It’s Nobel season and who could forget IVF pioneer Sir Robert Edwards who won the accolade for medicine in 2010? More than ever before, reproductive medicine is throwing up new treatments and answers to women’s infertility. In-vitro activation, or IVA, is the latest to make waves after scientists were able to help a woman give birth through a process that involved finding minute follicles in her ovaries.

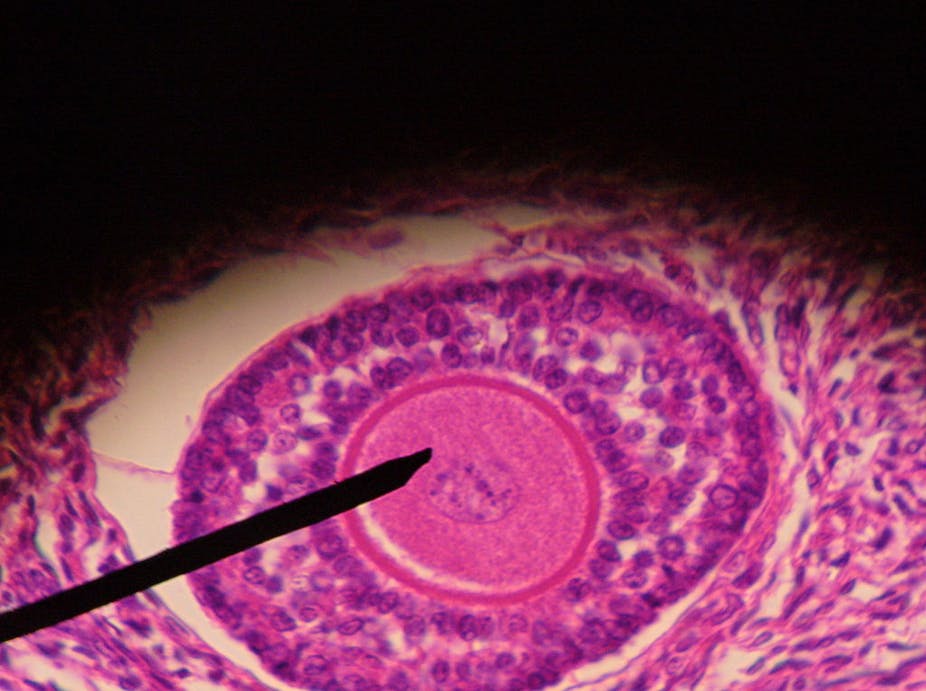

In women’s ovaries the follicles are responsible for producing the eggs and most of the female hormone oestrogen needed for pregnancy. Women are already born with these follicles and the eggs they contain. But the overwhelming majority of these are at an immature primordial stage which means they aren’t capable of either oestrogen or egg production. To do this they must first develop to a more advanced stage, which happens during ovulation every month.

However, because women already have a set reservoir of follicles when they are born, the follicles - and the eggs within them - succumb to the adverse effects of aging, one notable one being progressive damage to the eggs’ genetic material or DNA as women get older. Another important biological process that comes from this limit is the menopause.

Remarkably, for the vast majority of women the age of the menopause is relatively constant at around the age of 51, indicating that the ovary maintains a tight system of checks and balances on its follicular bank.

And exciting new research is unveiling a complex system of signalling pathways through which the ovary maintains this tight leash on how many primordial follicles are allowed to begin development at any one time in order to ensure a supply of oestrogen and egg sand that the finite supply of follicles aren’t used up too early in adult life.

For some women however, this ordinarily tightly controlled mechanism goes awry and any visible signs of oestrogen and egg production disappear a decade or more earlier than expected. Women with premature ovarian insufficiency (POI or premature menopause as some commonly call it) are unable to produce eggs either naturally or with conventional ovary-stimulating drugs such as used with IVF.

IVA - a new breakthrough?

Until now women with POI could still become pregnant but most needed donated eggs to do so. But a team of American and Japanese researchers have reported the birth of a baby to a patient with POI using her own eggs and a technique called in vitro activation (IVA).

The study involved 27 women whose ovaries were both removed and dissected into tiny fragments. In 13 of these women, primordial follicles were found when examined under the microscope. The significance of this was that POI wasn’t caused by the absence of eggs and follicles but because follicles were not being coaxed into developing into more advanced stages.

Once “activated”, ovarian tissue was then transplanted back into the patients and a further eight of these women showed signs of follicular development. And after being treated with IVF drugs to stimulate the ovary, mature eggs were successfully harvested in five cases and resulted in one live birth - the source of the news story.

It’s a landmark paper that successfully translated knowledge about IVA from previous lab-based research into practice. And these results undoubtedly bring fresh optimism when hope previously seemed lost.

But as with all ground-breaking research, these findings also bring new challenges and raise important questions about wider applicability. The papers’ authors have been very measured in considering the potential implications of their findings and alluded to many of the points that the findings raise in my mind.

Working out the maths

IVA was not possible for 14 of the 27 patients in the study, who showed no viable follicles under the microscope. Also, up to the time of the study report, among the remaining 13 women who had ovarian tissue transplanted, eight showed signs of follicle development, five had mature eggs obtained and went on to produce embryos (the earliest pregnancy stage) and one had the live-birth.

So while it is a major advance that proves that IVA can work, it also illustrates that many POI patients may not benefit from IVA. This probably reflects a number of causes of POI. An important challenge for the future will therefore be devising a method that can be used in clinics to identify suitable candidates and avoid invasive surgery for women unlikely to benefit. Also, women with POI account for a relatively small proportion when compared with the wider infertile population.

A needle in a haystack

Can IVA be used to help a wider cross-section of infertile couples? An increasing number of women who seek IVF treatment are well into their forties, when ovarian follicular reserve is known to be very low. One challenge here is actually finding the follicles as they are likely to be few and far between, akin to finding a needle in a haystack.

It also means that IVA is very unlikely to be applicable to post-menopausal women as follicles have all but disappeared by that stage. For older women, IVA will not circumvent genetic and other cellular damage that accumulate in eggs with advancing age and which reduces pregnancy success rates.

A group who could potentially benefit from burgeoning technologies like IVA are young women diagnosed with cancer whose fertility would be jeopardised by the irreversible toxic effects that many cancer treatments have on ovarian follicles. Frozen ovarian tissue biopsies containing primordial follicles obtained from such women before their treatment could theoretically be subjected to IVA and transplanted later in order to obtain eggs.

Notwithstanding these issues, the research is a triumph for translational reproductive research and opens new avenues that brighten the outlook for many whose fertility prospects looked bleak. However, a contracting budget for fertility treatment in the NHS means that even if further evaluation of technologies like IVA validates their use, making them accessible to infertility patients will present an altogether different challenge.