Even for a relatively seasoned observer of the antics of government, the recent performance over fracking, crowned by the prime minister’s comments about fracking his backyard, has been a wonder to behold.

The government has been at pains over the past decade to put in place an energy policy on three legs: decarbonisation of the energy sector in order to meet the emission reduction targets enshrined in law by the Climate Change Act 2008; energy security, to reduce UK dependence on imported fossil fuels and their volatile prices; and affordability, to meet the first two objectives without affecting the competitiveness of UK business or driving low-income households into fuel poverty. In just two weeks this painstakingly crafted strategy has been torn up in the dash to frack.

The best possible outcome from this is that Britain will benefit from large quantities of shale gas (without adverse effects on the local environment), and that this will drive down the price of gas. No one seems to consider for a moment that this abrupt shift away from low carbon energy will do anything but increase carbon emissions and cause the UK to miss its targets.

There are two reasons for this. First, if the UK produces more gas it seems highly probable it will use more of it, and gas is the most carbon-rich fuel the UK will use in any quantity after 2020, having already substituted it for most of the coal-fired power plants.

Second, low carbon investors – Siemens, Mitsubishi and others – will be scared away from investing in developing the UK’s offshore wind industry. There is ample evidence that they were intending to invest, but it makes little sense to build wind turbine factories to supply a growing market to 2020 if that market will collapse thereafter. This is what they will judge to be the likely outcome from this outbreak of gas-mania, and the refusal to commit to a 2030 target for renewables. Under these circumstances it makes more sense to service the UK market from abroad - wave goodbye to the manufacturing supply chains that could have regenerated much of Britain’s east coast, from Aberdeen to Yarmouth.

However, there is no one outside the small circle of government fracking enthusiasts (and the industry) who believes that the best case outcome will actually be achieved. They stress that the UK is not the US: the geology is different, the gas resource is different, the technology and extraction process is likely to be more expensive, and the population density will make it more difficult to sink the requisite number of wells.

They estimate it is very unlikely that the amount of shale gas extracted will be sufficient to reduce the European price of gas, and that if this price is instead reduced by the gas glut in the US, the higher cost of UK shale gas may render it altogether uneconomic. If they are right, the dash to frack could leave the UK more exposed to high and volatile prices of international gas markets, and consequently greater insecurity, than the country currently faces - all three legs of the government’s energy policy of recent years swept out from underneath it. These voices – many of which may also be heard in government – urge caution in betting the farm on this particular prospect.

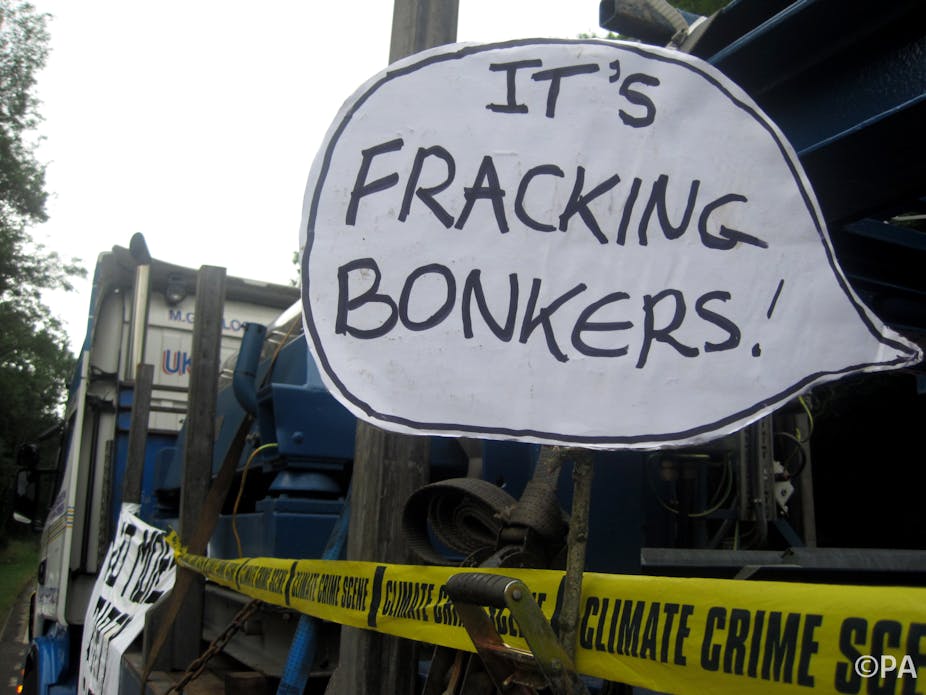

But on rush the frackers, into the valley of Balcombe. Any chance this industry might have been developed with community consent into a nice little earner over a reasonable time, generating foreign exchange for the country and satisfying some of the demand for natural gas we will undoubtedly need through to 2040 – this chance has been recklessly imperilled, quite needlessly, by the confrontational, now-or-never strategy which can be seen unfolding.

The strategy is quite unnecessary because the gas is not going to go away. Nor is the technology. Nor is the global demand for gas. What does seem likely to have been lost irrevocably is the chance to develop it without a massive police presence driving it through the protests of locals and those set on meeting carbon targets.

Is this madness – or is there method in it? Perhaps a means to destroy the Climate Change Act by changing the situation on the ground that make its targets untenable? Perhaps confirmation of the lobbying power of a fossil fuel industry desperate to claw its way back into the pole position of primary energy provider that for a few years it has seemed like losing?

These questions are still open. If the dash to frack continues, the option of a low carbon future for the UK will not be.