Stronger measures to protect lions in Africa from commercial trade failed to pass at the recent meeting of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) in Johannesburg.

CITES is a treaty between 183 national governments, known as the Parties, to control international trade in live wildlife and their parts. In a vote to up-list the lion from Appendix II to Appendix I – the highest category covering species threatened with extinction, in which trade is permitted only in exceptional circumstances – the Parties to CITES (CoP17) rejected a proposal from nine African nations to upgrade the status of lions.

At first glance, the decision is alarming and disappointing. The lion has undergone widespread decline in Africa, mainly from habitat loss, illegal trade in bush meat and retaliatory killing by people protecting their livestock. Although the species is not in immediate danger of extinction and trade is not the primary driver of declines, upgrading some lion populations to Appendix I was warranted.

Sadly, all indications are that lions will continue to decline in a significant proportion of their range, and increasing demand for their parts will likely fuel those declines. But had the parties voted “yes”, would it have helped?

Trophy hunting and the bone trade

Strengthening the ban would not have eliminated one of the main targets of up-listing proponents, the trade in lion trophies from sport hunting. Legal trade in hunting trophies is readily accommodated by CITES, regardless of the Appendix on which a species is listed. For example, the cheetah and leopard are both included on Appendix I, yet exports of trophies are permitted by a number of countries.

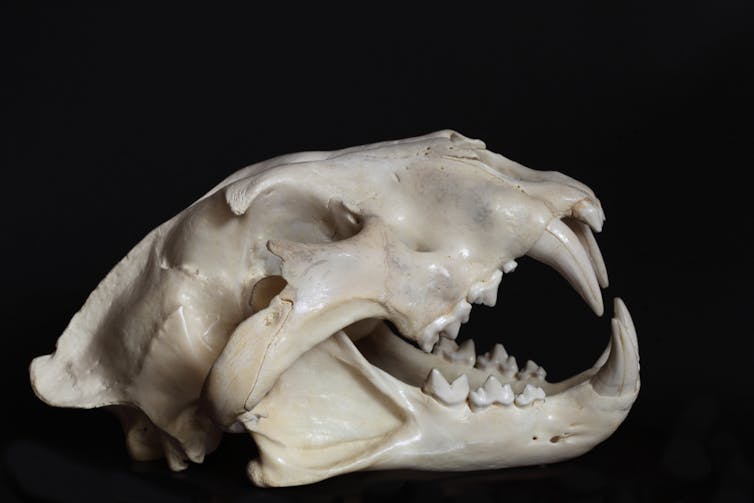

Nor would an Appendix I listing preclude trade in captive-born lions or their parts. So an upgrade would not necessarily have affected South Africa’s ongoing trade of lion bones scavenged from canned hunts of captive-bred lions. Full skeletons – minus the skull, which the hunter usually keeps – are legally sold to Lao People’s Democratic Republic, China and other Asian nations that value big cat parts for “medicinal” uses. This takes place despite the complete absence of evidence demonstrating any therapeutic value.

One step forwards, two backwards?

This is not to say that CITES was unable to address some serious issues that affect lion conservation. CoP17 adopted a new resolution to ban all trade in wild lion parts; specifically bones, bone pieces, bone products, claws, skeletons, skulls and teeth removed from the wild and traded for commercial purposes. This is welcome news.

Unfortunately though, the loophole that perpetuates South Africa’s lion farming industry has been left open. As seen from failed experiments allowing legal ivory sales, legalised trade may fuel demand and creates pathways to sell the products from illegally killed wildlife.

The legal trade in bones from captive-bred lions perpetuates the demand for big cat parts - not only of lions but also of leopards, jaguars and highly endangered tigers. These bones are largely indistinguishable except to experts. Deciding what is lion or tiger, and legal versus illegal, presents a formidable challenge for local authorities in Africa and Asia.

The Parties to CITES should be congratulated for recognising that trade in wild lions needs to be addressed. But I fear that, in failing to take on the captive bone trade, their efforts will be undermined. As long as South Africa continues to trade in body parts from farmed lions, an escalation in wild African cats being killed for the same markets in Asia is inevitable.