The electoral uncertainty in South Australia has come to an end, at least for the foreseeable future. To some disbelief, Labor premier Jay Weatherill has managed to overcome the odds – and indeed the polls – to form a minority government.

Weatherill and his Liberal counterpart, Steven Marshall, had been forced into a week of horse trading after South Australians elected a hung parliament on March 15. But isolated by the illness of the key independent Bob Such, Geoff Brock, the other independent MP, decided to seek “stability” by supporting the ALP as a minority government.

In the process, Brock secured the promise of a ministerial post. He will oversee the areas of regional development and local government.

Yet for all the ALP’s euphoria, this could be a short political honeymoon. The Weatherill government faces uncertain times, and an already divided electorate could be unforgiving over the next four years.

Weatherill’s government face three key challenges. First, it needs to revive the state’s economic situation. Marshall and the Liberals worked hard to raise concern about the state’s record level of debt. While Weatherill sought to counter with a more positive assessment, he will be under pressure to show some fiscal restraint.

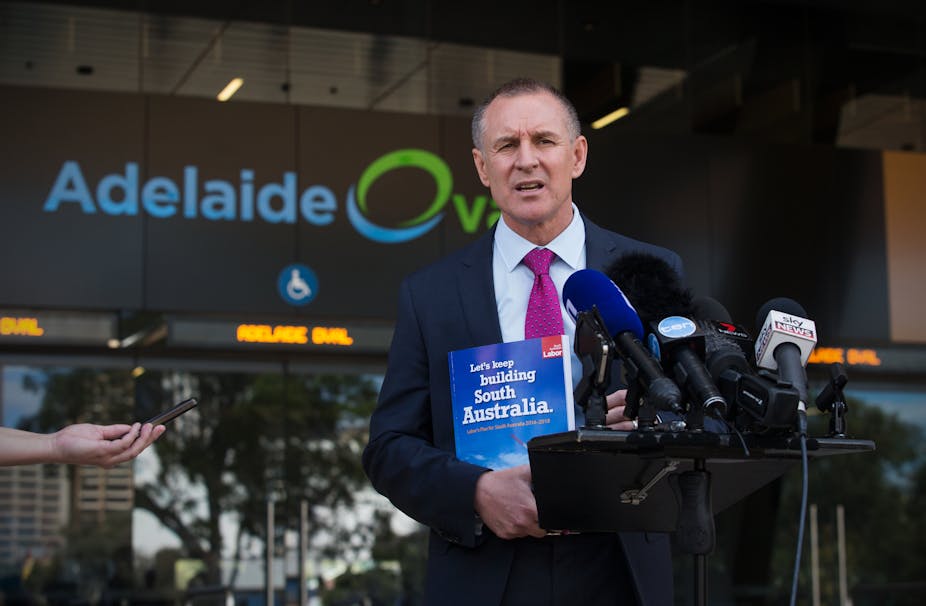

Weatherill’s government is being pushed in two opposing directions. Elected on a promise of “Building a stronger South Australia”, the ALP is committed to keep up its steady stream of state-driven infrastructure building. This is the politics of stimulus, but it has its limits. With the completion of the Adelaide Oval redevelopment, it remains unclear what the next suite of projects are and when they will begin.

Despite his commitment to invest, Weatherill has pledged to return the state finances to surplus by 2015-16. With the unexpected shortfall in GST revenues, this looks unlikely, and the pledge to create a South Australian future fund is an even more distant hope. Weatherill will be under renewed pressure to extend further savings in the public sector.

Marshall’s plan, in contrast to Weatherill’s, was a short-term one, promising a range of tax cuts including cuts to payroll tax. Weatherill will hope his longer vision will also deliver some short-term uplift.

Underpinning the economic situation is the next key challenge for Labor: federal-state relations. With Tasmania now in Liberal hands, South Australia has the only Labor government amid wall-to-wall conservative governments at state and federal level (aside from the ACT). Weatherill portrays this as a strength, in that he won’t be a lackey for prime minister Tony Abbott.

However, too much grandstanding against the federal Liberals could see crucial federal money dry up. And to help Holden workers in South Australia – 1600 people will lose their jobs when the car maker shuts in 2017 – Weatherill’s state money also needs substantial federal investment. In an era when apparently the “age of entitlement” is over, this money will prove even harder to secure.

The third challenge is just as daunting: reform and improvement of public services. If they survive a full term, South Australians will have had 16 years of Labor delivering a range of core public services by the time of the next election. Labor is under to pressure to improve a range of health and education indicators.

As the Debelle Inquiry into sexual abuse at an Adelaide school has shown, South Australia’s education department has a poor reputation with low public confidence. During the campaign, the Liberals also pointed out that educational attainment has been slipping, hence their suggestion to move Year 7 into high school.

In contrast, the ALP pledged to ensure that all South Australian schoolteachers have a masters degree. But this will also require other strategies to improve results and confidence.

In health, the government is under intense pressure to find savings. Brock will play a crucial role here to see that rural services are not adversely affected.

In other key policy areas, such as transport and housing, incumbency means that the government will have to show that Labor has more than a “plan” to improve transport corridors and reduce overall levels of housing stress. Together, these are formidable problems for a minority government to overcome.