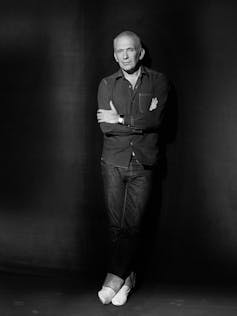

French fashion designer Jean Paul Gaultier – whose designs are featured at the National Gallery of Victoria (NGV) until February 2015 – has always had an unsettling relationship with museum fashion exhibitions.

For decades Gaultier resisted production of the classic retrospective exhibition surveying his design enterprises. Perhaps he was concerned with the concept of an environment occupied with rows of dressed mannequins aligned in chronological order, which seemed far removed from the contemporary designer’s engagement with street style or flamboyant nightclub culture.

Gaultier associated the “blockbuster” museum exhibition, which looks back over a large body of work recognising success and critical acclaim, with dead designers removed from fashion currency or relevance.

But the fashion context is a challenging one, in representation of human experience, appearance, narratives about circulation and consumption, transience, cultural conditions, design process and thinking.

The contemporary fashion exhibition imparts an influential voice about design practice. Museum media circulates fashion ideas to a wide range of people and explores fashion’s relationship to other things.

Bakers and seamstresses

Ten years ago there was an overview of Gaultier’s most famous designs held at Cartier Foundation of Contemporary Art in Paris. The exhibition – Pain Couture (High Fashion Bread) – focused attention upon artisanal practice, yet displayed no fashionable clothes.

Instead of showing examples from past and present clothing collections, the traditional Parisian crafts of baking and sewing were united when Gaultier collaborated with French bakers to knead, craft and bake his most famous clothing designs.

Bread garments offered an understanding of fashion concerned with making processes and detail of form. Well-known garments represented included Madonna’s iconic bra dress – which featured brioche cups. The abstraction of garments into bread forms was imaginative and quirky.

The exhibition drew attention to unique bread-making practices, which were threatened by generic bread franchises operating in Paris. In this context, transience was the design solution – and ran contrary to the “permanance” associated with museums.

The garments were destined to gradually harden and be reduced to crumbs. When the show was over there was nothing left to archive.

Therefore one might be curious why Gaultier finally decided to become involved with and support the large retrospective at the NGV this year. After all, this show exemplifies the ceaseless activity of fashion design practices, set in museum conditions.

Like Pain Couture, the exhibition is mesmerising because of its close encounters with artisanal practices. In both, the attention to detail is profound.

Gaultier’s design practice

The NGV exhibition is engaged with real clothing, drawn from the designer’s archive. The assemblage of clothes and related imagery shows the power of fashion to imaginatively and provocatively dress the body. The garments on display embody complex dress ideas – and they epitomise the best European fabrication techniques.

The exhibition’s allure is found in selection of so many “recognised” garments. We see items that have become familiar thanks to the celebrities who have worn them. Appropriately, to display the 160 garments and associated materials that make up the exhibition, the museum is transformed into catwalk, nightclub, streetscape and boudoir.

Gaultier describes himself as an artisan because, like the bread-maker, his enterprise creates high-quality, distinctive products using traditional or labour intensive methods.

But fashion is a collective practice, so Gaultier’s artisanal enterprise involves scores of people working across design, production and distribution areas. This is an industry of scale not singularity.

Mannequins enlivened by projected animated (and talking) faces reference the human experience of wearing clothes. There is plenty of novel interactive engagement with display mannequins. This too subverts the museum space as the mannequins greet or disturb the passerby with an occasional wink or song.

But what impression of Gaultier’s design practice does the NGV show leave?

Gaultier’s creations are playful, contest ordered systems of dress with idiosyncratic clothing juxtapositions. We see assemblages which mix genres, gender associations, recycle fashion history and cultural dress traditions. The clothes adopt elements of satire, visual puns and the ridiculous to critique what we wear.

There is a curious tension and synergy between provocative garments produced in earlier decades with flamboyant and intricately detailed creations forged for haute couture.

In late 1970s-1980s Gaultier was generally described by fashion journalists as an enfant terrible because his collections provoked stereotypical understandings of clothing from standard dress archetypes, included distinctions between outerwear and underwear to gender associations with business suits and skirts.

A male-skirted suit designed in 1985 – on display – was designed as a practical alternative to trousers, but it was commercially unsuccessful. It was viewed as a novelty, an attempt to shock the fashion world. The uptake was slow; Sarah Mower writing for Arena magazine noted only 3,000 suits were produced worldwide.

Haute couture garments also attract notoriety. Jean Paul Gaultier first showed in the Paris haute couture collections in 1997, when currency of this exclusive mode was being threatened by diminishing markets.

Yet craftsmanship is only one aspect of Gaultier’s foray into haute couture, where he injected into this fashion arena different readings of beauty and gender, with collections worn by models like Austrian drag singer Conchita Wurst.

On display, the taffeta evening gown with “leopard skin” bead embroidery with rhinestone claws from Russia collection autumn/winter 1997-98 for is recognised in the exhibition by noting more than 1,000 hours of workmanship in its making.

The trompe l’oeil beaded leopard fur dress shows the artisanal practices of haute couture through invention of new surfaces and manipulation of diverse materials. Rich technical palettes are built up from applied decoration using beads, tucks, embroidery, drapery and pleating.

In an industry dominated by fast fashion, homogenised styling and designed obsolescence, it is timely that an exhibition of clothes reminds us of the power of artisanal practice – and that great fashion design is thought-provoking and transformative.

The Fashion World of Jean Paul Gaultier: From the Sidewalk to the Catwalk is on show at the National Gallery of Victoria until February 8, 2015.