As the UK election reaches the final straight, the Scottish National Party has reason to be anxious. First were the predictions of a Tory revival north of the border, then came signs of life from Jeremy Corbyn’s Labour.

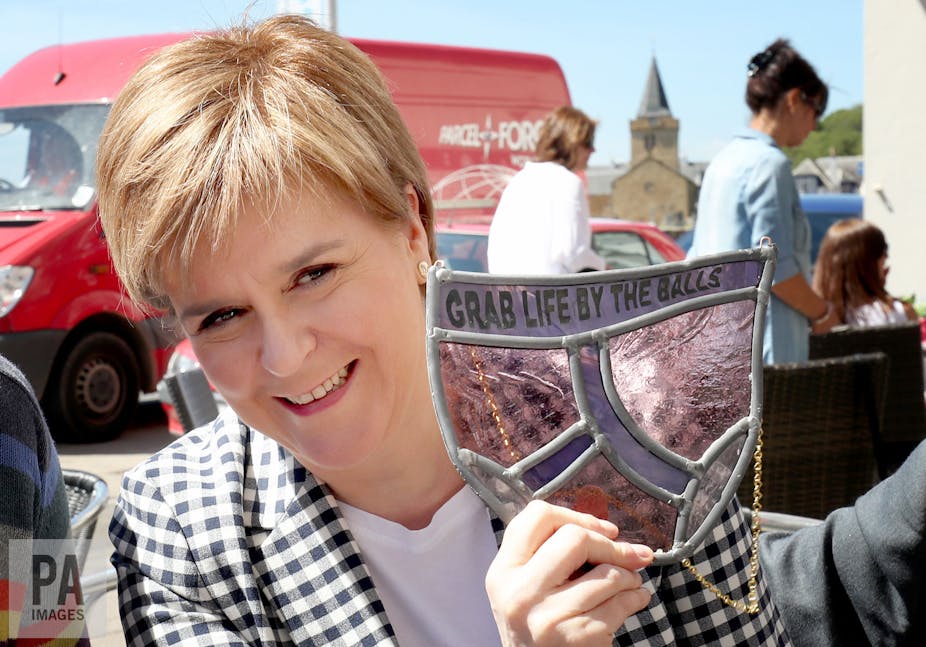

Now SNP leader Nicola Sturgeon’s approval ratings have sharply declined. They have pitched into the red for the first time, hitting -4 compared to +14 as recently as last September. This has made the Scottish first minister the least popular among the party leaders in Scotland. As if to underline the point, she then faced a noticeably hostile audience in the BBC’s Question Time programme.

Widely viewed as an asset until recently, not least in the UK election of 2015 when the SNP swept the board in Scotland, how worried should party strategists be about this change in Sturgeon’s fortunes? How is it likely to affect the party at the election and the prospects for holding a second independence referendum in the next few years?

Indyref blues

The constitutional debate in Scotland is undoubtedly partly to blame for Sturgeon’s drop in popularity – much though she would deny it. Indeed, this was perhaps to be expected when Scottish independence divides the country virtually in two.

Alex Salmond, Sturgeon’s predecessor, saw his approval ratings decline in the run-up to the first independence referendum in 2014. This was mainly about voters who were against independence viewing him more unfavourably. In both cases, the messenger is being viewed by their message to some extent.

Sturgeon had the advantage of becoming leader after that first referendum. She gained the support of voters supportive of independence, but because she did not threaten another referendum at that stage, her disapproval ratings among unionists started low. This did not change during the 2015 UK election, when she performed well in the UK-wide TV leaders’ debate. She convincingly portrayed the SNP as progressive, anti-austerity and standing up for Scotland – demanding greater powers from Westminster.

The mood around Sturgeon seems to have begun to shift after the EU referendum, in which a substantial proportion of SNP supporters backed Brexit contrary to party policy. She may have sounded statesmanlike on television on the morning after the vote, but greater support for a second independence referendum on the back of the Brexit vote did not materialise.

Even after she formally demanded a second referendum earlier this year, support for independence has at best flatlined below victory territory. Even a substantial minority of Yes supporters disagree with holding another referendum any time soon. This has made the SNP vulnerable to attacks from unionists, particularly Scottish Conservative leader Ruth Davidson.

The independence problem

Does all this matter? No and yes. The SNP will be relieved to have seen that Davidson’s approval ratings are declining too, down 26 points to +5. While Davidson’s anti-independence message resonates with unionists, Scotland’s future is also affecting her popularity: her disapproval ratings are increasing among the over 40% or so of voters who support independence.

On the other hand, the SNP have arguably failed to successfully link Davidson to Theresa May’s electoral horror show in England. Sturgeon and her party are now pushing harder with messages about an anti-Tory campaign, but it feels somewhat belated. The party electoral machine does not appear to be functioning as well as it once did.

And Sturgeon’s difficulties are not all about independence. The SNP has been in power for ten years and is vulnerable to criticisms about devolved policy areas, as we saw on her latest Question Time appearance. And under Corbyn, Labour is now firmly positioned to the left of the SNP, along with the Greens. This means Sturgeon’s anti-austerity stance looks weaker than it used to.

Sturgeon has also failed to rule out a possible third referendum should unionism prevail a second time around. Again as we saw on Question Time, this has allowed her opponents to accuse her of adopting a “neverendum” strategy.

The neverendum term was originally coined in Quebec in the 1990s to attack nationalists claiming they wanted to keep holding referendums until they could get the right result. This helped to severely damage the cause. It is now 22 years since Quebec held its second independence referendum, and there is no prospect of a third anytime soon.

It is a near certainty that the SNP will emerge from the UK election with considerably more seats than any other party in Scotland – indeed the same poll that reported Sturgeon’s fall in popularity also predicted that the SNP would win 50 out of Scotland’s 59 seats.

Yet Sturgeon’s waning popularity perhaps points to a much greater danger for her party: that rather like the Parti Québécois, the SNP has become so inextricably linked with independence that support for it rises or declines with the fortunes of the party.

It risks getting caught between a rock and a hard place, with a sizeable number of Scottish voters not wanting another referendum and independence supporters eventually becoming disillusioned by the lack of progress. If so, the chances of a second independence referendum may narrow further as we approach the next Scottish election in 2021. In this winner-takes-all game of constitutional politics, that is certainly a prospect that Westminster’s unionists will be counting on.