The ever-expanding gig economy has brought with it the rise of the independent contractor, from delivery drivers to personal shoppers and dog walkers. Compared to traditional employees, independent contractors are classified as self-employed and do not benefit from a minimum wage, paid time off, or other protections. This kind of work arrangement is becoming increasingly common, with a recent study showing 20% of professionals surveyed are considering switching to independent contract work.

Growing popularity has also raised questions about how to appropriately categorise and regulate workers in the gig economy. In France and the UK, courts have held that rideshare drivers are employees entitled to protections like a minimum wage and paid time off. In the US, states such as Massachusetts viewing rideshare drivers as employees, while in California, a similar proposition failed to pass.

The promises and perils of limitless flexibility

Gig economy companies have a clear interest in influencing these public debates, as was the case in California, and have gone so far as to pay economists in the United States, Germany, and France to produce research painting independent contractor arrangements in a favourable light. Gig economy companies often highlight the freedom workers have to set their own schedule as one key reason to preserve the independent contractor status. For example, Uber’s website seeks to recruit drivers by highlighting the flexibility their app offers, complete with statistics about how much current drivers value this autonomy. DoorDash and Instacart make similar claims on their websites.

But there is a downside to all this flexibility that is rarely discussed. Instead of an hourly rate or salary, independent contractors are paid for each task they complete with no minimum wage protections. Without guaranteed income, these workers experience “pay volatility”, or frequent changes in earnings over time. As a researcher interested in uncovering the ways that work affects our lives outside of work, I wanted to understand what impact pay volatility has on workers’ health. I recently conducted three studies dedicated to answering this question.

Headaches, back aches, and stomach problems

In my study, I recruited 375 gig workers from across the United States using Amazon’s Mechanical Turk (MTurk), an online platform where workers complete small tasks for a fee. Because these workers are paid varying rates for each task they complete, they experience volatility in their pay. As one participant said, “I can make $80 one day and barely hit $15 the next. It is very unpredictable.” Assuming an eight-hour workday, that’s like switching between earning $10/hour on one day and $1.88/hour the next. I focused only on “dedicated” MTurkers – those who spent at least 20 hours per week on the platform and completed at least 1,000 tasks – and surveyed them over the course of three weeks.

My findings showed that gig workers who reported more volatility in their pay also tended to report more physical symptoms like headaches, back aches, and stomach problems. The reason why? Workers experiencing more pay volatility were more concerned about making ends meet and were preoccupied with thoughts about their personal finances. Dealing with pay volatility means never knowing how much money you’ll make in a given week or month, and that insecurity makes it difficult to cope with ordinary expenses. As one participant described, they like working from home on their own time, but:

“Mturk is too unpredictable in terms of the money and effort required that it becomes frustrating and depressing.”

This challenge seemed to weigh on workers, enough to impact their physical health.

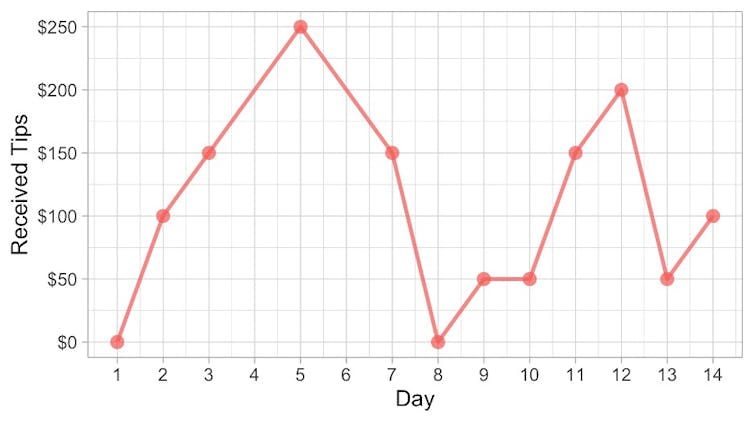

While the problem of pay volatility is clearly relevant for gig workers, they aren’t the only ones who experience it. People who rely on tips, such as restaurant servers, bartenders, valets, and hairdressers, also have constantly changing take-home pay. In a second study, I asked 85 tipped workers in the US about their earnings and health every day for two weeks. Here is one participant from that study reporting the tips they earned each day, underscoring how much volatility can exist for some:

Results indicated that earning more in tips on any given day didn’t make people feel better or worse that evening. But experiencing more volatility in tips over the two weeks was related to more physical symptoms and greater insomnia.

One thing that gig and tipped workers have in common is that they often have lower-than-average income. It might be that pay volatility is not harmful on its own, but only when coupled with low income. After all, Elon Musk probably wasn’t losing much sleep when Tesla shares recently dropped, even if the effect on his net worth was substantial. Hard-pressed to find a sample of billionaires willing to complete my surveys, I conducted a third study with 252 higher-paid workers in sales, finance, and marketing in the United States. Commissions and bonuses are common in these industries, meaning that workers still experience pay volatility even if their income is higher. While the effects were not as strong, I saw the same pattern where workers who were more dependent on volatile forms of pay reported more physical symptoms and worse sleep.

I also considered how workers could protect themselves from the harmful effects of pay volatility. Mindfulness, for example, refers to one’s ability to focus on the present moment instead of worrying about the future and thinking about the past. Although people who are more mindful tend to show resilience in the face of stress, they were equally affected by pay volatility in my study. Workers who were able to save a larger percent of their take-home pay were also similarly affected by pay volatility. These results show that pay volatility is equally harmful for most people. The only factor that actually weakened the observed effects of pay volatility was individuals’ reliance on volatile sources of pay. When volatile pay made up a smaller percentage of their total income, pay volatility didn’t seem to impact their health or sleep.

Hidden costs demand consideration

So what can be done? First, lawmakers need to consider both the benefits and drawbacks of these independent contractor work arrangements. The benefits like flexibility and job creation are well advertised by gig economy companies, but there are also hidden costs that receive less attention. As one participant in my survey stated:

“There are no safeguards in place for workers to guarantee a fair wage on any tasks which, as you can imagine, is probably the one singular aspect of working that produces the most stress, angst and anxiety.”

Ensuring stronger legal protections for independent contractors can help create these safeguards.

Second, companies that employ independent contractors or pay workers based on piece-rate or commissions should carefully consider whether the perceived benefits to motivation or performance outweigh the costs to worker health. Aside from this economic calculation, there is also a moral imperative to offer decent work and preserve good health and well-being among employees, in line with UN Sustainable Development Goals.

Third, companies could strike a balance by reducing workers’ reliance on volatile forms of pay, offering more substantial base pay instead. This strategy should weaken the link between pay volatility and health according to my findings. Overall, it’s clear that while work arrangements popularised by the gig economy hold benefits, we must also consider hidden costs and move toward improving conditions for this substantial swath of the population.