The New South Wales Minister for Education, Adrian Piccoli, has floated the idea of placing a cap on teaching degrees.

In an era of demand-driven higher education, where universities have the option of expanding places to respond to student demand and achieve economies of scale, Piccoli has called for reforms to ensure the supply of new teachers matches the jobs on offer and the needs of schools.

reintroducing caps on initial teacher education courses would be the most effective way to match supply and demand, and attract the brightest students.

Would the capping of initial teacher education places in fact achieve these twin benefits?

Would it guarantee jobs for teaching graduates and steady the supply of teachers in schools while simultaneously raising the quality of teaching and student learning?

Addressing teacher supply and demand

The effective management of supply of teachers is far more complex than simply capping intake numbers to teacher education programs to match the number of available jobs in schools. Nor is it just about meeting the needs of the projected number of future school students.

There is a need for diversity in new cohorts of teachers that will reflect the diversity of the student population.

Teachers require different combinations of skills and capabilities for different student cohorts, schools and school settings. These factors add complexity to the consideration of supply and demand.

The diversity to be found in the initial teacher education courses offered by universities and other providers is a response to this complexity.

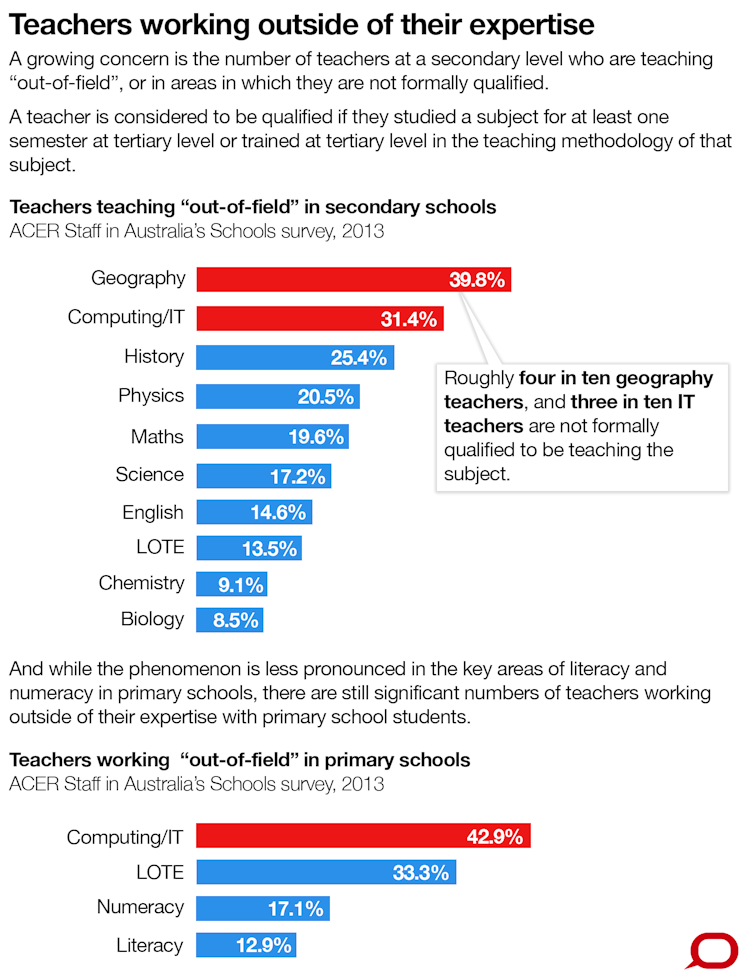

The Productivity Commission highlighted this complexity, observing that while there has been an oversupply of generalist primary teachers for many years, there is also a serious under-supply of teachers in certain subject areas and in schools serving rural and low socio-economic status communities.

Similarly, the Teacher Education Ministerial Advisory Group (TEMAG) pointed to the challenge facing teacher supply in secondary schools, with a finding that around one-third of secondary principals require teachers to teach outside their field of specialisation.

At the same time, there is an oversupply of science graduates who are not employed and are not choosing to enter postgraduate teaching programs.

In Australia, we have 406 accredited teacher education programs offered by 48 providers.

Balancing the supply and demand of teachers so that teaching graduates from any one of these would match the need for teachers in every classroom in every state and national setting requires a degree of insight that is unrealistic.

It is for similar reasons that “manpower” planning in other professions is not attempted.

Improving teacher quality

Is capping initial teacher education places the best way to ensure that those who graduate will have the essential qualities and dispositions to be effective teachers?

A recent paper on primary school teaching quality provides insights from high performing countries.

Finland is often used as an example of attracting the best and brightest into the profession.

Importantly, Finland has only eight teacher education providers and the teaching profession is very highly regarded. Practitioners also work with a high degree of autonomy.

In Japan, where the profession is held in the highest regard, there are over 1000 initial teacher education providers. Teacher education in Japan uses a rigorous selection process further along the pathway before a teacher is recruited into a job.

The common elements in both systems are the esteem in which the teaching profession is held and the quality assurance arrangements for entry level teachers.

Limits of capping

Capping is a measure that can only play the numbers game, and can only affect one point along the teacher development pathway.

It does not guarantee delivery of high quality teaching graduates into the profession, and risks limiting diversity in the profession.

There are four areas where action would offer a better way forward.

1. Strengthen teaching expertise

The quality of pre-service programs in developing teaching expertise is vital. This means developing subject-specific expertise and knowledge about how to help children learn and classroom management skills. The programs that do this well, do so in mutually beneficial partnerships with schools.

2. Agree on standards of graduates

There is a need for more explicit agreement on standards of teaching graduates. We need far greater rigour in the quality assurance process in operation later in teacher preparation – at the point of registration and employment.

3. Better data around supply and demand

We need better national information regarding supply and demand, and the outcomes of initial teacher education.

The lack of national information means many students are choosing teaching degree courses without a clear line of sight on future job prospects, or knowledge of the outcomes of particular initial teacher education programs.

Market information is not only vital for those contemplating a career in teaching, it is equally important for those already in the profession.

4. Form effective partnerships

Initial teacher education should work alongside broader strategies to enhance the teaching workforce. Mitchell Institute’s Powerful Learning and Teaching trial shows how it can be done, with promising practice on how partnerships between pre-service teachers, universities and schools can be developed to ensure effective teaching that lifts student learning.