Privacy – in our bedrooms, at work, on the street and on the internet – is important to everyone. But every week brings another story demonstrating the ongoing shredding of privacy that undermines those chances. Maybe it’s time we gave up trying to avoid surveillance and started thinking about how to make it work for us.

It’s not just the corporate and governmental surveillance machines that suck up our data. It’s not just that we continually, voluntarily, trade our privacy away for convenience on Facebook, on Google, in our browsers, in our phones. It’s that the continual drip of new ideas makes destroying privacy ever easier and preserving it ever harder.

Recently we’ve found out that websites can track our identities by minute flaws in our phones’ accelerometers. Before that, we learned data from Netflix could be easily de-anonymised and that your identity could be revealed just by looking at a small selection of your movie choices. The trend is unrelenting: the tiniest speck of information is enough for powerful organisations to blow your privacy wide open. Even cyber-criminals are finding it impossible to maintain their privacy online, so what hope is there for the rest of us?

The one-way mirror

Want to know exactly what Facebook is doing with your data, how potential employers track your life or how the NSA is using the information in your emails? Well, sorry, you can’t. It’s proprietary, private information that is legally protected. Privacy laws have never protected us from being spied upon – but they’ve been pretty effective at preventing us from finding out who’s doing the spying.

There is a more important challenge on offer though. If we can’t stop governments from spying, as they’ve always done, we should focus on the important task of preventing them from abusing the information they’ll inevitably gather. If the ultimate goal of maintaining our privacy is off the table, we should pursue other options.

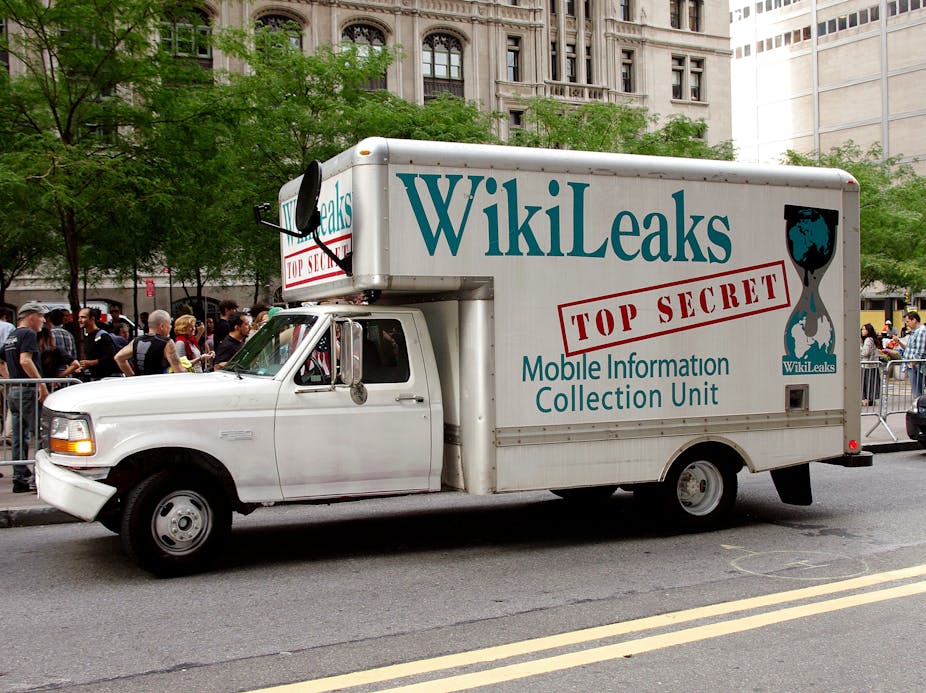

It might be that the second-best solution is to embrace the change and demand the best out of it that we possibly can. For a start, we can demand the democratisation of mass surveillance. We could have a universal culture of transparency in which the powerful submit to “sousveillance” by everyone else from below. The lives of politicians, business leaders and civil servants should be as open to us as our lives currently are to them.

Making surveillance work for us

Immediate total transparency seems utopian. Aren’t there secrets that genuinely need to remain hidden? Of course there are, but not nearly as many as large organisations claim.

Increased surveillance allows for increased transparency. It would be unconscionable, right now, to publish detailed plans for building hydrogen bombs. But if instead every gram of nuclear material were tracked and controlled, we wouldn’t need to rely on secrecy for security. Apart from a few genuine information hazards – the precise DNA sequences of certain pathogens, for instance – we could cope with a lot more transparency than we’ve been led to believe. And the more intrusive, invasive and all-seeing the security state becomes, the less the need for any secrecy at any level.

There are other ways that mass surveillance would transform our society, some good, some bad, some inevitable. Governments will certainly use mass surveillance to combat crime, with increasing effectiveness as cameras get ubiquitous and artificial intelligence takes over in analysing the data.

But we will have to make a concerted effort to win other changes. We should insist on a radical cut in police numbers and powers, for example. The police currently have immense power, which allows them to harass, arrest, or act against citizens in ways that would be huge violations of rights if anyone else did it.

These powers are needed today, since the police have to investigate crimes, interrogate suspects and don’t know who in any given crowd is carrying a weapon. But with surveillance taking over the bulk of the police work, there would be no need for these powers to remain. The police could be reduced to a small rump, tasked mainly with analysing the data flagged by artificial intelligence, and then arresting the specific person who has committed a crime.

It’s a general pattern: in many areas, surveillance can substitute for other, more egregious uses of state power.

Living in a transparent world

The system would also work across borders. Nations that hate each other would at least be able to trust each other. They could agree to fully verified treaties and safely reduce their armies. This would allow them to avoid any Cold-War-style near misses, which are, after all, often caused by uncertainty as to what the other side is up to.

On a smaller scale, businesses would be more comfortable doing deals with each other and individuals would be able to trust complete strangers in times of need: someone will be watching them, logging their reputation, keeping them to their word. Freely available long-term surveillance recordings will help those abused at work or in the home, unable to currently complain. The recordings will be waiting, ready to be used against the abusers at any later date.

This just scratches the surface of all the good we can demand from mass surveillance; additional ideas abound. Pandemics could be prevented or at least preempted by carefully tracking the progress of a disease, informing those that get infected, and implementing local and targeted measures.

Other risks, large and small, could all be reduced: how much good would the emergency services be able to do if they had access to the precise locations and identities of everyone in a city at the moment an earthquake struck? We could empty security queues at airports and even obviate the need for passwords. We could open new avenues for medical and social research with the vast amount of information that could be put at our disposal. The potential positive applications of mass surveillance are innumerable.

The fight for good mass surveillance is a fight worth having, instead of a doomed rear-guard action on the lost battlefield of privacy.