Snowshoeing in the woods on a sunny winter’s day is my idea of fun. When playing in the snow, winter seems to pass faster.

Over two-thirds of Canadians participate in outdoor recreation, according to Statistics Canada. Some 13 per cent of these nature fans enjoy snowshoeing. Compared to skiing, snowshoeing is low key, inexpensive and easy to learn. And it can be done anywhere as long as there is snow.

Snowshoe walks and races were once the most popular winter sports in Canada, long before hockey seized that prize. A century ago, snowshoe clubs were scattered all over the country. The most important was the Montréal Snowshoe Club, formed in 1840. It organized professional and amateur races.

Some Black men once snowshoed over 1,000 kilometres in about 50 days. The epic trek took them from Fredericton, N.B., to Kingston, Ont. Unlike us, these men were not doing it for outdoor recreation.

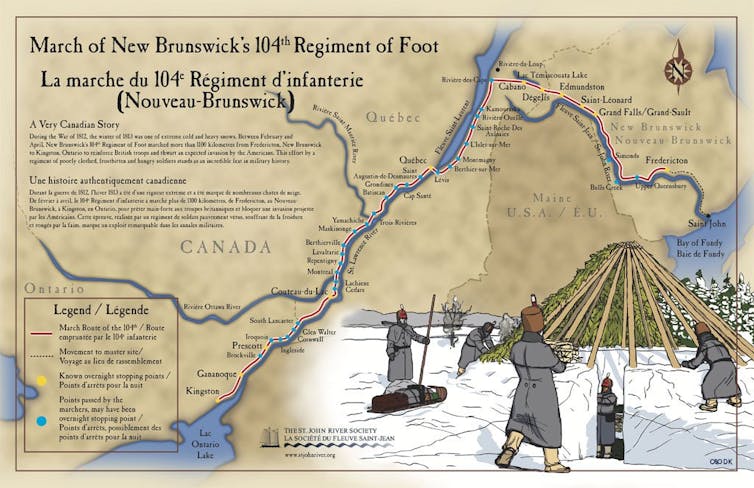

The Black men were part of the 104th New Brunswick Regiment of Foot. The regiment left Fredericton on Feb. 16, 1813, and followed the banks of the frozen Saint John, Madawaska and St. Lawrence rivers until they reached Kingston. They arrived in April.

The 600 or so soldiers of the 104th trekked across the country to bolster Canadian defences against an impending United States invasion. This became known as the War of 1812, even though the conflict was spread out over the next two years.

The Black men in the 104th included Harry Grant, Richard Houldin and Henry McEvoy. They are a minor footnote in the War of 1812 and are usually ignored in accounts of the conflict.

Indigenous technology

The erasure of these Black soldiers of the 104th follows the usual pattern of deleting Black people from the mainstream history of Canada, as their presence or absence raises questions about race and empire, and genocide and slavery.

When Black people are acknowledged, it is usually in reference to the Underground Railroad, and the fugitives’ flight from slavery to freedom in the Great White North. The focus on this part of history ignores the 200 years of slavery in Canada, and how living in its wake continues to shape Black lives today.

Read more: Ancestry ad gets it wrong: Canada was never slave-free

The 104th long march was possible as the army used Indigenous technology and techniques to survive the winter slog. For example, a pair of men each pushed and pulled a toboggan loaded with their food and gear. The toboggan was a traditional Indigenous mode of winter transport.

The men wore moccasins. These Indigenous shoes are perfect for walking on ice or snow as they are light, warm and waterproof.

Then there were the Indigenous snowshoes. They were essential winter gear as they were the easiest way to move in thick snow — if you were a hunter, soldier or just out for a walk.

With just boots on, with each step, one would sink up to knees or hips in the white stuff. In a different situation, this could be lethal. Cold legs are prone to frostbite and frostbite can end in amputation or death. Snowshoes spread the body’s weight so that one can walk and not sink into the powder, and can travel further with less effort.

On a recent snowshoe hike, I passed through a strand of cedar trees, brushing a few twigs as I trudged by. The trees released a perfume that was fresh and invigorating. In my mind, it is the smell of Christmas.

The men of the 104th also liked the cedars. And not just for the scent. They used the branches to make a bed each evening, as they huddled in a makeshift teepee made from saplings and insulated with branches and moss. A blanket and a fire in the middle kept them warm in the sub-zero nights.

‘We were made for this’

Ten years ago, Canada hosted the 2010 Vancouver Winter Olympic Games. The Hudson Bay Company, our iconic retailer of Canadiana, made a marketing campaign with the tagline, “We were made for this.”

In the images of the campaign, pioneers and later athletes skied, hiked and tobogganed in a winter wonderland. Almost all the people visible in the advertisement are white. Thus it made an explicit connection between race, winter and outdoors recreation. It reflected two dominant nationalist mythologies of Canada — as the “the Great White North” and the “great outdoors.”

There are many issues with the advert, but I am interested in how it whitewashed Canadian history and outdoors recreation. What has changed in the past decade?

Snowshoes are cheap to rent at ski resorts and parks and from outdoors recreation stores. Snowshoeing is marketed as a truly Canadian winter sport that is accessible to different age groups, fitness levels and abilities.

It’s a great way for families to spend a winter day outdoors. The marketing photographs are filled with happy white people, in bright neon-coloured jackets, romping in the snow. What is missing from the images are Indigenous, Black and other people of colour. Snow is free, but race plays a role in who is wanted and who gets access to snowshoeing.

The joy of the outdoors

On my snowshoeing ramble, other people were racing through the woods. They were snowshoe runners, dressed in light running gear. Lots of lycra and colour. They shouted greetings as they sailed by.

Something was drilling in the woods. I followed my ears, swivelled my head, and spotted a hairy woodpecker getting its lunch of grubs out of the bark of a tree. The little patch of red on the back of its head was a bold splash of natural colour in a landscape of white snow and beige trees.

I snowshoed about six kilometres on my minuscule trek that day. And then I was done. Tired, ready for hot chocolate and cake in a warm café.

The Black soliders and and their fellow 104th snowshoers would have taken about two hours to do that distance. They had 1,000 kilometres to snowshoe. One day I plan to recreate their historic feat as part of my project of mapping how race intersects with outdoors recreation, geography and adventure travel.