If you value the media’s watchdog role in democracy, then the opening words in the deal enabling Channel Nine to acquire Fairfax Media, the biggest single shake-up of the Australian media in more than 30 years, ring alarm bells.

The opening gambit is an appeal to advertisers, not readers. It promises to enhance “brand” and “scale” and to deliver “data solutions” combined with “premium content”. Exciting stuff for a media business in the digital age. But for a news organisation what is missing are key words like “news”, “journalism” and “public interest”.

Those behind the deal, its political architects who scrapped the cross-media ownership laws last year, and its corporate men, Fairfax’s and Nine’s CEOs, proffer a commercial rather than public interest argument for the merger. They contend that for two legacy media companies to survive into the 21st century, this acquisition is vital.

Read more: A modern tragedy: Nine-Fairfax merger a disaster for quality media

Perhaps so. But Australia’s democratic health relies on more than a A$4 billion media merger that delivers video streaming services like Stan, a lucrative real estate advertising website like Domain, and a high-rating television program like Love Island.

The news media isn’t just any business. It does more than entertain us and sell us things. Through its journalism, it provides important public interest functions.

Ideally, news should accurately inform Australians. A healthy democracy is predicated on the widest possible participation of an informed citizenry. According to liberal democratic theorists, the news media facilitate informed participation by offering a diverse range of views so that we can make considered choices, especially during election campaigns when we decide who will govern us.

Journalists have other roles too, providing a check on the power of governments and the excesses of the market, to expose abuses that hurt ordinary Australians.

This watchdog role is why I am concerned about Nine merging with Fairfax. To be clear, until last week, I was cautiously optimistic about the future of investigative journalism in Australia.

Read more: Investigative reporting thrives amid doom and gloom for broadsheets

Newspapers like The Sydney Morning Herald, The Age, the Newcastle Herald and the Financial Review have a strong record of using their commercial activities to subsidise expensive investigative journalism to strengthen democratic accountability by exposing wrongdoing. Channel Nine does not.

Since the formation of The Age’s Insight team in 1967, Fairfax investigations have had many important public outcomes after exposing transgressions including: judicial inquiries, criminal charges, high-profile political and bureaucratic sackings, and law reforms. Recent examples include the dogged work of Fairfax and ABC journalists to expose systemic child sex abuse in the Catholic Church and elsewhere, leading to a royal commission and National Redress Scheme for victims. Another was the exposure of dodgy lending practices that cost thousands of Australians their life savings and homes, which also triggered a royal commission.

The problem with Nine’s proposed takeover of Fairfax (if it goes ahead) is that it is unlikely to be “business as usual” for investigative journalism in the new Nine entity. First, there is a cultural misalignment and, with Nine in charge, theirs is likely to dominate.

With notable exceptions such as some 60 Minutes reporting, Nine is better known for its foot-in-the-door muckraking and chequebook journalism than its investigative journalism. In comparison, seven decades of award-winning investigative journalism data reveal Fairfax mastheads have produced more Walkley award-winning watchdog reporting than any other commercial outlet.

Second, even as the financial fortunes of Fairfax have waned in the digital age, it has maintained its award-winning investigative journalism through clever adaptations including cross-media collaborations, mainly with the ABC. This has worked well for both outlets, sharing costs and increasing a story’s reach and impact across print, radio, online and television.

How will this partnership be regarded when Fairfax is Nine’s newlywed? Will the ABC be able to go it alone with the same degree of investigative reporting in light of its successive federal government budget cuts?

Read more: Australian media at a crossroads amid threats to diversity and survival

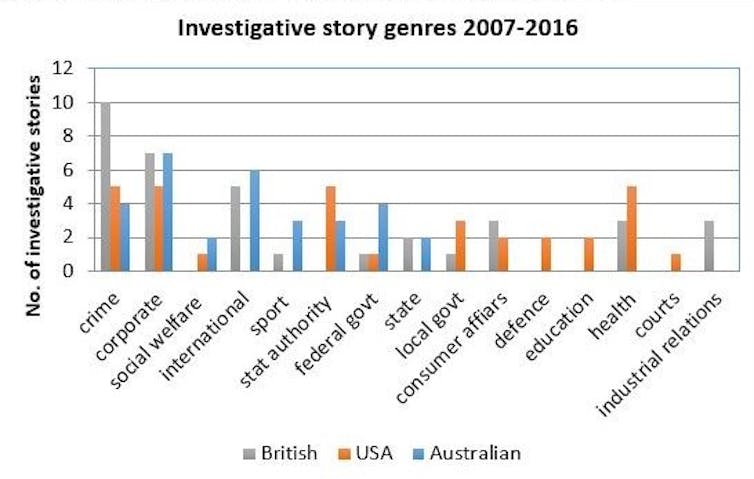

Third, my latest research (see graph) has shown that in Australia, as in Britain and the United States, investigative stories and their targets have changed this decade to accommodate newsroom cost-cutting.

Investigations are more likely to focus on stories that are cheaper and easier to pursue. This means some areas such as local politics and industrial relations have fallen off the investigative journalist’s radar. Here and abroad, this reflects cost-cutting and a loss of specialist reporters.

Echoing this, The Boston Globe’s Spotlight editor, Walter Robinson, warned:

There are so many important junctures in life where there is no journalistic surveillance going on. There are too many journalistic communities in the United States now where the newspaper doesn’t have the reporter to cover the city council, the school committee, the mayor’s office … we have about half the number of reporters that we had in the late 1990s. You can’t possibly contend that you are doing the same level or depth of reporting. Too much stuff is just slipping through too many cracks.

Of concern, Australian award-winning investigations already cover a smaller breadth of topics compared to larger international media markets. The merger of Fairfax mastheads with Channel Nine further consolidates Australia’s newsrooms. If investigative journalism continues, story targets are likely to be narrow.

Finally, investigative journalism is expensive. It requires time, resources and, because it challenges power, an institutional commitment to fight hefty lawsuits. Fairfax has a history of defending its investigative reporters in the courts, at great expense.

Will Nine show the same commitment to defending its newly adopted watchdog reporters using earnings from its focus on “brand”, “scale” and “data solutions”? For the sake of democratic accountability, I hope so.