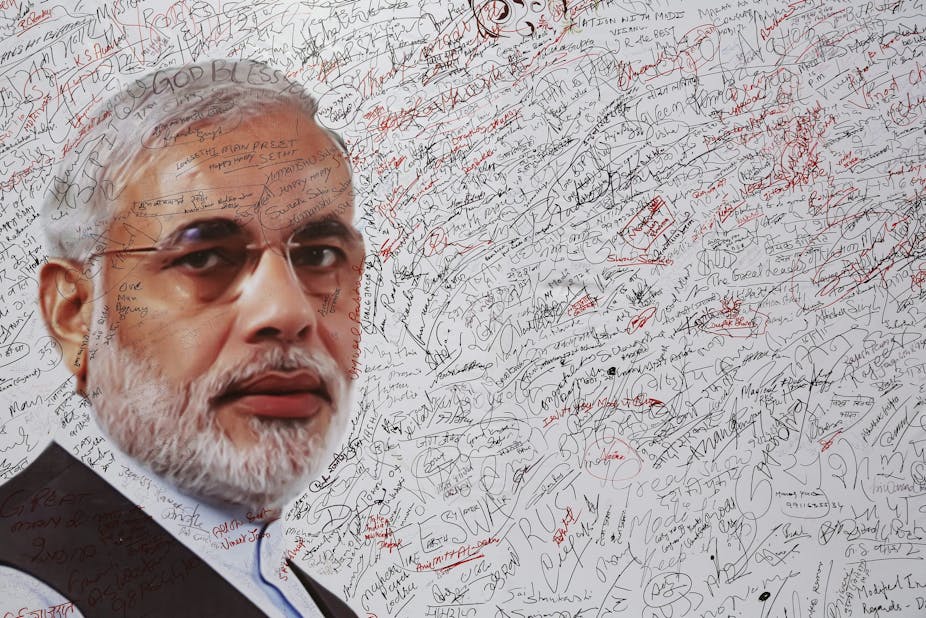

India’s election, which was won convincingly by the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), revolved around only one man: India’s next prime minister, Narendra Damodardas Modi.

Modi represents a fascinating turning point in the political history of the world’s largest democracy. He is set to lead a government that promises dramatic changes and reforms. But who is he?

Early life: a ‘Chai Wallah’

Modi, the third of six children, grew up in Vadnagar, a town in present-day Gujarat. After assisting his father selling tea, the teenage Modi himself became a Chai Wallah (tea seller) near a bus terminus.

Modi was an average student at school but had an interest in theatre, which probably helped him project as a leader when he entered politics. He completed his tertiary studies in political science from Delhi University through a distance education program and holds a master of political science from Gujarat University.

Modi was engaged at the age of 13 and married at the age of 18, though this marriage was never consummated. Despite having described himself as unmarried at the past four elections, he declared himself as married while nominating for the 2014 election, which caused some controversy.

Modi’s ideological training

At the age of eight, Modi began volunteering with the Rashtriya Swayamsewak Sangh (RSS). The RSS is the ideological inspiration of the BJP and since joining, Modi has been inclined to the ideology of Hindu nationalism. He became a full–time RSS pracharak (propagandist) in 1970.

After receiving training at the RSS in Nagpur, Modi worked as an activist for the Akhil Bharatiya Vidyarthi Parishad (ABVP), the student wing of RSS, in Gujarat. During Indira Gandhi’s emergency rule, Modi secretly carried on the RSS’s activities and joined the JP Movement.

Modi joined the BJP in 1985. He has since held many offices in the party and slowly became an important figure in the BJP in Gujarat. His campaign organising skills were praised in the successful campaigns of Murli Manohar Joshi’s Kanyakumari-Srinagar Ekta yatra (Journey for Unity) in the 1991 and 1995 Gujarat elections. Modi became general secretary of the BJP in 1995 and moved to Delhi, but returned to Gujarat in 1998 and was again a central figure in the BJP victory in that year’s state election.

Modi replaced Keshubhai Patel as Gujarat’s chief minister in 2001 amid allegations of corruption as well as a number of by-election defeats for the BJP. Earlier, Modi was offered the deputy chief ministership of Gujarat, but refused to be Patel’s second-in-command.

As chief minister, Modi’s vision of small government and focus on privatisation was in contrast to the RSS’s anti-privatisation and anti-globalisation stance.

2002: the Godhra and Gujarat riots

In February 2002, a train carrying Hindu pilgrims near Godhra station caught fire, killing 59 people. It was speculated that Islamic radicals carried out the attack. This sparked a riot in Gujarat in which nearly 2000 people, mostly Muslims, were killed.

The Modi government’s handling of the riots was questioned, with many stating that Modi didn’t do enough to stop the violence.

In April 2009, the Indian Supreme Court appointed a Special Investigation Team to investigate Modi’s role in the riots. In December 2010, the investigation cleared Modi of wilfully allowing the rioters to rampage through the province.

Despite this, the allegations against Modi continue to stain his reputation. Since the Gujarat riots, arguably no politician in Indian history has faced the same level of criticism as Modi. As a result of the controversy, he was barred from entering the US, though this now appears to have been lifted. US president Barack Obama has invited Modi to the White House since his election victory.

From chief minister to prime minister

Despite the Gujarat riots controversy, Modi won three Gujarat state elections: in 2002, 2007 and 2012. As chief minister, Modi is credited with Gujarat’s economic progress and development. Gujarat’s growth in GDP (an average of 10.1% per year during Modi’s tenure) far outstripped India’s GDP growth over the same period (7.7% per year). The Modi government received accolades for its industrial growth, business and exports.

However, there are contrasting views on Modi’s time as chief minister. Nobel laureate Amartya Sen criticised Modi both as an economic performer and as an administrator, doubting his secular credentials and his record in education and health care.

Other prominent economists such as Jagdish Bhagwati and Arvind Panagariya argue that Gujarat’s social indicators improved from a much lower baseline than other Indian states. They argue that the Modi government’s performance in raising Gujarat’s literacy rates was better than in other Indian states, and the “rapid” improvement of health indicators in Gujarat is evidence that “its progress has not been poor by any means”.

No-one could have imagined that Modi would turn a fragmented parliamentary election into a presidential-style referendum in an era of coalition politics in India. Modi’s mandate, crossing caste, region, gender and demography, will make him one of the most powerful prime ministers in Indian history.

Modi has transformed himself from a Hindu nationalist into a decisive corporate-style administrator. He is now at the centre of global thinking, having been labelled “the man who dines alone”, a “game changer” and a “poet”.

All eyes are now on Modi‘s initiatives to fix the Indian economy, as well as examining how successful he is in leading a nation of 1.2 billion people on a path of progress to achieve India’s “rightful place in the world”.