Politics, Independence and the National Interest: the legacy of power and how to achieve a peaceful Western Pacific

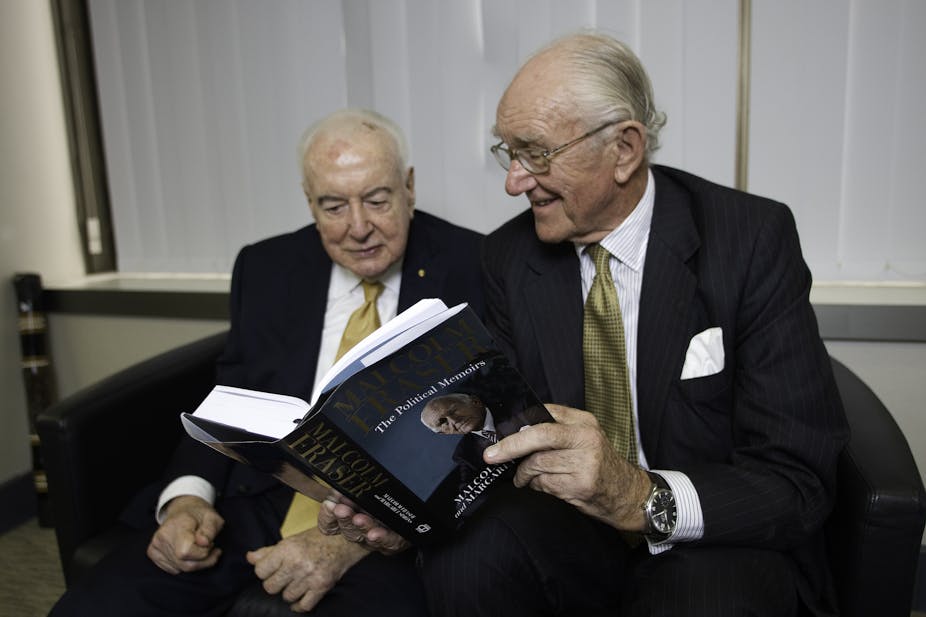

I am honoured to be asked to make this speech. During the turbulent years of the 1970s, few people would have believed that Malcolm Fraser would be delivering a Gough Whitlam Oration. Politics is a hard business. The opposition of one party to another can become toxic. We have had this demonstrated to us all too often in recent years. But it does not always have to be this way.

By any standards Gough Whitlam is a formidable, political warrior. He has inspired an undying loyalty amongst his supporters. He is an historic figure who has made a significant impact on the life of Australia. He had grand ideas, many of which left their mark on Australia. A number of which were embraced by the following government. Others have survived despite the opposition from the other side of politics.

He was the first Australian Prime Minister to recognise China. As Australian Prime Minister he had the confidence and knowledge to recognise the distinct national interests of our country. He established ground breaking enquiries into Land Rights for Aboriginal Australians and also over a number of environmental issues, where reports were later implemented by my government.

As political antagonists we had substantial differences, but as Australians we had shared interests and concerns.

This is not the place to traverse the politics of the middle 1970s. I doubt very much if Gough Whitlam has changed his view of those times.

For my own part if I were confronted with the same issues, the same circumstances, I would still go down the same path.

But distance does also give a sense of perspective.

In the middle 1970s we were told the supply crisis was more grave than any other that beset Australian democracy. That the divisions would be permanent.

The conflicts of 1975 were intense, but the passions have dissipated.

I believe there are many Australians who welcome the fact that the two chief protagonists in the political battles of those times have established a good relationship, a friendship and respect for many of the things for which we both stand.

I believe we have recognised that those policies and attitudes, on which we have, if not a common but a shared view, are more important than the issues that divided us.

The Whitlam Labor Government ended the final legal remnants of the White Australia Policy. The symbolism of this has been fundamental. It terminated a policy that had been eroded over the post-war years. One significant act with later implications for the White Australia Policy was taken in 1954 when Menzies signed on to the Refugee Convention. In March 1966, Hubert Opperman as Minister for Immigration, made a speech which effectively nullified the practical impact of the White Australia Policy. Anyone who reads that speech will see that it is couched in guarded terms. It was the Whitlam Government who crossed the symbolic bridge of publicly ending the White Australia Policy.

The great post-war immigration was a major step on the road to a multiracial Australia. Initially it was racially based. Arthur Calwell reflected a political consensus when he said that he wanted the great majority of migrants to come from Britain. That desire was never realised.

Political and economic refugees, in their tens of thousands, sought to flee Europe. The political parties of that time recognised that an Australia of 7 million people was not defensible. Our nation had to build, to invest and grow as rapidly as our resources would allow. This meant a migration program that would come from many countries other than Britain.

When we began our major immigration policy we were very largely an Anglo-Saxon Irish community, a narrow and somewhat bigoted country. That had to be set aside. But in reality it would have been very easy to arouse the racism or exacerbate sectarian feelings which were still strong. The immigration program needed bipartisan support. It achieved that bipartisanship.

Both Government and Opposition knew that Australia was embarking on a great adventure in nation building. If there were problems between new citizens, both sides worked to overcome those problems and to maintain harmony. It was recognised that no one should play politics by seeking to exploit racial or sectarian divisions. Indeed the parties worked hard to bury remnants of the bitter sectarianism exacerbated so wrongly by Prime Minister Billy Hughes. Both sides recognised their duty to the nation and the seriousness of the task ahead of them.

It is not surprising that the Federal Parliament acted in these ways. Many of the Members and Senators had experienced service in two World Wars. All had experienced the hardship of The Great Depression. For some Australians the first job they had was when they joined the army and went to the Middle East. Many on both sides had been prisoners of war. These members of the Australian Parliament knew that the democracies had to govern themselves better, that they had to put differences, even hatreds aside and seek to build a future in which humankind could survive and prosper.

The political leaders of those days knew and understood these realities. Civilisation had nearly destroyed itself. Leaders of countries across the world, both victors and vanquished, knew that the international community had to cooperate and build a productive and peaceful world.

On the question of migration the Parliament had maintained a bipartisan attitude since the end of the second war. In the middle 1970’s this was sustained despite the sharpness of the divisions on economic management, constitutional matters and issues of due process.

At the end of the Vietnam War, tens upon tens of thousands of Indo-Chinese sought to flee to safety. Initially the Whitlam Government decision was to have limited numbers of people from Vietnam. My Government made the decision to take large numbers of people. Gough Whitlam did not play politics with this. It would have been easy to do. Instead he led his party to fully accept the convention of the post-war years. Bipartisanship on issues of immigration was maintained. This bipartisanship was fundamentally important. It shows that political conflict can live alongside the sustaining of a shared, deep respect for people regardless of colour, race or religion, a belief that people should be respected for who they are. The capacity to engage in conflict and maintain such a respect depends on a degree of consensus between political leaders. Gough Whitlam and I participated in this consensus.

If instead of this consensus, the disgraceful race to the bottom of the populist political point scoring of recent years had prevailed, the cost to Australia would have been enormous.

Australia would have lost tens upon tens of thousands of hard working productive citizens. Citizens who have manifested an extraordinarily strong loyalty to this country. Citizens who have directly sought to repay what they regard as the generosity of their reception in Australia. Some have entered the armed forces, others have entered public life. We would have lost all of this and we would have re-established our reputation as a racially exclusive society.

Recent years have shown that progress in dealing with racism is not guaranteed. We should not lose heart. The possibility of regression has always been present but actually progress has prevailed overwhelmingly amongst the people of Australia.

By the middle 1970s the political parties were opposed to apartheid but there was still contention in the party room. There was still robust resistance. Opposition to apartheid was not universal. I can remember a party room discussion quite early in the time of my Government. The question of apartheid was listed on the agenda. It was clear that a few who supported the Afrikaners had organised themselves to speak one after another. The gist of their remarks were, “Why aren’t we supporting our white cousins in South Africa?” “Why are we supporting the ANC, a communist organisation, a group of terrorists?” That debate ended somewhat abruptly after I advised my colleagues of the realities of the Fraser Government. If they wanted an Australian Government that would support a small white minority in South Africa determined to keep the overwhelming black majority in a state of perpetual subjection, they would have to get another government.

The Whitlam Government believed Australian Aboriginals should have land rights. An enquiry was established. The Government did not last long enough to implement the recommendations of the Woodward Commission. Nonetheless, my Government legislated the Aboriginal Land Rights in 1976. Land Rights for Australia’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders was established in part as a result of a commitment shared by successive governments.

Land Rights stems from an attitude about people. The need to deal with people on the basis of respect, a recognition of what people are, of their history and of their culture.

Land Rights comes from an idea of what Australia can and should be.

This idea of what Australia can and should be underlaid the Galbally Report. The Galbally report sought to give substance to the reality of multiculturalism and the establishment of SBS. The report and the actions taken as a result of that report were designed to fulfil the idea of respect for all people, no matter whence they came. This value is fundamental to a good Australia.

It is a value which both Gough Whitlam and I advanced.

Australia has gained great strength by our tolerance, by our diversity and by our respect for the history and culture of people whose pasts are different.

Over the years there have been a number of issues over which Gough and I came to have a relatively common view. From the back of a truck overlooking Fitzroy Gardens we both spoke for the independence of The Age and of Fairfax and against its control by foreign interests. We believed then, that it does matter who owns major newspapers, significant instruments for propaganda and information. Proprietors seek to influence their readership. If their primary interests are foreign to Australia their interests are not necessarily ours. Gough and I can remember in November 1951 Menzies, who on some things was far ahead of his time, intervened when a British company was seeking to take over four significant radio stations. He came into the Parliament and said it would be wrong for people who do not belong to this country to own such a powerful medium for propaganda. A neat way of putting it without offending the British. The takeover attempt was dead. How the world has changed. Today’s political parties seem not to mind who owns the print media. In our time there were six or seven proprietors, now there is one and a half.

Increasingly those with financial resources come to have a disproportionate influence on public affairs, an influence magnified by the activities of lobbyists whose impact on public affairs is not benign. We have seen how in relation to the mining industry, three enormously wealthy individuals have sought to exercise political power, totally disproportionate to the merit of their argument.

Today money has too great an influence on the policies of political parties. If countries such as Australia wish to maintain the effectiveness of their own democracy, we will need to look much more closely at the power of money and how to limit the political influence of those with great financial resources.

I want now to turn to other issues which are critical to Australia and indeed to our whole region. How can we best contribute to peace, to progress, to stability in the Western Pacific and South-East Asia? I believe that Australia today should be able to have more influence than the Australia of 50 years ago.

Two matters have arisen which cast doubt upon that and which cause many throughout South East Asia and indeed many in Australia itself, to question our influence and indeed our purpose.

Before Tampa there would have been many who accepted that the idea of the White Australia Policy was dead and that those who supported racism had no influence. Since Tampa, despite the great and beneficial diversity of people within Australia today, there are many who interpret our attitude to refugees, and the toxic and demeaning debates that have taken place over this question, as a resurgence of racism.

Our treatment of refugees, and the poisonous debate engaged in by our major political parties has done Australia much harm throughout our region.

There is another issue of complexity and difficulty that we need to address - the nature of our relationship with America.

In the past twenty years, we seem more and more than ever to be locked into the United States’ purposes and objectives. ANZUS was invoked to support America during the invasion of Iraq. The war in Afghanistan was originally sanctioned by the United Nations. It was for a specific purpose to destroy Al Qaeda and Osama Bin Laden. It then morphed into an attempt to establish some kind of democracy in Afghanistan itself. That had not been sanctioned in the same way by the United Nations. Why did we follow America without question when so many believed this change in mission was impossible to fulfil?

Did we really believe that by force of arms we can force a system of government on people whose history and culture are so very different? We should have withdrawn from Afghanistan when the nature of the mission changed.

America had a huge army in Vietnam and was not able to win. In Iraq, the government arrested 300 or 400 hundred political opponents almost in the same week that President Obama brought the last troops home and suggested that the job had been successfully completed. There are bombings in Iraq almost every week and scores of people are killed. Security is limited and there are grave doubts about the future.

Vietnam, Iraq and Afghanistan should give pause to those who believe that there can be military solutions to problems of governance in other countries.

We need our military, a military efficient, operating and effective. When our military goes to war it should be for purposes and objectives clearly in Australia’s interests, not merely because the Americans want some company.

There are too many who believe if we support the United States and go to war when they want us to, they will in turn support us on issues that we regard as fundamental to our own security.

History strongly suggests that the real determinant of the actions of great powers are their own interests. We should not expect anything else.

The British Empire once existed, Australia was part of it. I remember being shown a map of the world coloured pink. We would be told that where the map was pink you would be safe because that was part of the British Empire. But, when Australia was very much under threat, when Darwin was being attacked, when Japan was advancing, Britain was so beleaguered that helping Australia was not possible. Strong arguments can be made that Churchill used every device, every mechanism, every lever of power and influence to secure Britain, no matter what the consequences to a country like Australia. That was his job and without Churchill, Britain and the free world may not have survived.

The point remains however, that too much reliance on great powers for one’s security is not wise.

Once it became clear that Britain could not help us, we transferred our sense of dependence, which had dogged Australia since Federation, from Britain to the United States. That sense of dependence remains. Today I believe we should be old enough and mature enough to grow out of it.

I support ANZUS and the American alliance. At the same time my belief in its efficacy has its limits. Our own skill, our own strength, our own diplomacy, wisdom, our contribution to our region, our contribution to the overall security of that region - these are what will secure Australia’s future.

We need to be a nation acting independently with a mind and direction of our own and we need to be recognised as such.

This does not mean we cannot have alliances. There are many things in which we will always agree with the United States, but there are some very important things in which the Australian interest is quite different from theirs.

The United States’ major interests are in the western hemisphere. Our major interests are in the East and South-East Asia. Our future is totally bound with that of the Western Pacific, East and South-East Asia. That geographic difference defines in significant ways our different national interest. We live in the Western Pacific, our secure and peaceful future depends upon our relationships with countries of the region. We do not have the luxury, as the United States does, of being able to withdraw across the Pacific, to the western hemisphere.

We must rely more on ourselves. We need to recognise that ANZUS itself is a strictly limited treaty. It is limited geographically and substantively. It involves a commitment in the first instance to consult. Then according to their constitutional processes the United States may or may not provide military support. There is no blank cheque, no automatic provision of military support. The hard commitment does not go beyond consultation.

That is quite unlike NATO which contains an automatic commitment to defend. The difference between the treaties is remarkable.

There have been a number of occasions when the United States has not supported an Australian view when we had felt our particular interests were affected. During the period of confrontation the London Economist had this to say “No Indonesian regime short of a blatantly communist one would earn active American hostility, no matter what harm it did to the national Australian interests”.

To point this out is not an anti-American statement. It is a statement of fact. If we blind ourselves to these realities we blind ourselves to the necessities for our own survival. The United States remains enormously important. On some counts it remains the world’s best hope for a peaceful and secure world. Many of the good things that have happened since the Second World War, the United Nations, the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, even the International Criminal Court, which they have not ratified, but whose statutes they helped draft, would not have been put in place without the United States’ leadership and support. Good things have happened because of leadership or support from America.

This does not mean that Australia can buy security by supporting America unconditionally. Unconditional support diminishes our influence throughout East and South-East Asia. It limits our capacity to act as an independent and confident nation. It limits our influence on the United States herself. The United States would expect an ally to have views and to put those views and help form policy.

I am reminded of some words of Abraham Lincoln:

I am not bound to win,

but I am bound to be true,

I am not bound to succeed,

but I am bound to live up to what light I have.

I must stand with anybody that stands right,

stand with him while he is right,

and part with him when he goes wrong.

I believe that in dealing with countries in our own region, we need to show a greater element of independence and a greater strength of mind.

We need to increase our sophistication in our approach to relationships throughout East and South-East Asia. For example our government still tends to say that strategic considerations have no impact on our good economic and trade relations with China. That is plainly not true. We cannot expect our trade relationship to be unaffected if on every occasion we follow America in strategic matters.

Independence of mind and recognition of Australia’s national interests will become more important in the light of developments in the relationship between China and the United States. If the United States wishes to maintain a position of primacy over all others, that will not be acceptable to China. No less, if China because of its increasing economic influence and growing military strength, seeks to replace the United States, that will not be acceptable to the United States.

There has been a recent conference in Singapore, the 11th International Institute for Strategic Studies Asia Security Summit. The most thoughtful, constructive and rational presentation by far was made by the Indonesian President Yudhoyono. By contrast the United States Secretary of Defense’s main thrust was the rebalancing of military forces into the Pacific. It was not a constructive speech because it shows quite clearly that the United States believes that the backdrop of military power is necessary for her to achieve the outcome that she wants. One could almost believe from that speech that the Secretary of Defense regarded the Western Pacific as a region to be controlled by the United States. The way Australia immediately rushed in, and once again tied herself to American coattails shows that the Australian Government does not understand how to secure peace.

The only solution that I can see of minimising the potential friction between these two major powers, is by cooperation. It is by partnership. It is if you like, by a concert of nations. This should contribute greatly to peace, security, progress throughout our entire region. A major part of Australian policy should be to work for such a result.

Such a result is well capable of achievement. A senior Chinese official said to me the other day, China does not want America to withdraw from the Western Pacific. China knows that her strength and increasing influence causes some concern amongst neighbouring countries, that concern would be all the greater if the United States withdrew. It is in China’s interests also for America to remain a country of influence. This suggests that a concert of nations, acting with due respect to all countries does hold promise.

Australia does need to play a part. If we have independence of mind, if we have confidence in ourselves, as indeed we should as an independent nation, we cannot just keep doing as we have in recent times, just doing what America wants. Troops in Darwin, military activities on Cocos Island, our following America into Iraq, staying in Afghanistan, all indicate an unthinking compliance with American policy.

If we continue on this path we will very soon find that we have made ourselves irrelevant to East and South-East Asia, politically and strategically. Irrelevant, because Australia will have nothing to contribute. Being and being seen to be independent and having a clear eyed view of what can achieve security and continued peace throughout this whole region is critical to Australia’s future.

The choice for Australia to make is not for China or for the United States, but independence of mind to break with subservience to the United States. Subservience has not and will not serve Australia’s interests. It is indeed dangerous to our future.

Australia should not do anything, for example, that suggests that we could be part of a policy of military containment of China, but marines in Darwin, spy planes in Cocos Island make us part of that policy of containment.

We would not be alone in opposing containment. At the InterAction Council meeting in Tianjin, China which I recently attended, with 20 countries represented, including a significant number from our own region, Singapore and South Korea included, endorsed a Communiqué which condemned containment. In his opening speech, former Prime Minister of Singapore, Goh Chok Tong had this to say “Any rhetoric of "containment” is dangerous. My view is that any attempt by the US to contain China will not work, nor will countries in the region want to take side on this.“ These are strong words for a Singaporean former Prime Minister. Singaporean Governments have normally avoided public criticism of the United States.

We should be trying to lead the United States away from containment.

It is not always understood as China understands very clearly, that the United States is running a two-track policy. When I was in Beijing recently, Secretary of State Hilary Clinton led a large, effective delegation to China for a 4th round of Strategic and Economic discussions. It appeared that those discussions went well. A number of continuing dialogues were established. We want consultation. We want mutual understanding. We want to resolve difficulties through diplomacy and dialogue. We want to understand each other better. That seemed to be the message coming both from China and the United States.

If that is the true American attitude, why does the United States talk of rebalancing military power to the Pacific? They already have massive power in the Pacific. More than all other nations combined. Do they really need more, for what purpose? What is the need to enhance naval cooperation with the Philippines and Singapore? What useful purpose do marines based in Darwin fulfil? What is the purpose of spy planes on Cocos Island? Add to this, strategic discussions involving the United States, India and Japan and naval exercises between those three countries.

The United States can say this is not containment, as does the Australian Government, but nobody believes them. To continue to say that something that is obvious is not so, is to damage your own credibility. If the United States is genuine in wanting dialogue and discussion with China, what is the need for this military rebalancing?

There are further disturbing elements. The House Republicans added to the defence appropriation bill for the coming year, obligations on the administration "a report on deploying additional conventional and nuclear forces to the Western Pacific region to ensure the presence of a robust conventional and nuclear capability, including a forward-deployed nuclear capability …”

I have some reason to believe that the current United States administration has at some levels begun such discussions. For Australia to be part of such a policy would be dangerous to our future. I would sooner be out of ANZUS altogether than have any nuclear weapons on Australian soil.

American military expenditure is 43% of the world’s total. China’s is 7% or a little over. When China increases her military expenditure, our newspapers have alarmist headlines “China rearming” “China expanding her military”. There is little effort of explanation, there is little logical analysis. There are claims China is being more assertive. Reports are often couched in such a way as to cause concern.

By contrast, if America renews her arms or develops new weapon systems, we generally applaud. We need balance and we need better comprehension.

China has perhaps the most unstable borders of any country in the world. North Korea, Iraq, Iran, tensions between India and Pakistan, Afghanistan. The China nuclear arsenal is not much bigger than Israel’s. The fact that she is now seeking to strengthen her navy is being used by some to create another element of concern. People ask, “Why does China need a navy? For what purpose do they want an all seas navy?” Well there is one answer, China is the last major nuclear state to put her nuclear missiles on submarines. It is necessary for China to do something to increase the viability of a small deterrent force, about the size of Israel or a little more. As comparison, Russia and the United States have 10,000 warheads each.

The future cannot be predicted with any real degree of accuracy. But there are some things that are likely, one of them is that if the United States believes the way to establish good relations with China is to have a military alliance of nations whose purpose is to limit China’s influence, or to contain China, the United States is mistaken. This is the wrong way to preserve peace and security. We should not be part of it.

Such views demonstrate a significant failure to learn from the military mistakes from past decades starting with Vietnam. It demonstrates a failure to realise that the break-up of the Soviet Union created a different post-Cold War world. The United States response is a Cold War response.

The great task for the United States is to recognise that many of the things she wants for herself and for others cannot be achieved by military means. She needs to place much more emphasis on “soft power”, on diplomacy and not allow joint facilities on Australian soil to be used to support containment. Australia should use every effort to persuade the United States that her two-track approach to relationships with China is wrong. We should tell the United States that we will not be part of it and not allow joint facilities on Australian soil to be used to support it.

Historically, China has not been an imperial power the way most European States have been imperial powers and America and Japan. There is no real evidence that they wish to become such a power. We need to understand that what China becomes, how China’s influence is used in future years is not only a function of China’s own internal dynamics, or her perception of the world, but it is also a function of how the United States and countries like Australia and Japan and many others, deal with China. We need a better understanding that China’s policies will be formed, in part as a consequence of the attitudes and policies of the United States and of countries with which she deals.

If the consensus that military containment of some kind prevails then there will be prospects of military conflict and military conflict between China and the United States is the one thing that would be most dangerous to Australia.

In 1956 when many feared that China might invade Taiwan, Eisenhower moved the 7th Fleet in or close to the Taiwan Straits. Many feared war between the United States and China over Taiwan. Prime Minister Menzies then advised President Eisenhower that if there were such a conflict between these two powers, Australia would not be part of it, it would not be our affair. Menzies had a keen understanding of Australia’s own interests, which seems to be quite lacking in today’s world.

Australia needs to be confident as well as independent when we seek to advance values that are important to us. We also need to be clear eyed and understand how other countries see us.

Not least we could argue more strongly for the universality of human rights if we were more effective in overcoming our own deficiencies, especially concerning our current attitude to refugees, which is in clear breach of the Refugee Convention, and our failure to lift the standards of Australia’s Indigenous People.

We are still the only western country with an indigenous minority which continues to have a trachoma problem. If other countries have been able to solve that particular disease, why has Australia failed? Why do too many Aboriginal Australians live in third world conditions?

An understanding of the strengths and weaknesses of our own democracy would strengthen our own diplomacy throughout East and South-East Asia and make us a more effective partner.

Australia’s objective should be to promote peaceful resolutions of disputes through diplomacy, through the application and acceptance of international law. We need to articulate Australia’s national interests as a country allied to, but separate from the United States and with some interests that can differ quite sharply. We need leadership that will tell Australians in plain terms that our security ultimately depends upon ourselves and the relationships that we can build with the countries of the Western Pacific and of East Asia. At the end of the day it is our relationship with these countries that will determine our security.

I put it this way in a submission to the Dr Henry Government White Paper on the future of Australia and Asia. “In short the main objective of Australian policy, which should be publicly stated, would be to contribute to and to help achieve a resolution of any disputes in the Western Pacific through diplomacy or through the application of international law. It should be to deny the use of force except in protection against blatant aggression. It should be to establish a concert of nations with both the United States and China having equal seats at the table and other nations being appropriately involved. We should make it clear that we are opposed to the policy of containment. We should not take any actions that can be construed as supporting that objective and we should not support actions which suggests that military solutions offer an appropriate path to a peaceful Western Pacific, East and South-East Asia. That would be an assertion of Australian policy, principled and practical. It would gain support from many countries throughout the region.”

Ladies and Gentlemen, or should I say on this occasion men and women of Australia, Gough Whitlam and I have been robust intellectual antagonists on some major issues and on opposing sides of one of the most contentious issues of Australian politics. But, on many nation defining, and contested ideas, we have been drawn together and are now at one. I say again, it has been an honour to give the Gough Whitlam Oration.