It’s been more than 20 years since the Good Friday Agreement paved the way for peace in Northern Ireland. But violence and paramilitarism continue to have a damaging impact on the lives of many young people growing up in Northern Ireland today.

During the conflict, paramilitaries were often linked to the protection of one community from “the other side”. They were motivated in pursuing particular national ethnic identities, such as unionist Protestant or nationalist Catholic. Due to high mistrust of state institutions in some communities, paramilitaries also filled a vacuum, taking on the role of policing crime and antisocial behaviour.

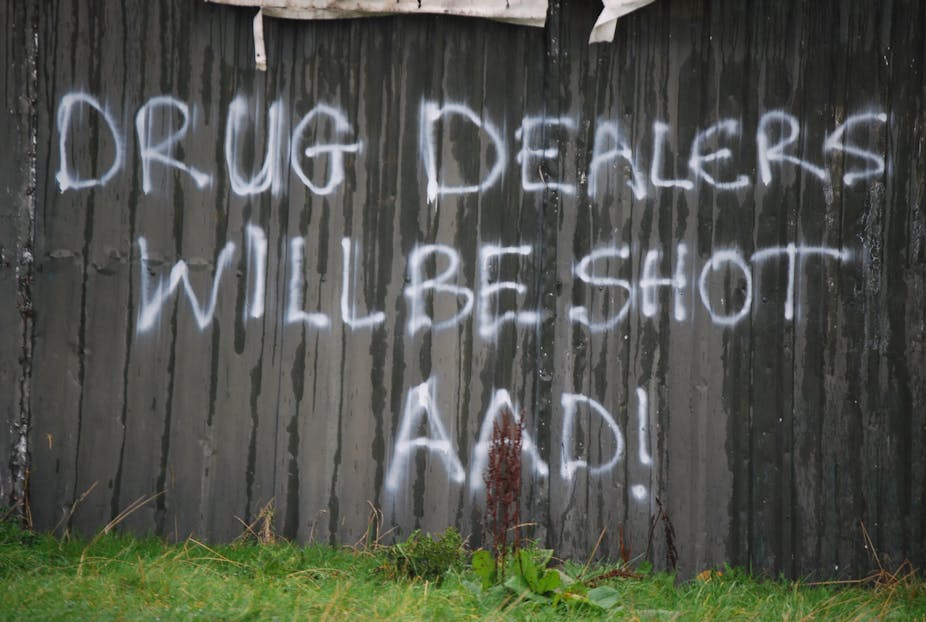

Despite the progress made since the start of the peace process, Loyalist and Republican paramilitaries continue to operate in various guises across Northern Ireland. This has been well known at a local level, but the issue remained off the political agenda until two high-profile killings in 2015 threatened to destabilise peace. The government made a commitment to end paramilitarism through the Fresh Start Agreement that same year.

Encroaching on young lives

Since the first paramilitary ceasefires in 1994, police statistics reveal there have been almost 4,000 recorded “paramilitary-style attacks” – assaults and shootings – in Northern Ireland. Young people under the age of 25 are among the main victims. Their visibility in public spaces and alleged antisocial or criminal behaviour bring them to the attention of paramilitaries.

In our new research we interviewed 38 young people and 29 adult community representatives from three areas of Northern Ireland with a known paramilitary presence. One was a predominately Protestant or unionist area, one a predominantly Catholic or nationalist area, and in one area we collected data from both communities. We found just how pervasive paramilitaries remain in communities affected by the legacies of the conflict.

One 17-year-old girl, Laura*, told us:

If you actually live down here and you run about down here, everyone knows, everyone sees it, everyone I’d say has experienced it in some way, or (came) in touch with the paramilitaries.

All of the young people we spoke to had direct or indirect experiences of paramilitaries. Many had witnessed or personally experienced shootings, fines – demands for money from those involved in the alleged sale of drugs – exiling from the community, beatings, bans, curfews or intimidation at the hands of paramilitaries. Many had experienced a range of these tactics – and on multiple occasions.

Eamonn, aged 18, was issued an exclusion order by a paramilitary group which declared that if he didn’t leave his local area, he would be shot. He was first assaulted at the age of 15 and received two further beatings before this most recent threat. Eammon came to the attention of paramilitaries for alleged anti-social behaviour – being destructive and rowdy in the community. While he acknowledged that he had been involved in some of these behaviours, he emphasised he wasn’t guilty of many of the allegations made against him.

Eammon showed us scars on his body as a result of one beating with a metal bar, which had left him walking with a limp. He recalled:

They bashed my knees too … it was just taking chunks out of me, literally taking chunks out of me.

Eammon was also involved with youth justice system so was already being ‘punished’ for his behaviour. This, therefore, amounts to a form of ‘double punishment’.

Social and psychological impacts

Some of the young people spoke of how they and their families were viewed negatively after they were attacked by paramilitaries, with some in their communities believing they must have done something in order to be targeted. Exclusion from the community also meant the loss of vital support networks – including family, friends and youth and community services.

Aidan, who witnessed his father being shot in an incident in which the 16-year-old was also assaulted, told us of the wider impact on his life:

It’s made my life miserable. I’ve went on drugs, I’ve went on drink, I’ve went off drugs, I went off drink, I went back on them. My life’s a complete shambles … I was in the middle of sitting my GCSEs as it happened, I left school with one GCSE, and that’s because I’d had it since f**king fourth year. That’s the only reason I passed. They f**ked my life up completely.

There was a clear impact on the mental well-being of the young people we spoke to – and they regularly discussed their anger, fear of leaving the house, suicidal feelings, and the use of drugs and alcohol as a coping mechanism. Another boy, Joe, who is now 22, spoke of the long-term fear he’d been left with after he was kidnapped, beaten and threatened with a gun aged 17.

They often saw a link between suicide, or attempted suicide, and paramilitary abuse. As Aaron told us, crying:

I have a friend that was shot … he’s tried to commit suicide at least five times, you know, and he’s never, he’s not left the house. He’s never going to be right again, you know? It’s messed him up completely … How can they justify that?

Our findings come as the Northern Ireland Executive launched a campaign to end the harm caused by paramilitaries. Yet, the absence of a sitting Assembly in Stormont for almost two years continues to hinder serious efforts to tackle this pressing social issue and the realities of so-called “community justice” by paramilitaries in Northern Ireland.

* All names have been changed to protect the anonymity of the people interviewed.