A landmark new ruling by the Supreme Court in the UK is a tentative but positive step towards the abolition of a controversial law called joint enterprise. Our recent research suggests that changes in the use of the law – which allowed people to be convicted of a crime even if it is not proven they committed it – are likely to bring relief to the black community.

The Supreme Court recognised that “foresight” that a crime might occur cannot be enough to secure conviction. This means that prosecution teams will now have to demonstrate “intent” rather than, as we have found, relying upon a series of racial stereotypes.

Our analysis was drawn from a survey of nearly 250 joint enterprise prisoners, a number of case studies and official criminal justice data on gangs and violence.

We asked prisoners about their relationship with the events of the offence, and to those identified as their co-defendants. Their answers were varied, and in a number of cases prisoners recognised culpability for lesser offences. Yet it was concerning that in nearly half (45%) of the 250 cases we surveyed, the prisoners were not at the scene of the crime. In these cases, this principle of foresight and its relationship to intent and culpability was key to connecting them to the crime and securing a joint enterprise conviction.

‘Gang’ stereotypes used in court

Evidence submitted to the 2014 House of Commons justice select committee by academics from Cambridge University already indicated that joint enterprise may be disproportionately experienced by black and minority ethnic people. The researchers speculated that this may be due to an association that exists in the minds of the police, prosecutors and juries between young black and minority ethnic people and gangs.

We asked the joint enterprise prisoners about the evidence presented against them in court, in particular, whether there had been any reference to “gangs”. Four out of five – or 80% – of the black and minority ethnic respondents told us that the concept of the “gang” was drawn upon by the prosecution in their court case. This figure was significantly lower for white prisoners, as the graph below shows.

For white prisoners, in many cases no further evidence was used to demonstrate the gang narrative. But for the black and minority ethnic prisoners, a range of strategies and stereotypes were brought into the courtroom by prosecutors. “Gang names” such as “Johnson Crew”, “Gooch” or “Burger Bar” were referred to by the prosecution, depending on the area.

In other cases, the prosecution linked defendants to local neighbourhoods often highlighted in media stories about violence. In the case of black and minority ethnic defendants, our interviewees said that photographs on social media, music videos and rap lyrics were also used by prosecution teams of evidence of gang involvement.

Our research reveals that such associations, used to imply “common purpose” between the defendant and the person who carried out the crime, rely heavily upon racial stereotypes of young black men being involved with violent crime and gangs. Yet the overwhelming majority of joint enterprise prisoners, from all ethnicities, told us that they were not gang members and that this was a “made up feature of the prosecution case”.

One told us: “I have never been in a gang. I was a family man who had a good job.” Another said:

One of my [co-defendants] was an active ‘gang member’ but I was not. I was a friend of a gang member so I was also judged to be a gang member.

Disrupting dangerous associations

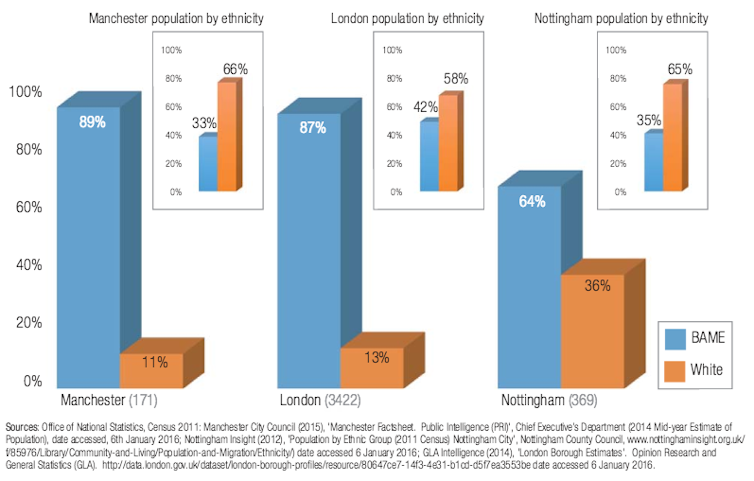

Our analysis of official police data also compared the ethnic profile of people who had been flagged as being involved with gangs to the ethnicity of those convicted of serious violent offences.

While we found that the gang label is disproportionately attributed to young black men on police databases in Manchester, Nottingham and London, the ethnic profile of those accused or convicted of serious violence shows the opposite. Black people are not responsible for the majority of serious violence in these cities. In Manchester, for example, 89% of the gang database was black or minority ethnic, but only 23% of those convicted of serious youth violence were.

The government is starting to take note. At the end of January, Labour MP David Lammy was asked by the prime minister to carry out a review of the evidence of possible bias against black defendants and other ethnic minorities.

The Supreme Court’s new ruling marks a significant step for the campaign led by Joint Enterprise – Not Guilty by Association (JENGbA) to righting many injustices caused by joint enterprise. The campaign group have long argued that its use is racist.

Yet joint enterprise prosecutions driven by racist “gang” stereotypes are just one mechanism driving disproportionate numbers of black people being incarcerated: over 40% of young people in prison in England and Wales are from black minority ethnic communities. In order for joint enterprise not to be replaced by other forms of policing, prosecution or sentencing that overcriminalise young black men, we must challenge the racist tendencies at the heart of our criminal justice system.