On 5 March 1984 workers downed tools at Cortonwood Colliery in South Yorkshire, in protest at the Conservative government’s plans to close pits across the country. A week later, National Union of Mineworkers (NUM) president Arthur Scargill called a national strike. Thus began the UK’s final and most significant industrial dispute of the 20th century.

We have learned a great deal about the strike in the 30 years since – that the government planned to declare a state of emergency and call in the army, for instance, or that Thatcher revealed to Cabinet her long-held ambitions “to crush the power of Britain’s trade unions.”

But one further aspect has become clear only over time: this was the first mass industrial dispute played out largely in the media. In a foretaste of the era of the spin doctor, the winning side had the best communications strategy, the clearest narrative and the most compliant media.

Mines to media

Vitally, the miner’s strike emphasised that industrial disputes could no longer be won on the picket lines. The battleground was the media, and Thatcher came prepared. Norman Tebbit, writing in his autobiography, stated: “I do not think that anyone has properly assessed the skill with which the dispute was foreseen and then managed by the government.” Indeed, such media management was rare at the time: the phrase “spin doctor” wasn’t first used in print until later that year.

The government conducted itself during the strike as if it were engaged in an election campaign. This was not just a direct battle with the pit workers but rather an attempt to persuade the public that trade unionism was an inherently pernicious entity. The whole weight of the Conservative Party’s political machine was thrown behind a cause which was regularly depicted as a simple battle between good and evil. It became a debate solely about the personality of the government and the personality of Scargill.

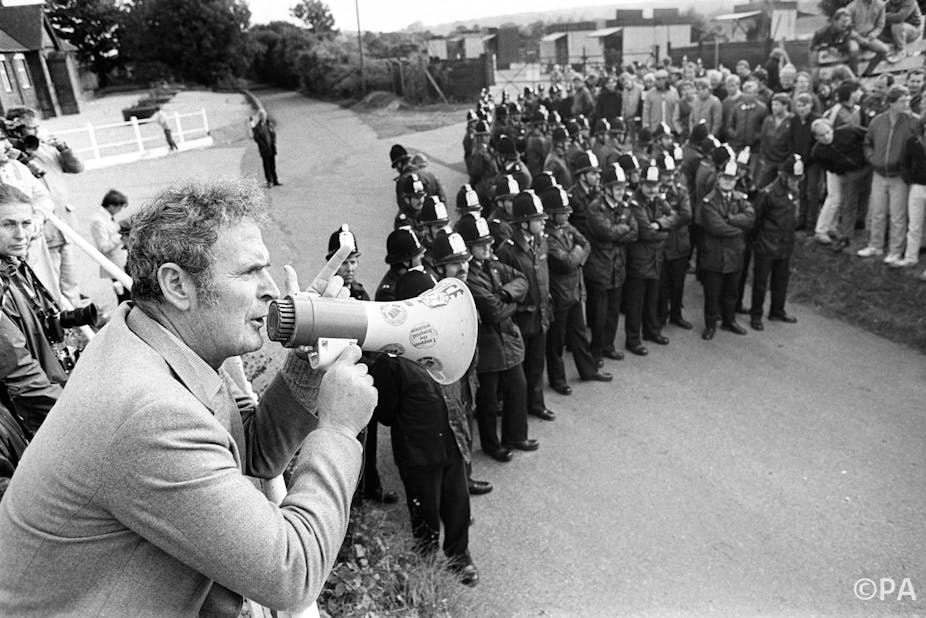

While Thatcher was generally careful to limit her personal proclamations on the strike, as far as the media was concerned Scargill himself was the NUM. He was responsible for issuing each and every national media statement on the behalf of the miners and he appeared at every news conference. As official spokesman, only his words were heard. He embodied the strike.

Scargill did recognise how important television was as a means to communicate with both NUM members and the wider public. However, though he made perceptively timed appearances throughout the dispute, he continually accused the BBC and ITN of distorted coverage, particularly concerning picket line violence. Nell Myers, Scargill’s press officer during the strike, outlined the union’s attitude in an interview with The Guardian in 1985: “The industrial correspondents, along with the broadcasting technicians, are basically our enemies. Responsible for … a cyclone of vilification, distortion and untruth.”

Exploiting the news

By contrast, throughout the strike the government and the National Coal Board (NCB) were able to exploit the news media. They realised that there had to be a massive propaganda operation to convince strikers that there was absolutely no point in them staying out any longer.

The Sunday newspapers set the agenda for other sections of the media – particularly television – and the government was well aware of this. To this day, in the internet age, the same strategy is still adhered to by those seeking to manage the news agenda: launch stories late on Saturday but early enough for other Sunday papers to recycle.

The story would then move onto television. In 1984, the BBC and ITV’s breakfast news programmes dominated and Thatcher’s media strategists ensured that throughout the strike a minister or member of the NCB was available for media comment first thing on Monday mornings. If the timing went to plan the story could be stretched over a further two or three days – longer than if it had broken on a weekday. Through such meticulous planning the government was able to ensure maximum media exposure.

But talking heads on the news weren’t enough by themselves. As the dispute wore on, the government became increasingly reliant on the expertise of advertising consultants. Nicholas Jones, an expert on the media and strikes, points out the government revealed in 1985 that it had spent £4,266,000 on national advertising plus a further £300,000 locally.

In the end, the government won the communication battle by continually highlighting the futility of continued action while miners were steadily returning to work. It ran a highly effective propaganda campaign orchestrated by party strategists who had already won two elections. And, of course, it benefited from a largely compliant media.

In complete contrast, Scargill found it impossible to delegate any of his responsibilities as official spokesman for the NUM. There was no overall communications strategy, his technique was too one-dimensional and his persistence and ingenuity didn’t endear him to those outside the union. In the last great industrial dispute of the 20th century, these factors were crucial.