Britain’s newspaper editors met in a London hotel last week in a bid to fend off statutory regulation of their activities.

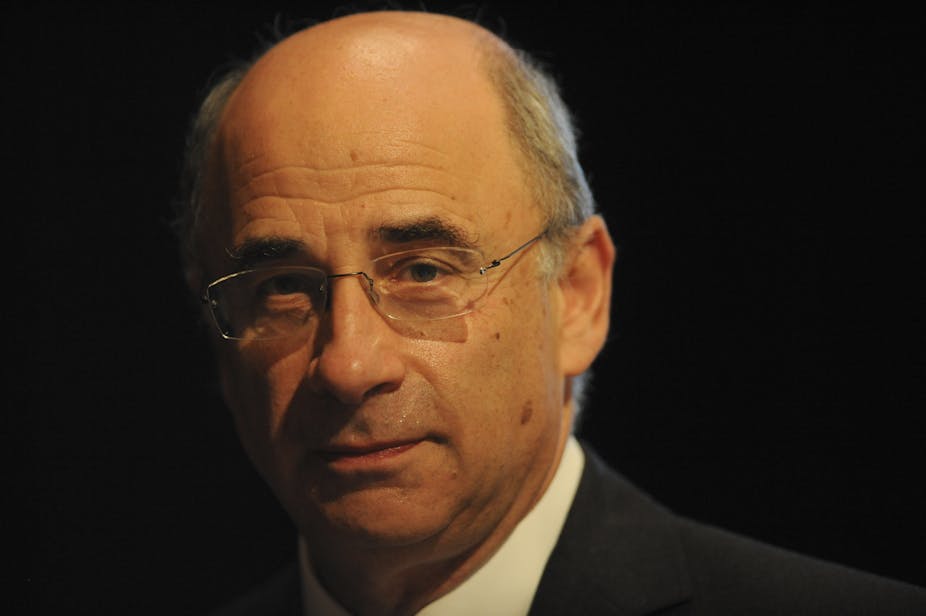

Warned by prime minister David Cameron on Tuesday that unless they accepted all Leveson’s recommendations (short of those relating to the formation of a statutory auditing board on the model of broadcast regulator Ofcom) his government would be obliged to implement the dreaded statutory element, the editors sought to show good faith. We are promised, if not for the first time in British press history, a genuinely effective system of industry self-regulation.

Meantime, the Labour opposition has published its own draft “press freedom and trust” bill, which would task the lord chief justice (head of the judiciary in England) with statutory oversight of any new industry watchdog. Another lord, Baron Anthony Lester of Herne Hill, has proposed a bill with similar statutory underpinning.

And so we have an emerging resolution to this long process of review. The British press will get one more chance to demonstrate their capacity to regulate their own ethical conduct, by applying the Leveson template (minus statutory underpinning for now). In doing so they know that, should they fail to satisfy the government, or public opinion, statutory intervention will follow.

This is less than demanded by Hacked Off and other advocates of statutory regulation (including Labour leader Ed Miliband) and more than the newspapers would have preferred. But the latter clearly understand that they have exhausted the patience of their critics, and seem ready to accept the changes proposed by Leveson as the least worse option.

The victims of phone-hacking, along with the majority in the UK which appears to support statutory underpinning, will probably have to bite the bullet and accept that Cameron is in charge of the process, at least until the next general election is due in 2015. By then, the British public may have lost interest in the phone-hacking scandal.

The clamour for ethical reform of the British press has been cyclical. It comes and goes, triggered by particularly heinous breaches such as the Sun’s coverage of the Hillsborough disaster, or the News of the World’s hacking of murdered school girl Milly Dowler’s phone, before receding from the public agenda. That may be the pattern once again. Then again, given that 2013 will feature ongoing coverage of trials of media executives, journalists, editors and others involved in allegedly corrupt practices, it may remain a key political issue right up until the 2015 election. The phone-hacking scandal, and the flurry of debate and review it provoked, may yet turn out to be a watershed in the history of British press regulation. That will depend not least on how the press behaves in the next two years.

We should all hope that Britain’s newspapers clean up their act and remove the need for statutory intervention. Legal restrictions on the media should always be kept to a minimum in a democracy, for the reasons which have been exhaustively rehearsed in the course of the Leveson process.

Leveson himself acknowledges this in his report, at the same time as he stressed that the great majority of British journalists, most of the time, do a good job. Statutory regulation can not be justified as a punishment for the bad behaviour of some journalists, if it might have adverse impacts on the investigative capacity of all those other journalists who don’t hack phones, bribe police officers or publish private diaries without permission.

Here in Australia, meanwhile, the 2Day affair reminds us that our media are far from squeaky clean in ethical terms. The blithe assumption that it’s jolly good fun to invade the privacy of others, secure confidential medical information by deceit, then broadcast it to the world regardless of the consequences for the victims at the other end, is indicative of a moral deficit at the core of much media practice in this country. The reaction of the Australian public to the story shows, moreover, that our collective tolerance for such behaviour is eroding.

That public tolerance in Britain is thoroughly smashed, and and will take years for the institutional press to regain. The News International phone-hackers, and the managers who allegedly oversaw a culture in which such practices flourished, broke existing laws, and many of them are now paying the price. There are already laws in place to police unacceptable media behaviour, and they should be used to the full before introducing new ones.

This is true also for the internet, largely ignored in Leveson’s report but discussed in his lecture at the Universaity of Technology, Sydney last week, when he suggested the need for new legislation to govern online privacy. He pointed to the recent BBC Newsnight case in the UK, where a report about a leading Tory politician - Lord McAlpine - implicated in child abuse did not name the alleged offender, but created an environment in which the name went viral on Twitter and other social media platforms. A similar outing occurred in relation to the former Australian children’s TV star questioned in the UK on sex abuse allegations last week. He was not named in the mainstream media, in the UK or here in Australia, but his name was easily found by a quick Twitter search.

McAlpine, however, has responded to the false coverage of his case by threatening to take legal action for defamation of character, including against online commentators such as George Monbiot, who unwisely named him in tweets. The BBC, meanwhile, has been thrown into deep crisis by the story, and has already paid a heavy price for not taking more care with its editorial process. And the BBC is heavily regulated by Ofcom, a fact which did not prevent major transgressions from occurring.

The Savile and McAlpine cases show that even the most rigorous legislation of the type imposed on the most respected of public service broadcasters is no guarantee of journalistic incompetence and error leading to gross injustices against innocent individuals.

For the British press, the problem is cultural at its core. The worst offenders in privacy violation have been at the same time the most popular newspapers, their most sordid and intrusive stories soaked up by millions of engrossed readers. The politicians, from Thatcher onward, appear to have turned a blind eye to newsgathering techniques that were often illegal, including stories that directly targeted them.

They did this because they sought editorial support in an environment where newspapers mattered much more than they do now. Proprietors exploited that tolerance to maximise circulations and profits, even if, like the Murdochs, they maintained plausible deniability of involvement in the worst cases.

So there are lessons for the British public, politicians, and media practitioners alike in all of this.

All have played their part in allowing a dysfunctional press culture to persist in the UK, and in making it extremely profitable for companies such as News Corp. If those lessons can be learnt, and cultural shift around media ethics implemented as a result of that reflection, then perhaps the statutory underpinning of regulation recommended by Leveson will not be necessary. If not, then it will be hard for any government to resist.