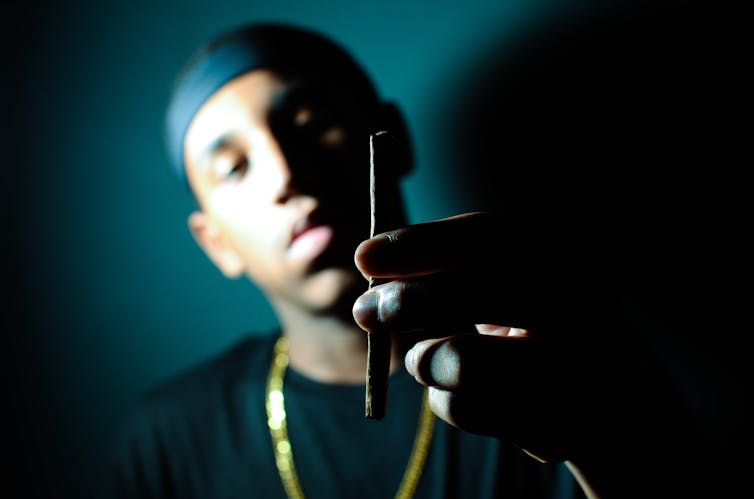

One of the enduring myths about marijuana is that it is “harmless” and can be safely used by teens.

Many high school teachers would beg to disagree, and consider the legalization of marijuana to be the biggest upcoming challenge in and around schools. And the evidence is on their side.

As an education researcher, I have visited hundreds of schools over four decades, conducting research into both education policy and teen mental health. I’ve come to recognize when policy changes are going awry and bound to have unintended effects.

As Canadian provinces scramble to establish their implementation policies before the promised marijuana legalization date of July 2018, I believe three major education policy concerns remain unaddressed.

These are that marijuana use by children and youth is harmful to brain development, that it impacts negatively upon academic success and that legalization is likely to increase the number of teen users.

‘Much safer than alcohol’

Across Canada, province after province has been announcing its marijuana implementation policy, focusing almost exclusively on the control and regulation of the previously illegal substance. This has provoked fierce debates over who will reap most of the excise tax windfall and whether cannabis will be sold in government stores or delegated to heavily regulated private vendors.

All of the provincial pronouncements claim that their policy will be designed to protect “public health and safety” and safeguard “children and youth” from “harmful effects.”

However, a 2015 report from the Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse cites rates of past-year cannabis use ranging from 23 per cent to 30 per cent among students in grades seven to 12 in Ontario, Quebec, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, and Newfoundland and Labrador during 2012-2013. And notes that, “of those Canadian youth who used cannabis in the past three months, 23 per cent reported using it on a daily or near daily basis.”

The report also describes youth perceptions of marijuana as “relatively harmless” and “not as dangerous as drinking and driving.”

Early-onset paranoid psychosis

So what does the evidence say? First, heavy marijuana use can damage brain development in youth aged 13 to 18.

The 2015 Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse study confirmed the direct link between cannabis use and loss of concentration and memory, jumbled thinking and early onset paranoid psychosis.

One of the leaders in the medical field, Dr. Phil Tibbo, initiator of Nova Scotia’s Weed Myths campaign targeting teens, has seen the evidence, first hand, of what heavy use can do as director of Nova Scotia’s Early Psychosis Program.

His brain research shows that regular marijuana use leads to an increased risk of developing psychosis and schizophrenia and effectively explodes popular and rather blasé notions that marijuana is “harmless” to teens and “recreational use” is simply “fun” and “healthy.”

Damaging to academic performance

Second, marijuana negatively impacts neurocognitive performance in teens and users perform more poorly in quantitative subjects requiring precision — like mathematics and senior science.

In 2017, Dutch researchers Olivier Marie and Ulf Zolitz found that the academic performance of Maastricht University students increased substantially when they were no longer legally permitted to buy cannabis. The effects were stronger for women and low performers and academic gains were larger for courses needing numerical or mathematical skills.

Third, legalization of marijuana may increase the number of teen users.

Research from Oregon Research Institute conducted in 2017 showed that teenagers who were already using marijuana prior to legalization increased their frequency of use significantly afterwards. Research from New York University, published in 2014, indicated that many high school students normally at low risk for marijuana use (e.g., non-cigarette-smokers, religious students, those with friends who disapprove of use) reported an intention to use marijuana if it were legal.

Medical researchers and practitioners have warned us that legalization carries great dangers, particularly for vulnerable and at-risk youth between 15 and 24 years of age.

Age of restriction

Marijuana legalization policy across Canada is a top-down federal initiative driven largely by changing public attitudes and conditioned by the current realities of the widespread use of marijuana, purchased though illicit means.

Setting the age of restriction, guided by the proposed federal policy framework, has turned out to be an exercise in “compromise” rather than one focused on heeding the advice of leading medical experts and the Canadian Medical Association (CMA).

In a 2016 submission to the government, the CMA argued that 25 would be the ideal age for legal access to marijuana, as the brain is still developing until then, but that a lower minimum age of 21 should be considered — to discourage children from purchasing marijuana from organized crime groups.

The report argued that: “Marijuana use is linked to several adverse health outcomes, including addiction, cardiovascular and pulmonary effects (e.g., chronic bronchitis), mental illness, and other problems, including cognitive impairment and reduced educational attainment. There seems to be an increased risk of chronic psychosis disorders, including schizophrenia, in persons with a predisposition to such disorders.”

In fact, the minimum age for purchasing and possessing marijuana is going to be age 18 in Alberta and Quebec, and 19 in most other provinces. Getting it “out of high schools” was a critical factor in bumping it up to age 19 in most provinces.

Every Canadian province is complying with the federal legislation, but — in our federal system – it’s “customized” for each jurisdiction.

The Canadian Western provinces — Alberta, British Columbia and Saskatchewan —have opted for regulating private retail stores, while Ontario and the Maritime provinces (Nova Scotia, New Brunswick and P.E.I.) are expanding their liquor control commissions to accommodate retail sales of cannabis.

High school teachers, as of September 2018, may be battling a spike in marijuana use and greater peer pressure to smoke pot on the mistaken assumption that it is “harmless” at any age.

Clamping down in schools

For high school principals and staff, this will be a real test.

By September 2018, the old line of defence that using marijuana is illegal will have disappeared. Recreational marijuana will be more socially acceptable. The cannabis industry will be openly marketing its products. High school students who drive to school will likely get caught under new laws prohibiting motor vehicle use while impaired by drugs or alcohol. Fewer students are likely to abstain when it is perfectly legal to smoke pot when you reach university, college or the workplace.

We have utterly failed, so far, in getting through to the current generation of teens, so a much more robust approach is in order.

“Be firm at the beginning” is the most common sage advice given to beginner teachers. Clamping down on teen marijuana use during and after school hours will require clarity and firm resolve in the year ahead — and the support of engaged and responsible parents.

Legalization of recreational marijuana is bound to complicate matters for Canadian high schools everywhere. Busting the “Weed Myths” should not be left to doctors and health practitioners. Pursuing research-based, evidence-informed policy and practice means getting behind those on the front lines of high school education.

This is a corrected version of a story originally published Jan. 25, 2018. The earlier story incorrectly stated that “one in five young people between 15 and 24 years of age…report daily or almost daily use of cannabis.”