Small-scale fishers in Vietnam’s Cau Hai lagoon can’t easily access loans to upgrade or repair the fishing gear they urgently need. Some also want to invest in aquaculture supplies, but lack the start-up capital.

Fifteen years ago, one innovative fisher in the lagoon convinced his friends and neighbours to pool their capital to create a fund for micro-loans. Members could then borrow small sums for specific short-term needs. The fishing association with this micro-loan system is now the envy of neighbouring fishing communities.

Success stories like this are important, but all too infrequent. Efforts to distil sustainability insights from grassroots innovations are growing in communities all over the world — and we need more.

These “seeds” provide valuable insights into how small communities and dedicated individuals can drive positive change.

We recently published our research documenting the ways community-led innovation helps move small-scale fisheries towards sustainability. Cataloguing these building blocks can help others lead changes in their own communities.

Altering research orientations

Concerns about the sustainability of fisheries are well-founded.

Recent estimates confirm that small-scale fisheries — think small vessels (often unmotorized) and low-tech gear, not offshore trawlers — have important global economic value, but they are under threat.

We need a better understanding of how overfishing, bycatch (fish or other marine species caught unintentionally) and habitat damage affect small-scale fisheries. This type of research confirms the urgent need for action, but it is problem-oriented and doesn’t tell us how to resolve challenges facing fisheries.

Lessons from outliers

Many of the fishers in the Cau Hai lagoon, the site of our research, are poor and make harvesting decisions that meet their basic needs. They sometimes use fishing gear that is highly effective but can also be destructive, even though they understand the consequences of their actions.

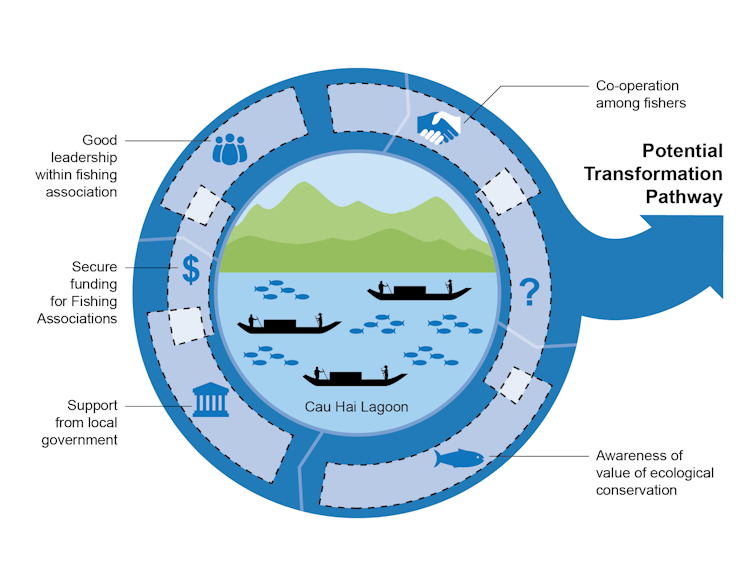

We went looking for the successful outliers and found some common elements, including awareness of the value of ecological conservation, co-operation among fishers, local government support (police monitoring and enforcement of fishing bylaws), secure funding for fishing associations and good leadership.

The fishing association with the micro loans is an example of good leadership and innovative access to funding.

Another fishing association capitalized on communication and personal relationships. Its leader, well-regarded among fellow fishers, government agents and academics, has leveraged support from the local government by regularly attending village council meetings, where he tells local government officials about the issues fishers face, gaining their sympathy.

These may seem like obvious and simple actions, but they are not the norm in the Cau Hai lagoon. If other leaders were to replicate these actions, it would go a long way to securing more government support for enforcing fisheries bylaws.

Building blocks

Elements like these form the building blocks for a sustainable fishery in the Cau Hai lagoon, and they are likely to transform untenable conditions in other locations too.

The building blocks metaphor — steps along a pathway to sustainability — is also a reminder that there is no singular way to work towards sustainability.

Coastal communities will follow different paths in the pursuit of sustainability, but if we look carefully, we are likely to see the building blocks that matter most in each context.

Universal value

We can also apply this type of thinking to the Canadian context to improve fisheries policies and support communities.

Fisheries management in Atlantic Canada and British Columbia face ongoing challenges such as conflict, lost quotas, over-capacity and tensions with owner-operator fleet separation.

The building blocks approach offers a way of thinking about positive steps to work towards sustainability. We can think more about places and fisheries where they have had successes with, for example, reducing bycatch or overfishing.

Sometimes lessons are hiding in plain sight.

There are many communities where individuals and groups are making positive changes to their livelihoods and ecosystems. We need to see Canadian and global fisheries from new perspectives and ask questions that help gather those lessons to build towards success.