In the second instalment of Biology and Blame, Neil Levy considers how neuroscience can affect legal judgements.

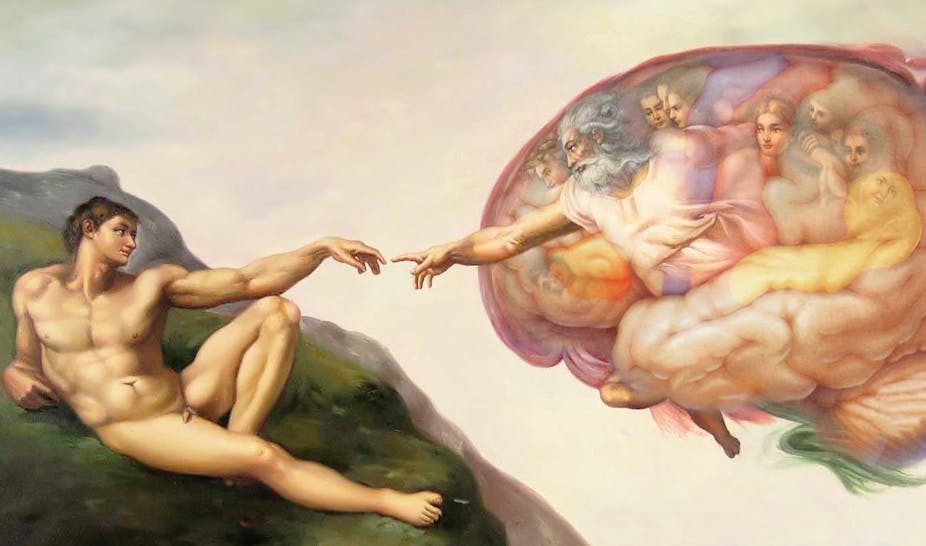

Can human beings still be held responsible in the age of neuroscience?

Some people say no: they say once we understand how the brain processes information and thereby causes behaviour, there’s nothing left over for the person to do.

This argument has not impressed philosophers, who say there doesn’t need to be anything left for the person to do in order to be responsible. People are not anything over and above the causal systems involved in information processing, we are our brains (plus some other, equally physical stuff).

We are responsible if our information processing systems are suitably attuned to reasons, most philosophers think.

There are big philosophical debates concerning what it takes to be suitably attuned to reasons, and whether this is really enough for responsibility. But I want to set those debates aside here.

It’s more interesting to ask what we can learn from neuroscience about the nature of responsibility and about when we’re responsible. Even if neuroscience doesn’t tell us that no one is ever responsible, it might be able to tell us if particular people are responsible for particular actions.

A worthy case study

Consider a case like this: early one morning in 1987, a Canadian man named Ken Parks got up from the sofa where he had fallen asleep and drove to his parents’-in-law house.

There he stabbed them both before driving to the police station, where he told police he thought he had killed someone. He had: his mother-in-law died from her injuries.

Parks had no discernible motive for his crime and no history of violence. He claimed he was sleepwalking throughout the whole thing. Should we believe him?

We can’t go back in time and get direct evidence concerning whether he was sleepwalking. But there’s plenty of indirect evidence available.

The fact the action was out of character for Parks is one piece of evidence. He also had a childhood history of sleepwalking. Other pieces of evidence came from science: two separate polysomnograms (a test used for study and diagnosis in sleep medicine) indicated sleep abnormalities.

Assuming we believe him, why should sleepwalking excuse murder? A first attempt at an answer might be that sleepwalkers don’t know what they’re doing. Maybe that answer is right, but we need to take care in assessing it.

Sleepwalkers don’t act randomly or blindly, nor are their actions mere reflexes. Instead, they act intelligently.

Ken Parks drove 23 kilometres through suburban streets: that doesn’t happen by accident. Rather it indicates an impressive degree of control over his behaviour.

Parks responded to information in ways that made sense, turning the steering wheel to follow the road, braking and accelerating to avoid obstacles, and so on. So why not think he’s responsible for his actions?

Guilty or not?

Here neuroscience is relevant once again. There’s a great deal of evidence that consciousness, which is greatly diminished in sleepwalking, plays an important role in integrating information.

When we are conscious of what we’re doing, the information is simultaneously available to a wide range of different brain regions involved in behaviour. When we’re less conscious, the information is only available to a small number of these regions.

When information is available to only a small number of brain regions, we can still respond to it in a habitual kind of way. That’s why Ken Parks was able to drive his car: he (like most of us) had acquired driving habits.

It’s because of these habits we’re able to drive while daydreaming or singing along with the radio, hardly aware of what we’re doing.

But the information concerning what he was doing was not broadly available to his mind. That’s important, because he wasn’t able to control his behaviour in the light of all his beliefs. He responded automatically, without being able to ask himself whether he valued what he was doing.

A whole range of information which would normally have stopped him (screams, the sight of blood, his mother-in-law’s terrified face) couldn’t interact with the mechanisms causing his actions.

The Canadian court found Parks not guilty on the charge of murder (an acquittal later upheld by the Supreme Court). I think they were right to do so.

Neuroscience provides evidence that in the absence of consciousness, we can’t control our behaviour in the light of our values. And that’s a good reason to excuse us.

This is the second article in our series Biology and Blame. Click on the links below to read other pieces:

Part one – Genes made me do it: genetics, responsibility and criminal law

Part three - Psychiatry’s fight for a place in defining criminal responsibility

Part four – Looking for psychopaths in all the wrong places: fMRI in court

Part five - Why shouldn’t addiction be a defence to low-level crime?

Part six – Natural born killers: brain shape, behaviour and the history of phrenology

Part seven - Put down the smart drugs – cognitive enhancement is ethically risky business