 protests. The media are certainly gearing up for this.

Murray and Foley are right to call for repatriation – the objects should be returned at some stage, where possible. But it’s unlikely that wholesale repatriation will happen any time soon. And such concerns about the anticipated protest in Canberra and the ever-present shadow of the Elgin marbles tend to pull focus from the exhibition in London and its broader goal of education – and its progressive, indigenous agenda, deftly led by Sculthorpe.

Conversation starters

Sculthorpe is no stranger to these conflagrations and negotiates the tensions as an Aboriginal activist, a museum professional, and the first Aboriginal senior employee at the British Museum. While senior curator at Museum Victoria in the 1990s, Sculthorpe and others developed policies on repatriation and helped negotiate some of the early repatriation of human remains to Aboriginal communities in Victoria.

Considering the British Museum’s heavy imperial legacy, just getting the objects out into the light of day is a major achievement. Doing so may kick-start a crucial debate about how these cultural collections might be interpreted, where they should be housed and how the issues of multiple original owners should be addressed. And the approaching visit of an Indigenous delegation to the British Museum, supported by the National Museum of Australia, will further encourage such a debate.

The British Museum’s description of itself as a “museum of the world, for the world” is perhaps a little vainglorious in its universalising and enlightenment intentions, but there may be something in it. Some Aboriginal people want their cultural heritage back, while others want it to be seen by the world. As Neil Carter of the Gooniiyand and Kidji nation says:

Nobody knows about our culture. You go to England and ask people on the street if they know about our culture and they know nothing. These things in museums… they should be used to educate people overseas…if museums are serious about respecting Aboriginal culture.

Translation

Indigenous insider activists working within institutions such as the British Museum can radically alter ways of seeing and offer new worldviews to unsuspecting European audiences. Such an education is crucial if repatriation efforts are to succeed.

British and other Europeans know very little about Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander culture and history. Terms such as “goanna”, “dugong”, “Dreamings”, “barramundi” and indeed the Aboriginal concept of “country”, have to be explained. Sculthorpe spoke of this particular difficulty to me:

In institutions devoted largely to art historical and archaeological approaches, and with an audience used to seeing societies being organised through chronological frameworks, understanding societies which emphasise complex social relationships, reciprocity, seasonality, and religious beliefs based on connection with the land and sea is not easy to grasp.

Encouraging this cultural translation, then, is hard, political work. Audience members will discover moments of powerful and subversive activism in the exhibition’s curatorial vision. This relates not only to the objects and artwork selected, the stories they tell, but also to their arrangement, the meaning they convey in new contexts. The representation of time itself will be radical for some. To pull something off as big as this requires an indigenous-centred worldview.

Objects tell tales

Above all Sculthorpe hopes the exhibition will educate the UK public about the diversity of Indigenous culture and its history of engagement with outsiders. She is also keen to highlight how the legacy of the past affects ongoing issues facing Indigenous Australians today:

While Australians generally learn about a historic relationship with Britain, contemporary Britons have little knowledge of Australian history and the changing place of Indigenous Australians within the nation state of Australia since 1788. They are often shocked to learn how recent some of the ‘difficult’ history is.

So the exhibition pulls no punches on the issue of violence. Displayed, for example, is Aboriginal resistance leader Jandamarra’s boomerang, telling the story of the Bunuba resistance in the Napier Range in the Kimberley, North Western Australia, during the mid-1890s. It was traditionally thought that Indigenous people put up little resistance – and so these exhibits tell an important story simply by being featured.

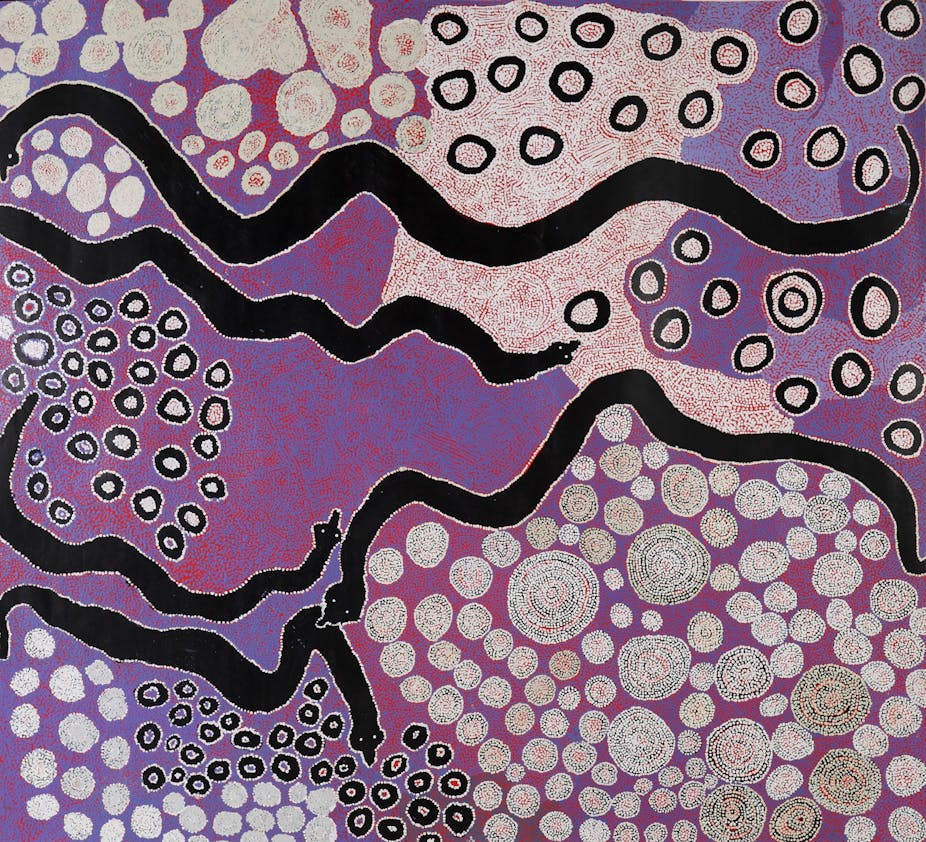

And there’s Queenie McKenzie’s Mistake Creek Massacre, which depicts the murder of up to eight indigenous men, women and children in 1915. The artwork makes a powerful political statement simply by being shown. It sends a message not only about frontier violence but also about recent censorship.

The painting was acquired by the National Museum of Australia a while ago, but not registered into its collection, nor displayed, until very recently. A casualty of the “history wars” in Australia, this was due to internal disagreements as to whether it should be shown as part of the national narrative.

Or there’s the now infamous wooden shield dropped by a Gweagal man when shot by Captain James Cook’s crew in a violent first encounter at Botany Bay in 1770, near present day Sydney. Once it sat in the British Museum’s “Enlightenment gallery” as a foundational treasure. Now the shield sits midway though this new exhibition, but in a very different light: it is answered by a contemporary photographic work by another Cook – Michael Cook depicts Cook’s first landing in Australia.

Cook mimics the moment of the first “discovery” by showing himself dressed as “Cook”. Yet this Cook is Aboriginal. As he steps ashore inaugurating European historical time in a timeless land – as the European narrative convention goes – Michael’s Captain Cook is already Aboriginal. In a form of dangerous visual and linguistic play, Michael “Cook” reclaims the very founding moment of the Australian nation, subverting the entrenched discovery narrative of Australian history.

“Cook” shows us there are many forms of political activism; it comes in myriad guises and is never a zero-sum game. While some protest from the outside and rightly reopen the public debate on repatriation, others, like Sculthorpe, work on the inside. And in the spectrum of protest and change, none need trump the other.