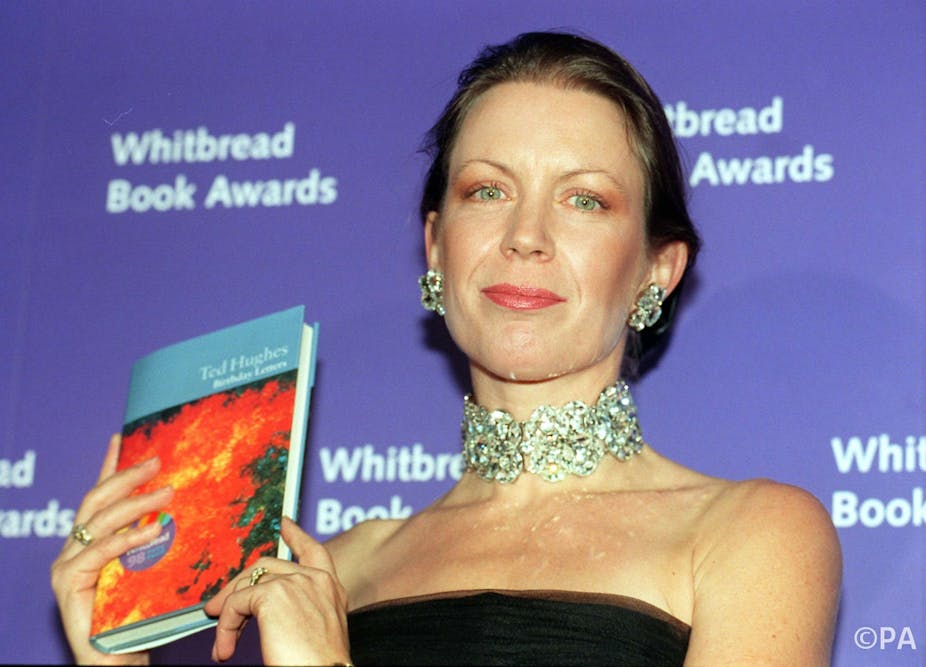

At the opening night of her private view and book launch, poet and artist Frieda Hughes appeared at the door of the Belgravia Gallery in Mayfair, a small but striking figure in a pillarbox-red suit. In the twilight, her bright eyes and ready smile seemed to pour out light. Mysteriously my name had not been on the guest list. She searched my face with lighthouse eyes for a recollection of who or what I was. Finding nothing, she smiled and shrugged and waved me in anyway.

Alternative Values is a series of abstract paintings and poems. The titular painting features an abstracted owl – eyes, beak, feathers rearranged – and the lines:

What we think we see

Is not always the truth, and we should wait

For an alternative view to be delivered …

For someone such as Hughes, such words need no explanation. Since the loss of her mother Sylvia Plath, when Frieda was not quite three, she has been at the mercy of authorised and unauthorised biographers, filmmakers, novelists, journalists and assorted others who have taken the lives of her parents as public property.

The gallery space was tiny. As I walked about, feeling an impostor, unsure of myself, feasting on images with greedy eyes, balancing notebook against wine glass, I was aware of Hughes’s red presence in the room. I found her strangely compelling. Despite myself, and to my shame, I found myself wondering if Plath – whose poetry I find intensely, almost overwhelmingly powerful – carried the same sort of magnetic energy.

But I wasn’t there to squint at her or imagine shared family traits. I was there for the work. The walls were stacked with abstract, textured oil paintings, most framed with chalky grey rectangles; some featured full poems painted onto the surface, William Blake-style; some brief haikus, others ranged across many lines.

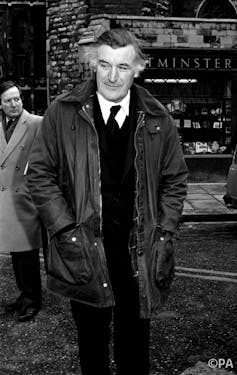

There was a darkness to some of the works. One large painting, called “Mothers”, features a mass of what appear to be dark red tentacles. Another, “After the Funeral”, refers to the loss of her poet father, Ted. Later that night I would meet – briefly – Hughes’s partner, whose face clouded when he heard I was planning to write an article. “A good journalist will write about what’s on the walls,” he said, “not all the old history”. I nodded my agreement. He was right. And this especially at a time when the “old history” is in the news once more; Jonathan Bate’s “unauthorised” biography of Ted Hughes has once again made new headlines of old laundry.

But despite such admonitions, many poems and paintings in the collection are explicitly, devastatingly autobiographical. The most powerful of these are included in the last section of her book, titled Relative Values, which contains painful descriptions of Hughes’ grandmother Aurelia, the break-up of her parents’ marriage, the death of her mother and the final, excruciating piece, “For Shura”. Shura Hughes was Frieda Hughes’s paternal half-sister, who died when her mother, Assia Wevill, also committed suicide. She was just four.

In 2004 Frieda Hughes released a facsimile edition of Plath’s poetry collection Ariel, stating in the preface that according to her mother’s wishes the volume should begin with the word “love” – in a poem about Frieda’s brother Nick, who died suddenly in 2009 – and end with the word “spring”. I could not help noticing that Frieda’s poetry collection also begins with the word “love”. But it ends with the word “death”.

I made a new friend that night, in the shape of Hughes’s friend and Shropshire neighbour, Pauline Breeze. Though there are 30 years between us, I warmed to her immediately. We sat wedged onto two hard chairs at the far end of the gallery, and stayed there for the duration once the room became too full to move. (Later I would realise the chair to my right was occupied by the poet Ruth Fainlight). Pauline, like Hughes, was warm and open - so at odds with the mythology, the “old history”.

Every so often a fraction of Hughes’s light-filled face and red suit would appear amid the throng before disappearing again. Words carried on the air said that she was “thrilled with the turnout”. “There’s a lot of money in this room,” said Breeze, archly, and gave me a knowing look. “They asked me if I wanted a price list.” She shook her head and pulled a “now I’ve seen everything” expression. “I’ve watched Frieda paint most of these. She’s a lovely person. She’s got owls, you know. Eight of them. I had one of them on my arm.”

Breeze wouldn’t let me leave without meeting Hughes properly. And so before I tripped out into the night, high on wine and owlish discourse, an exhilarated Hughes signed my books, apologised for forgetting how to spell October (I said I’d accept any spelling), and gave me an enveloping hug.

On the train, with darkness slipping by the windows, I listened to the audiobook of Bate’s biography. Hughes parents lived in a house called “The Beacon” - and the word “beacon” had maintained a portentous quality throughout Ted’s life. And it occurred to me that Frieda Hughes was something like a beacon, with her broad smile, her red suit, her shining eyes, her owls. This was an alternative view that I just could not have predicted.