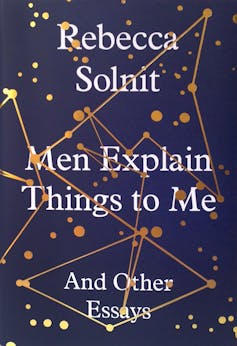

While Christmas shopping in a local bookshop, a handsome little volume stopped me in my tracks as I was leaving. The dust jacket is midnight blue with a gold-foil constellation slightly obscuring the title. The cover belongs to Rebecca Solnit’s book of essays, Men Explain Things To Me. We were in a rush, so I put it down. My partner doubled back and bought it for me as a Christmas gift. He may come to regret judging this book by its cover.

Although slender, Solnit’s book packs a punch. The titular essay starts with a dinner party incident in which, after asking Solnit what her latest book was about, an older man interrupts her answer to inform her about another very important book on the same topic he’d recently read about (but not actually read). It took Solnit’s friend, who was listening in, to point out that he was telling Solnit about her own book.

Solnit entertained the idea that she somehow missed another book published simultaneously on the same, specific topic due to the “confrontational confidence” of this man.

Solnit writes:

Men explain things to me, and other women, whether or not they know what they’re talking about. Some men.

She acknowledges that being a published writer helps her stand her ground, but that:

… billions of women must be out there on this seven-billion-person planet being told that they are not reliable witnesses to their own lives, that the truth is not their property, now or ever. This goes way beyond Men Explaining Things, but it’s part of the same archipelago of arrogance.

This essay leads into a collection of Solnit’s previously published essays on feminism that are thoughtful, well-researched, and in turns funny and painful to read. It’s a measured, unapologetic argument for feminism that I wish I’d been gifted as a younger woman.

The power of Solnit’s writing cannot be summarised by a single quote, but I came back to this passage several times:

Feminism is an endeavor to change something very old, widespread, and deeply rooted in many, perhaps most, cultures around the world, innumerable institutions, and most households on Earth – and in our minds, where it all begins and ends. That so much change has been made in four or five decades is amazing; that everything is not permanently, definitively, irrevocably changed is not a sign of failure. A woman goes walking down a thousand-mile road. Twenty minutes after she steps forth, they proclaim that she sill has nine hundred ninety-nine miles to go and will never get anywhere.

It takes time.

In her essay The Longest War, Solnit addresses rape. A rape is reported in the United States every 6.2 minutes, however the estimated total (factoring unreported incidents) is nearly 5 times that. Meaning there may be almost a rape a minute in the United States. The international examples and statistics that follow are similarly harrowing. Solnit writes:

there are other things I’d rather write about, but this affects everything else. The lives of half of humanity are still dogged by, drained by, and sometimes ended by this pervasive variety of violence.

Solnit reports that the New Delhi rape and murder of 23-year-old physiotherapy student Jyoti Singh and the assault on her male companion (who survived) shocked the world into recognising that rapes are not isolated incidents. A “rape culture” exists and it is a global civil rights issue. She states: ‘It’s your job to change it, and mine, and ours.’

Shortly after I read this essay I came across a multimedia short story addressing the same issue in a way that resonates with Solnit’s call-to-arms.

We Are Angry is a fictional work about an ambitious young Indian woman – she runs a vending machine business without a male business partner, to the incredulity of everyone including her family. The story covers a four day period in which she is the victim of a particularly brutal gang rape. Although fiction, the digital short story includes photographs, videos and audio elements, and links to real reports, statistics and editorials related to Jyoti Singh’s rape and murder.

Author Lyndee Prickitt is a US journalist living in Delhi. She explains her motivation for creating We Are Angry:

As a women and a mother raising my daughter in India I needed an outlet for my fury and a way to raise awareness about the inequitable treatment of women […] instead of adding to the piles of reports and editorials, I wanted to write a poignant fictional narrative from the point-of-view of a victim — a woefully disregarded and unheard voice in patriarchal India. But I also wanted to capture the real swell of anger that was marking a turning point in my adopted country, where the modern and the medieval knock against each other every day.

I consumed the story, including many of the well-edited links to news articles and all the audio and video clips, in one sitting. It was an extraordinary reading experience. It left me agitated, unsettled and deeply angry. I’m not yet ready to experience it again, but I will. And I urge you to. Here.

In this column, I should be commenting on the integration of the multimedia elements into the digital narrative. And I will, later. For now, I can’t critique the form of something while still so raw from the affect of its content. (Although it was the appealing design of one book that initially sparked these thoughts.)

I returned to Solnit’s book, and reread the hopeful passages, such as the one quoted above about feminism taking time. Seeing I was engrossed in his Christmas present, my partner asked whether I was enjoying it. I replied with a smile:

Brace yourself, things are going to change around here.