In 2006 I went to South African photographer David Goldblatt’s exhibition “Some Afrikaners Revisited” at the Michael Stevenson Gallery in Cape Town. It was an expanded view of Goldblatt’s body of work, first published in 1975 as “Some Afrikaners Photographed”.

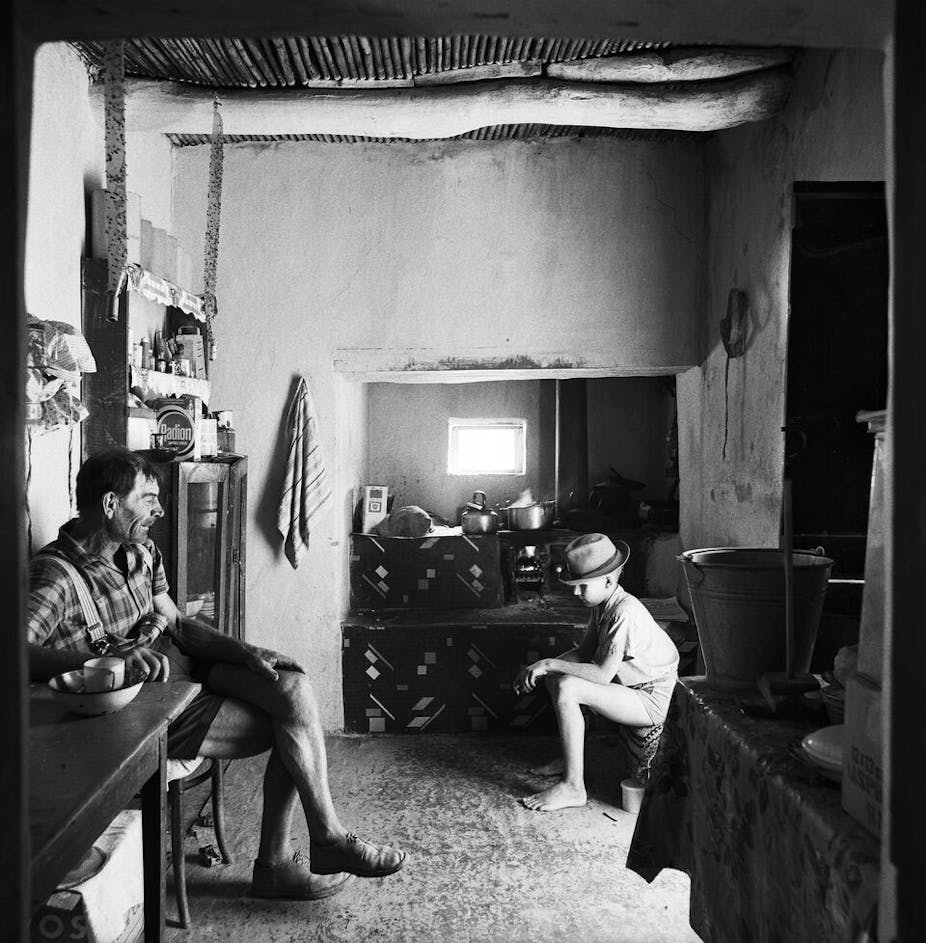

Each of the photographs was surprisingly small. But each was powerful, compelling one to walk over and have an intimate conversation. Like the Dutch Masters, Goldblatt knew how to make the ordinary – even the kitchen of a hardscrabble, rural Afrikaner family – luminescent.

Conversing with those photographs revealed the heart of Goldblatt’s work: his instinctive talent for spotting – and pinpointing – the things that make South Africans uneasy, probing the predicaments at the core of contemporary South African existence, and elaborating upon those unspeakable issues using the sharpness of an image.

Read more: David Goldblatt: photographer who found the human in an inhuman social landscape

Here, among Goldblatt’s images, were their kitchens and the soot of their country hearths (“In Martjie Marais’s kitchen in Gamkaskloof”, 1967), their marriages (“The bride and her parents-in-law”, near Barkly East, 1966), their love for their priced ewes (“J.G. Loots of the farm Quaggasfontein”, where his family had farmed for more than 200 years, Graaff-Reinet, 1966).

Here, juxtaposed, were the immensity of the landscape they loved, and the fear with which they held it. And here, also, was the terror they wielded over those on whom their lives depended – those they loved, feared, and intimidated into a subordination that removed their humanity (“Johannes van der Linde, farmer and major in the local army reserve, with his head labourer ‘Ou Sam’”, near Bloemfontein, 1965; and “Shiftboss with ‘his piccanin’”, underground at Randfontein Estates Gold Mine, Randfontein, 1965).

I could see that my ambivalence about home, language, landscape and belonging were not their lot; it was, in fact, it was an abundance of belonging with which they grappled.

I took a chance and emailed Goldblatt. It led to over a decade of conversations.

Home, language, landscape

Goldblatt himself was an outsider in such belonging, among such situated people. He said during one interview that at a young age he was taunted for being Jewish by the Afrikaner boys around him but added it was at English-medium schools that he experienced serious incidents of anti-Semitism and even sadism,

first at Pretoria Boys High and then at Marist Brothers in Johannesburg.

He found, despite himself, that he liked the company of the Afrikaners who came to get suited at his father’s clothing shop, and was beginning to enjoy the language that he had once disliked so intensely.

When he set out as a photographer, it was to explore what lay at the heart of their power: to explore the contradictory nature that those who are enclosed within protective power structures must, necessarily, cultivate in order to negotiate through ordinary life, while including or excluding those who live outside of the same power structures.

Working class people

Goldblatt initially wanted to do an exposition of the Afrikaner people, making it his business to become acquainted with “some leading Afrikaners and upper middle class people, wealthier people, newly rich”.

But as he went along, he realised that he,

was grossly under-equipped to do something so ambitious, but secondly, in any event, I would not want to do it because I’m not interested in creating encyclopaedias and anyone who ventures to do that is in for a hiding before he starts, because how do you… how do you create an encyclopaedic view of a people?

So, I then realised that… although I’d photographed a number of the fat cats and the more cultured people, in fact, I was more interested in working class people and farmers.

That was partly because I’d met many of these people in the course of working in my father’s shop, in Randfontein (a small town east of Johannesburg). And I knew, from having spoken to them, and having served them, that many of them were salt-of-the-earth people.

And yet at the same time, there was this almost naked fear of The Black. And yet at the same time, there was an intimacy with blacks that far transcended the intimacy that I knew in my own home, with my parents, or among friends and other people in my middle class life.

That is when Goldblatt decided to shelve the idea of focusing on the upper echelons of Afrikanerdom.

I wasn’t very interested in them, because in fact, you see, the support base (and that was one of the things I was interested in)… the support base for the National Party and for the church – the Afrikaner churches – was in the farming and working class Afrikaner community. They provided the votes – the mass votes. So I was especially interested in their values.

Extraordinary work

Omar Badsha – a fellow photographer, friend, and occasional verbal sparring partner on matters of personal politics – remembers that Goldblatt’s work was not particularly admired or successful in the 1970s and 1980s.

My wife Nasima and I were visiting Jo'burg, walking in a shopping centre in Hillbrow. And in a sales bin of a C&A, I spotted a book by Goldblatt. I bought for next to nothing. Nobody was buying the damned thing. But I’d started photography not long before that, and I was taken aback by the work.

It was only in the late 1990s, as the world became more interested in South African photographers’ work for their ability to narrate beyond the spectacular news imagery, that Goldblatt’s work was identified as extraordinary.

He was a master at conveying what must be said, using minimal language. It was determination I saw, without the bravado.

From a decade of writing about his work, I learned a great deal about myself, my place in the world, and how to maintain my relationship with those about whom I write, and the landscapes to which I am drawn. And I learned from him an ability to be in places, without necessarily being attached.

I, and countless others, have his generosity to thank for our journeys through photography, and much, much more. It is now time to say, ngiyabonga, mkhulu: thank you, elder.

Goodbye, teacher.

Some parts of this were originally published in “Returns: 60 Years of David Goldblatt’s Photography.” The Johannesburg Salon. Volume 3 2010 and in “Saying goodbye to South Africa’s legendary David Goldblatt.” Al Jazeera. Opinion. 26 Jun 2018.

David Goldblatt, photographer, born 29 November 1930; died 25 June 2018.