It is difficult to imagine a time when you would need your family and friends more than when you are really ill. So it’s probably not the best time to be separated and sent hundreds of miles away from everyone you know to a hospital at the other end of the country. Sadly, this is an all too frequent experience for children and adults with acute mental health problems.

In the UK about 500 patients a month have to travel more than 31 miles (50km) to access care as acute inpatient beds or services are unavailable in their areas.

A recent report from the independent commission, chaired by ex-NHS chief executive Lord Crisp, called for changes to the way services are commissioned to help reduce the number of patients having to travel far and wide to access appropriate health care.

The report, which is backed by the Royal College of Psychiatrists, recommends that from October 2017, “no acutely ill patient should have to travel long distances to receive care”, as well as the introduction of “a maximum four-hour wait for acute psychiatric care” – in hospital or the community after an initial assessment.

The Royal College of Psychiatrists has previously set and monitored targets for inpatient ward capacity stating clearly that these wards should operate at no more than 85% bed occupancy. But these wards frequently operate at well over 100%.

On top top this, psychiatric wards routinely send the least ill inpatient on leave so they can admit another acutely ill person – meaning there is often more than one person allocated to each bed. The profound suffering of people put in this position with psychiatric issues is almost impossible to underestimate. So how did we get to the point where this has become routine practice?

Community care

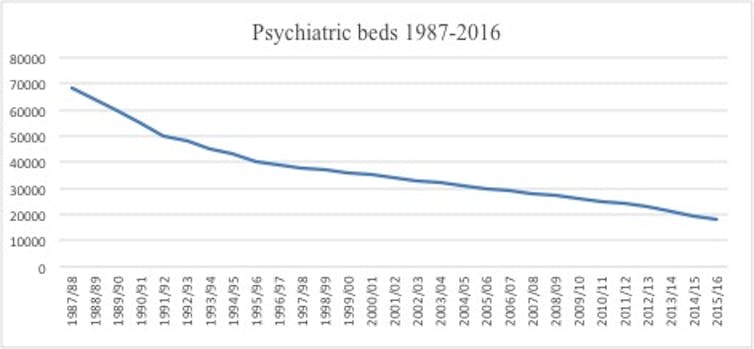

When the large asylums closed some 20 years ago, there was a logical plan to invest in community treatment as an alternative to hospital care. This new community treatment would not only divert individuals from hospital but by intervening early would potentially avoid hospital admissions.

But the money saved from closing down these large and expensive institutions did not follow the patients into the community. This resulted in an under-investment in mental healthcare for decades.

What happens now is that the private sector plugs the shortfall in acute mental health beds when the NHS reaches capacity. Although data is not available on the overall cost, one NHS trust reported spending £4.8m on 70 patients placed in the private sector in one year. So if the aim of reducing the number of acute psychiatric beds was to save money, then the government has failed.

This mental health bed crisis symbolises a cold and business like response to individual suffering, the strategy has been to operate a “just in time” logistics approach to providing acute mental health care. But people aren’t commodities who can be shunted around the country under the guise of efficiency and capacity constraints.

We should be efficient with taxpayers’ money but we also need to be humane and avoid short-sighted savings, and the NHS should have sufficient capacity to be able to admit a person in close proximity to where they live.

Short sighted austerity

It is clear that acute mental health care is costly to the individual and the state. And that mental illness is exacerbated by many factors including substance use and childhood trauma. All of which are malleable.

Early intervention and taking a long-term view is what Public Health England was designed and set up for. Yet this organisation is facing disinvestment to the tune of £200m. Saving this amount now will cost us all dearly in the future, as the prevention of mental health problems is demoted in favour of shrinking public health activity.

When it comes to bed shortages, there is little evidence to support acute in-patient admission beyond its ability to contain and minimise risk. These are not therapeutic environments and for some can introduce an additional risk of danger through exploitation or unwanted sexual abuse.

Instead, we should be looking closer to home as it is family and carers, not professionals who are our greatest asset in providing continuity and compassion for people with mental health problems. Disconnecting families from their loved ones at the time of acute crisis seems bad enough but we compound this by not listening and involving these families at other stages in the treatment. It is staggering to think that while family work has the greatest evidence base it is the least practised. But the time has come to change this.

This crisis has gone on for long enough. Mental health bed cuts put lives at risk and that needs to change. We need to be as radical as the Victorians were when they introduced asylums for the mentally ill. We need a complete rethink of the way we prioritise and provide mental healthcare so that it is fit for purpose, focusing equally on causes as well as the treatment of mental ill health.