A fair amount has been written by academics about the history of black cricket, rugby and soccer in South Africa. These writings have given voice to sportsmen and women who were made invisible during the eras of colonialism and apartheid – and even today, after the end of formal apartheid. Such work charts a way forward for creating more decolonised perspectives about the role of black people in South African sports.

But what of the “Cinderella sports”, which fall outside the traditional male team games? These, too, hold fascinating stories about black sportsmen and women who excelled but were largely written out of history.

Take the case of weightlifting and the story of Milo Pillay and his protege, William Ronald Eland, known as Ron. Eland was a world-class athlete forced by the racist attitudes of the then South African Olympic and Empire Games Association to represent Great Britain rather than his own country, South Africa, at the Olympic Games. He later emigrated to North America and served as a technical coach for the Canadian weightlifting team at the 1976 Olympic Games and at the Commonwealth Games two years later.

But official narratives suggest that a white weightlifter, Bennie Oldewage, was South Africa’s “greatest lifter”. In one account, a white weightlifter, Oliver Clarence Oehley, is described as “the father of South African weightlifting”. Meanwhile, one of the pioneers of the sport, a South African-born Indian named Coomerasamy Gauesa (Milo) Pillay, is ignored in historical accounts of the sport.

It’s important to tell the stories of athletes and coaches like Eland and Pillay because offering a decolonised historical narrative reveals an uncomfortable truth: sport in South Africa may have been integrated by law since 1994 but it remains segregated in history narratives. Writing and rewriting black sporting history is a means of redressing this exclusion.

A pioneer

Weightlifting grew out of physical culture during the 19th and early 20th century, where strongmen – and women – picked up heavy weights and all sorts of objects. They evolved into weightlifters or health entrepreneurs in the early 20th century. Later some became body builders, power lifters and women started beauty pageants before they also took to body building and power lifting. This phenomenon is known as the sportification of games and pastimes.

Pillay, who was born in Queenstown and settled in Gelvandale in Port Elizabeth, promoted and grew weightlifting as a sport in South Africa.

According to his own testimony, reported in the newspaper The Sun on 23 November 1951, he started training in 1920 with some train rails and two 50 pound block weights that he used as scales. He was inspired after witnessing German strongman Herman Goerner’s feats in the visiting Pagel’s circus and watching Elmo Lincoln in the film “Tarzan of the Apes”.

In 1929 Pillay established the Apollo School of Weightlifting, which eventually became known as the Milo Academy. It was, unusual for the time, open to all races. It was Port Elizabeth’s first weightlifting club to affiliate to the international Health and Strength League, as well as the city’s (and possibly South Africa’s) first weightlifting club. The Eastern Province Weightlifting Union and the South African Weightlifting Federation emerged from the Milo Academy.

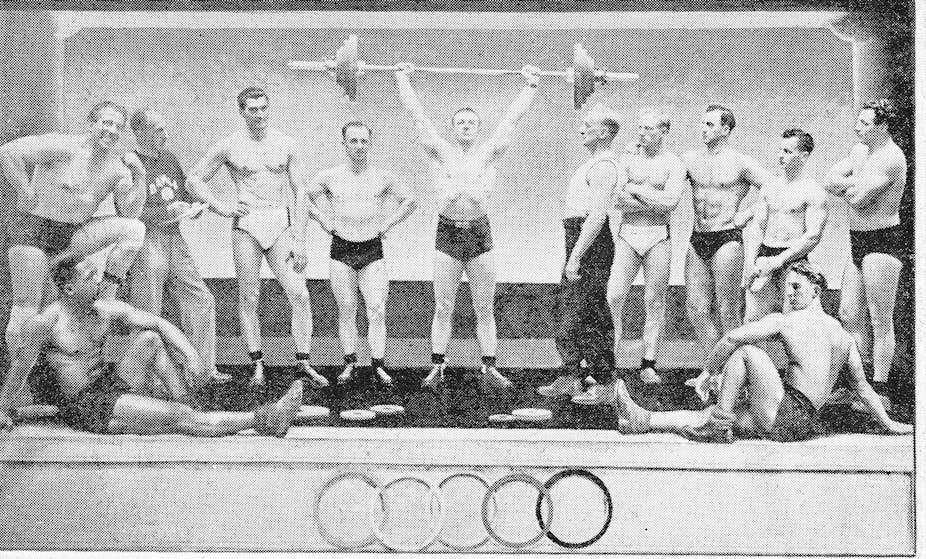

Unconfirmed reports in the Sun newspaper and Eland’s private archives, which I have examined, indicate that Pillay was the only weightlifter selected at the South African Olympic Games trials out of 17 competitors to represent the country at the 1936 Berlin Olympics. But the colour bar – which had protected and favoured white people since the 19th century and would later become a cornerstone of apartheid law – saw him excluded from the team that went to Berlin.

Pillay tore a leg muscle in 1935 and retired from active weightlifting. He became a technical advisor to the Eastern Province Weightlifting Union and continued to push for non-racial sports. In 1947 he wrote to the South African Olympic & British Empire Games Association that the Milo Academy intended to send some non-European amateur boxers, wrestlers, weightlifters and athletes to the Olympic Games in London. He requested official sanction.

The association refused. That’s how Ron Eland ended up participating under the British flag at the 1948 Olympic Games. He went to the Games with the support of a sympathetic white physical culturalist, Tromp van Diggelen. Eland competed against fellow South Africans Issy Bloomberg and Piet Taljaard, who were both white. Sadly, he could not complete his lifts because of a burst appendix.

Bloomberg and Eland remained on friendly terms; Taljaard committed suicide the following year.

Anti-apartheid activist Dennis Brutus said author Cornelius Thomas it was possible that South Africa’s non-racial sports movement actually started with Pillay.

Remembering and re-telling

After 1994, a plethora of sport narratives emerged. These have tended to focus on white sportsmen and women, and have a common thread running through them: that the white South African sport fraternity was a victim of the overall racist system and was devoid of any complicity in apartheid and segregation sport. It also ignores the fact that black sportspeople resisted and actively campaigned against racism.

Telling the stories of Milo Pillay, Ron Eland – who passed away on 12 February 2003 while on a visit to Cape Town – and others is an important way to correct this imbalance in South African sport narrative writing. It’s a way of ensuring that past prejudices in sport are not forgotten. This explains why South African sport history needs to be reclaimed and retold from a decolonised perspective.