The world’s a mess. How do thoughtful people make sense of it all? In this series we’ve asked a number of our authors to suggest a book, philosopher, work of art – or anything else, for that matter – that will help to make sense of it all.

There was a time when I thought I had pretty good concentration. That time is gone. Sucked into a vortex of addictive news checking, Twitter feeding, I keep on updating, streaming, screaming, plugged into yet more “news from nowhere”. Angry old white men, angry young white men, forests up in flames, towns dragged down in mud, turtles wrapped up in plastic. I need an “out”.

Flying around Europe for work (EU funded, so yes, Brexit kills me) I find myself playing the same song over and over again. It’s my way not of “making sense” of what seems mostly to be nonsense, but of finding an outlet – one that creates its own different, poetic world.

Every time the plane takes off I play “Jubilee Street”, a song by Australian rock musician Nick Cave – over and over again.

And it’s not only my takeoff soundtrack. I play it when I need to be somewhere else, where not making sense has its own beauty and internally coherent narrative. I need to hear a Nick Cave story and out of all of them, from all his time in music, “Jubilee Street” is the “magic one”.

I have been listening, on and off, to Cave ever since he screamed “Hands up Who wants to Die” on “Sonny’s Burning” with his band The Birthday Party in 1983. I 5fell out of love with him for some time but there he was, always making music. There were side projects with singers Kylie Minogue and PJ Harvey, there was the band Grinderman, his porn alter ego, and there were film scores.

All the time, along with Warren Ellis, his close musical collaborator, multi-instrumentalist, friend and fiendish violinist, he has been concocting stories about love, death, violence and sex. No one sounds like him. No bands plough his furrow. His world is indebted to the Western, the Gothic, to the Grand Guignol (The Theatre of the Great Puppet).

His music is the sonic equivalent of David Lynch’s films Wild at Heart or Blue Velvet, like German film director Werner Herzog’s Nosferatu the Vampyre. It sounds odd to say that it functions as an escape, but Cave’s world has always been the same, existing in a parallel space to the “real” world.

Love and loss

“Jubilee Street” is, like a lot of Cave’s work, a tale of love and loss. It recalls a woman called “Bee” who lives on the titular street making “ends meet”. She has a “little black book” wherein the protagonist finds his name written, “on every page”.

Bee is a working girl. Beyond that, the narrative becomes surreal and Cave starts to spin his web. Images that are not possible in this world become imaginable within his; if you suspend disbelief, you travel with him as he sings this song.

He carries strange things on chains and leashes, pushes impossible objects up hills, for some reason “the Russians” move into Bee’s place when it closes down, and all the while the song builds and builds to its climax where Cave sings about transforming, about flying. He marvels:

Look at me now!

What he might have turned into, who knows? He laments how he is “out of place and time”, and “over the hill” and out of his mind. This confession of insanity and ageing, the feeling that he doesn’t belong, that he is out of kilter with the world. It’s one that makes no sense to him since Bee left – it is one that is confusing but tantalising, kaleidoscopic in its imagery. It’s the tale of a lost man who somehow finds beauty in his predicament. And this is why I guess it makes sense now.

The track comes from the 2013 album Push The Sky Away and was recorded in the South of France, where a children’s choir sang the backing vocals. Its hook, 18 notes that emerge early on in the song, is played on violin and echoes later in the children’s voices.

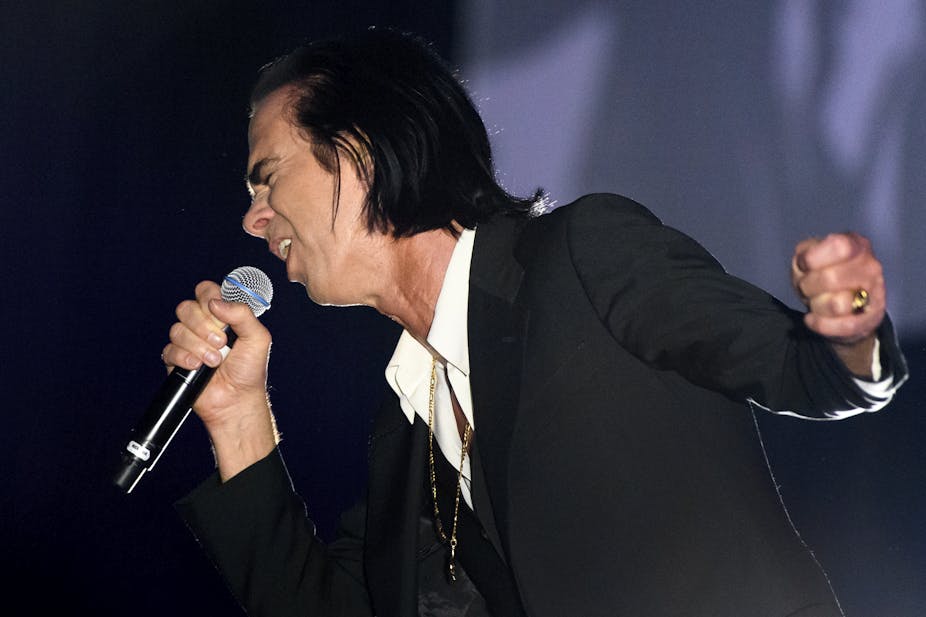

It is showcased at the end of the trailer for the film “20 000 days on this Earth” by Ian Forsyth and Jane Pollard, which depicts Cave in a gold lamé shirt performing at Sydney Opera House in 2014, arms out, crucifixial, shamanic. And so he acts out, in song and on stage, this ability to transform, to change, to become the butterfly, to soar into beauty.

Compelling cinematic images

Cave has experienced family tragedy, losing one of his twin sons at 15. He has courted political and peer disapproval by performing in Israel. But his life and political decisions are not what draws me to him – far from it. It’s his work, his conjured up worlds, that create compelling cinematic images I want to visit again and again.

Try “Stagger Lee” and you will be transported to a mid-century, mid-Western town where the outlaws rule. Listen to “Nature Boy” and you will marvel at a relationship where the guy dresses up in a deep-sea diving suit for erotic charge. Listen to “Into my Arms” for a love song, “Red Right Hand” for a murderer’s confession, or “Loverman” for some deranged sex.

“Higgs Bosun Blues” sees Cave “driving down to Geneva”, boasts a cast of pop star Miley Cyrus and bluesman Robert Johnson, and includes an edict to bury him with his yellow, patent leather shoes should he die. But first, try “Jubilee Street” because of its creeping, haunting beauty. Cave finds poetry in the darkness. That’s why I keep listening to him.