Mexican director Alfonso Cuarón’s masterpiece Roma was greeted with critical acclaim and three Oscars at the 2019 Academy Awards. But, even as Cuarón was basking in the spotlight, he was outraged at the way Netflix had decided to subtitle the film for Spaniards.

The movie was shot using Mexican Spanish and Mixtec, a language spoken by about half a million people in the Mexican states of Oaxaca, Puebla and Guerrero, and in California in the USA. Netflix decided to give the Mexican Spanish and Mixtec dialogue subtitles in Iberian Spanish for its audience in Spain.

Cuarón considered this decision to be “parochial, ignorant and offensive to Spaniards themselves”. According to him, the Spanish audience was capable of connecting with the film without subtitles. As Mexican author Jordi Soler told the New York Times:

It’s like if you have an American film showing in the UK and the character says he’s going to the washroom, but the subtitles say he’s going to the loo. It’s ridiculous. They’re treating the people of Spain like they’re idiots.

Reactions from viewers, writers and translators on social media denounced Netflix’s decision as paternalistic and highlighted its colonial connotations. The media, both in English and Spanish followed the discussion closely. Ultimately, Netflix removed the subtitles.

The world used to be divided between those countries using subtitles (including, in Europe, the Scandinavian countries, Portugal, Greece), and those opting for dubbed versions (France, Italy, Spain, Germany). In Latin America, it tended to be the medium that dictated the type of translation: subtitles were popular at the cinema and on cable TV, while dubbed versions reigned on public and free-to-air television.

These days the situation tends to be more fluid. My research has shown that even in countries that have traditionally dubbed movies, some viewers prefer subtitles. Subtitles are faster to produce than dubbed versions – and users claim they give a viewing experience that is closer to the original because they maintain the original actors’ voices.

Subtitle boom

The function of subtitles is also changing, depending on where you are. In the UK, for example, subtitles have traditionally been aimed at deaf and hard of hearing viewers and viewers of foreign language cinema. But subtitles are now also becoming popular among the wider TV audience.

Subtitles are being used by viewers as a way to stay focused on the content and to watch videos on their smartphones and tablets while commuting or in busy or loud places. Viewers also use subtitles to improve their language skills, as my research on the use of subtitles in Netflix’s House of Cards has shown.

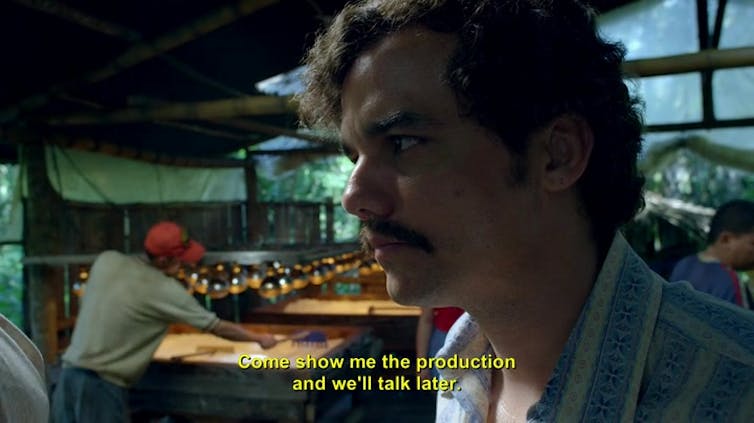

Subtitles are being used in multilingual storytelling. Netflix’s Narcos was shot in both Spanish and English which was seen as a clever move for a distributor looking to expand its audience into lucrative new markets.

Dub-style

But since 2015, pay-TV television channels in Latin America, such as Warner Channel and Canal Sony, have decided to switch from subtitling to dubbing for US television series and films. Warner Channel argued that the decision was in line with industry trends and suited the younger audience’s tendency to multitask while watching TV. While not everyone seemed to be happy at the time, dubbing has become standard for these channels.

Netflix, meanwhile, claims to have “brought back the lost art of dubbing” for the English speaking audience. The distributor offers its content subtitled and dubbed into different languages – 27, for the recent Chilling Adventures of Sabrina, according to vice-president of product, Todd Nellin. “If you want to watch Ghoul, you can watch it dubbed into English, watch it in Hindi with English subtitles or dubbed into English with English subtitles,” Nellin told Forbes magazine in 2018.

The distributor is also taking pains to make dubbed versions sound more natural and less “dubby”, hiring directors and specialist actors to make dubbed versions of films less like a new recording and more like a new production.

Stop making sense

So distributors such as Netflix are attuned to the benefits of providing flexibility to increase the appeal of their product to different people in different countries speaking different languages. This is a positive trend – up to a point. But translation is not neutral; translation decisions carry ideological and social consequences.

In June 2019, Netflix re-released the cult classic anime Neon Genesis Evangelion, with new English translations for subtitling and dubbing and a new voice cast. The launch was hugely anticipated – but the new translation was greeted with a heavy backlash on social media from hardcore fans.

Fans baulked at the way some key themes appeared to have been altered. The most contested change involved an exchange between two characters that radically changes a relationship that has been understood as queer.

The Neon Genesis Evangelion controversy shows the complexities of translation. It is a good example of how translators need to find solutions between their commitment to the source product and the audience’s expectations. It’s not just a matter of offering subtitles, but providing viewers with quality subtitles that facilitate their social integration. This is something that YouTube needs to consider when using AI to subtitle the videos it hosts.

All the different forms of translation available offer opportunities to increase accessibility and support integration. The efforts by distributors to provide multiple options for viewers, besides making commercial sense, are a positive move both socially and culturally. But sensitivity, rather than purely commercial reasons, must be at the heart of the process. Otherwise all their efforts risk getting lost in translation.