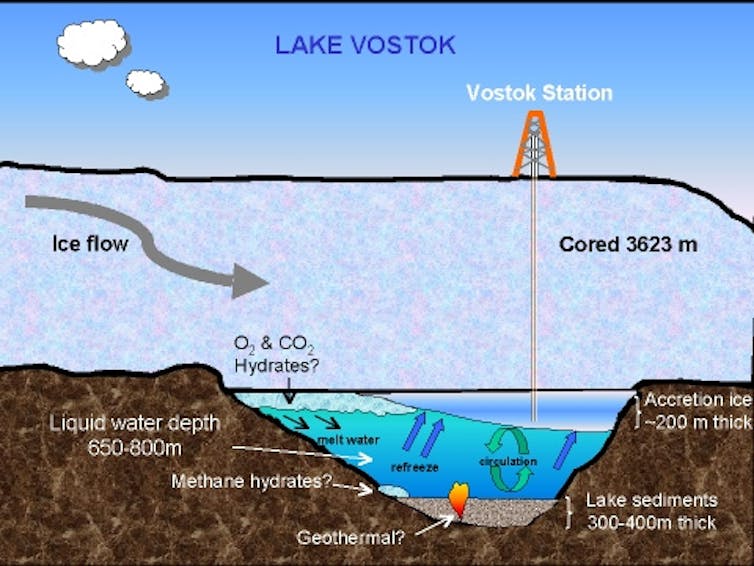

Late last week the Russian Arctic and Antarctic Research Institute (AARI) announced they had successfully drilled into the elusive sub-glacial Lake Vostok, a body of water lying under nearly 4km of Antarctic ice. The breakthrough is the result of 20 years of drilling at one of the most inhospitable places on Earth.

Much of the interest in the 15,000 square-kilometre Lake Vostok revolves around the fact any micro-organisms within it have been isolated for anywhere up to 30 million years, trapped in an environment similar to that of the moons of Jupiter.

So what does a sub-glacial lake in Antarctica have in common with the alien moons of Jupiter? And what’s the significance of the Lake Vostok exploration when we consider the search for extra-terrestrial life?

Every time astronomers look at Jupiter with a different instrument they seem to discover a couple more moons. When I was a child I learned there were 16 moons – now there are 66 and I’m only 28. But it’s the four largest of these moons that have attracted the most scientific attention.

They are now known as the Galilean moons, as they were discovered by Galileo Galilei when he pointed his telescope toward Jupiter in 1610.

The moons are named, poetically enough, after the lovers of Zeus (the Greek equivalent to Jupiter): Io, Europa, Callisto and Ganymede.

Most of what we know about the Galilean moons comes from an extremely successful NASA spacecraft.

The unmanned Galileo spacecraft was launched in October 1989 and completed an eight-year tour of Jupiter and its moons. That mission yielded images of the surfaces of the Galilean moons and spectral data showing the chemistry of their surfaces.

Among the many discoveries made by Galileo were the sulphur volcanoes of Io and a greater knowledge of Jupiter’s massive magnetic field.

Though Io is a sulphurous, inhospitable environment, the other three Galilean moons were found to have surfaces of water ice, with a number of other salty deposits.

Perhaps the most intriguing discovery was that under the icy crust of Europa lies what is thought to be a planet-wide ocean.

This was detected because the salts in this ocean caused a change in the magnetic field of Jupiter as the icy moon moved through the field. Discovery of this ocean under 6-100km of ice highlighted the potential of a warm and mineral-rich playground – a viable place for life to flourish.

This was deemed so important that, at the end of its scientific life, the Galileo spacecraft was plunged into the clouds of Jupiter, to avoid the possibility of the craft hitting and contaminating the pristine environment of Europa.

The issue of contamination is chief on the minds of many scientists as drilling equipment plunges into Lake Vostok.

In the lead-up to the breakthrough, some scientists were concerned that liquid being used to stop the borehole from freezing over – a mixture of kerosene and other hydrocarbons – would leak into and contaminate the lake.

The Russian scientists have refuted such claims and the Antarctic Treaty Secretariat has since ratified the drilling methods as well.

Discovering life in Lake Vostok would be a major scientific discovery. For a start, any organisms that live in the lake would have been trapped under the ice for millions of years. Such a discovery would also have significant ramifications for our understanding of the sub-surface ocean of Europa.

Any micro-organisms surviving in Lake Vostok could be an unknown form of life and an excellent candidate for life on Europa. The technology developed for the Antarctica project could be used to build a follow-up to the Galileo spacecraft – a craft that could land on Europa and burrow into the ocean.

Sure, a mission of this sort might still be many years away, but we are definitely heading in the right direction.

In the meantime, we’ll await the results of the Russian drilling expedition and look forward to December when a UK-lead team starts to drill toward Lake Ellsworth – a similarly buried Antarctic lake.

The UK team will be using a newly developed method of “hot-water” drilling, avoiding the use of kerosene completely and allowing for clean samples to be plucked throughout the drilling.

Stay tuned.