Last week’s release of Black Ice – the memoir of Val James, the first African American to play in the NHL – brought me back to when I was a teenager living in Boston. It was the winter of 1978 – the year of the infamous blizzard – when I had my first encounter with a sport that, until then, had only existed as something on TV that would compel me to change stations.

I had an after-school job at a McDonald’s just across the street from the Boston Garden. The location I worked at offered an incentive to employees: if you weren’t scheduled to work, and there was a game going on at the Garden, you could work the before-and-after game rush and receive a free ticket to whatever event was being held.

We never liked the Celtics because of the city and team’s history of discrimination. (Celtics legend Bill Russell would later write that Boston was a “flea market of racism.”) So whomever the Celtics were playing, I invariably cheered for the other team – especially if it had a black star. I recall seeing the silver and black uniform of San Antonio’s #44 George “The Iceman” Gervin and marveling at how he made the finger roll look like ballet.

On one of these game days, I had learned there were a couple of tickets up for grabs. My interest piqued when I heard that Julius “Dr. J” Erving and the 76ers were scheduled to play the home team, so I finished my shift, snagged the tickets and hustled across the street to the Garden.

But I soon noticed that a lot of folks weren’t attired in the usual Celtic green. In fact, no one was. Instead, I witnessed a sea of yellow and black – the colors of Boston’s hockey team, the Bruins. (Apparently, I hadn’t looked at the schedule closely enough.) Before I knew it, I was attending my first NHL game. The only reason I stayed was because I had to work the post-game shift at McDonald’s.

I felt like I’d landed in a different country. It was strange, cold and the fans appeared more belligerent (either due to their drinking or the frigid temperature). I remember glancing around and not seeing another black face, which heightened my nerves; recently I’d been trounced by four, angry white male teenagers – for having done nothing more than waiting at a school bus stop and being black. Still reeling from court-ordered busing to desegregate the city’s schools, Boston was hot with racial animus – and here I was at a “white Boston” pastime. Outnumbered. Again.

Yet I found myself drawn to the game. It was fast. Its qualities seemed at odds with one another, but attractive nonetheless: agility and grace, paired with blistering hits and violent brawls. Soon, I found myself cheering for a Boston team, and I later discovered that the 1977-78 Bruins squad was one of the best in the NHL. Coached by Don Cherry and nicknamed the “lunch-pail gang” for their scrappy style of play, they were the team of Boston’s working people.

While my father worked, he was decidedly not of the working class. A professor and a dean at a local Boston college, he was of the civil rights era and attuned to the racial problems that plagued the city. We never discussed hockey. In fact, none of my friends watched or discussed the sport. For young black males, the stereotype associated with hockey was that it was a game for poor white kids.

In reality, like most “white-dominated” sports (swimming, tennis, baseball, crew, golf, etc.) even though “integration” had happened, we were still denied equal access and acceptance. So as a form of resilience we focused on what we had access to: track and field, basketball and football.

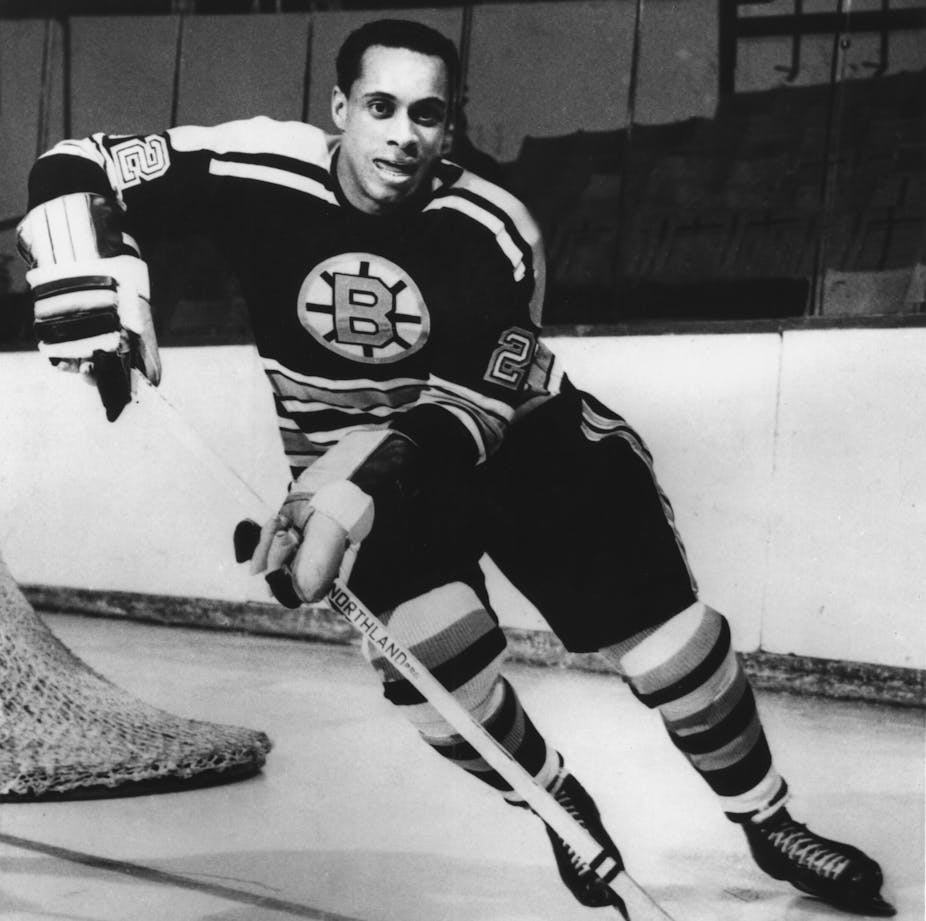

As a young teen, I wondered what the game and fan dynamics would have been like had the Bruins had a black professional hockey player. It wasn’t until I created a university course in 2004 – Race, Sports, and American Culture – that I learned that Boston did have a black player, the first ever, in 1958. He was from Canada and his name was Willie O’Ree. It had been 11 years since Jackie Robinson broke the racial barrier in professional baseball amid a whirlwind of controversy and media attention; but no fanfare accompanied the future Hall of Famer O'Ree – the “Jackie Robinson of Hockey.”

There are at least two reasons for O'Ree’s integration of the NHL going virtually unnoticed. First, O'Ree was Canadian, where racial tension was far less palpable. Second, blacks were in no position to threaten white dominance of hockey. While in baseball there was a cadre of Negro Leaguers waiting in the wings to potentially take power from white ballplayers – Larry Doby, Hank Thompson and Willard “Home Run” Brown, to name a few – in hockey, there simply wasn’t.

For nearly twenty years, O'Ree had no successor. Cracks in the ice, however, appeared again in the late 1970s with Valmore “Val” Edwin Curtis James. Born in Ocala, Florida, James didn’t take up skating until he was a teenager in Long Island, New York. He began his career in Quebec, Canada with the Junior Hockey League, and he would go on to become the first African American player in the National Hockey League when he signed with Buffalo Sabres in 1981; in 1986, he became the first black player of any nationality to skate for the Toronto Maple Leafs. As with many “first and only” individuals breaking barriers, James endured his share of racist jeers and taunting.

Blacks on skates are still a rare sight: in the NHL’s nearly 100-year history, there have been just over 70 black players. In 2003, Black Canadian Grant Fuhr was the first black hockey player to win the coveted Stanley Cup and to be inducted to the Hockey Hall of Fame. As of September 2014, there are about 30 players of African-descent either playing in the National Hockey League, or for an NHL affiliate. Among them are perennial fan favorites PK Subban, Jarome Iginla, Kyle Okposo, Wayne Simmonds and Evander Kane.

However despite these minor gains, the dearth of black players continues. For the past ten years I’ve posed the question to my students: “Why are there so few black hockey players?” Over 100 students from all races, socio-economic backgrounds and geographic regions largely conclude that it is due two reasons: low interest (possibly due to stereotypes of hockey as a “white sport”), and little access to opportunity and training. Both remain formidable barriers to black participation in hockey, making the probability of seeing more Val James’s as low as finding a four-leaf clover in Boston.