Few public inquiries have been so closely followed by the British press, or its findings awaited by them with such nervous anticipation as Lord Leveson’s into their culture, practices and ethics.

The waiting is over, however, and Leveson’s four-volume report is now being digested by all stakeholders. Australian media watchers will also be absorbing its conclusions over the weekend, in the knowledge that post-Finkelstein there is pressure for reform of press regulation in this country too. Will Leveson influence the Australian debate?

The inquiry’s conclusions will be disquieting for many, because they use the term “statutory” in relation to the proposed new system of press self-regulation for the UK. Leveson has rejected a proposal for a beefed-up Press Complaints Commission, and argued instead for a legally constituted mechanism which would be “genuinely independent” of the industry.

This would not be statutory press regulation, Leveson insists, and such a body would be clearly distanced from political interference or control, but it would have legal recognition. “What is proposed here,” he writes, “is independent regulation of the press organised by the press, with a statutory verification process to ensure that the required levels of independence and effectiveness are met”.

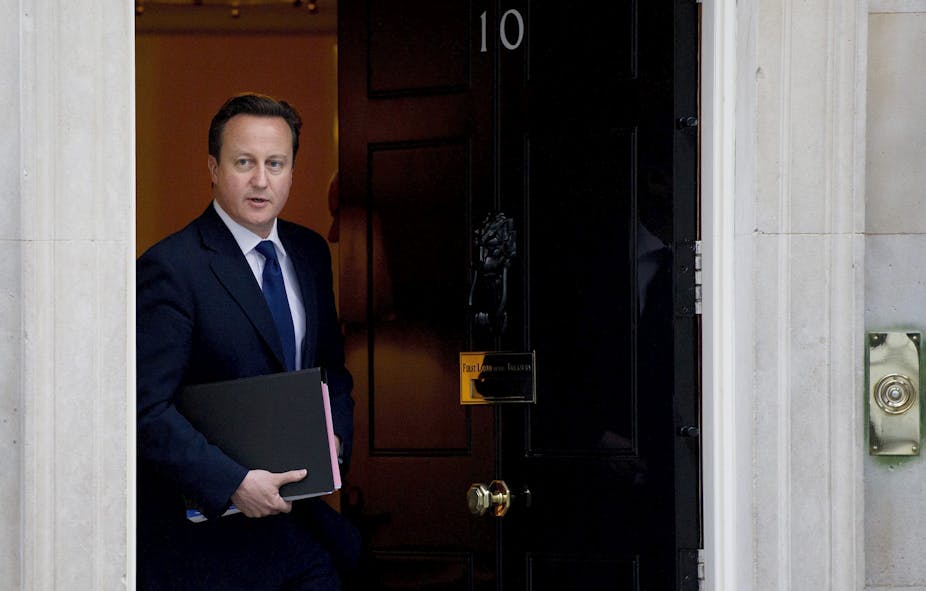

Prime Minister David Cameron, who established the public inquiry, immediately rejected its key finding, on the grounds that such a legal process would “ultimately infringe on free speech and a free press”.

His deputy in the coalition government, Liberal Democrat Nick Clegg, has on the other hand expressed his support for the recommendation, as has the Labour party leader Ed Miliband. What we can say, therefore, is that if the Tories lose the next election, as the opinion polls currently indicate is very likely, something like the system proposed by Leveson will probably come to pass.

This will depend to some extent on the behaviour of the media between now and then, and on the extent to which the victims of phone-hacking - celebrity and non-celebrity alike - keep up the pressure for reform. The coming wave of court cases involving dozens of journalists and editors, including former senior News International executives Rebekah Brooks and Andy Coulson, can also be expected to have a bearing on the public and political mood.

For now, though, Cameron’s preferred option is to declare late opening hours at the last chance saloon, that place of reckoning last invoked in the early 1990s when the British press faced similar criticisms of privacy violation, and the same calls for statutory regulation of their newsgathering and reporting activities. That earlier wave of public revulsion produced the Press Complaints Commission, and a threat from the then-Conservative government that if the British press did not put its own ethical house in order, the law would be invoked.

Twenty years down the track, another Tory prime minister has been required to make the same declaration. Details remain unclear, but it’s reported that the press industry will be given up to a year to propose a non-statutory system of self-regulation that is stronger and more effective than the present PCC model, but falls short of crossing the legal Rubicon so feared by many.

Whether this will be enough to satisfy the almost universal sense of outrage directed towards News International and other press organisations following the phone-hacking scandal seems unlikely. Much will depend on how the news media conduct themselves in the next year or two, and which party, or coalition of parties, forms the next UK government.