Since the launch of the first artificial satellite in 1957 – the Soviet Union’s Sputnik 1 – countries around the world have been putting satellites and spacecraft into Earth orbit.

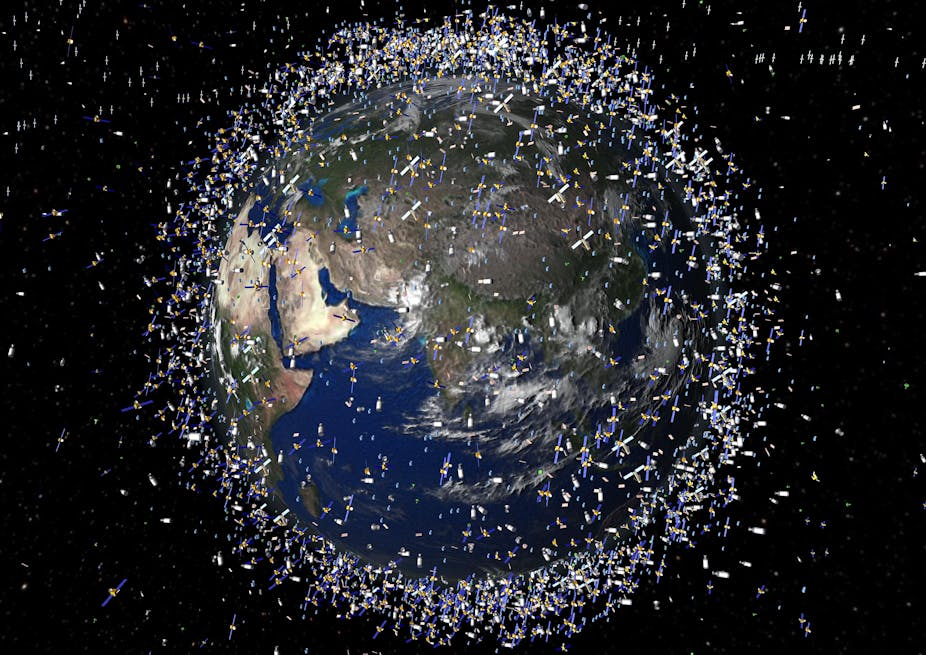

While the majority of objects return to Earth, there are still more than 20,000 trackable pieces of “space junk” orbiting our planet, posing a collision risk for further ventures.

Professor Fred Watson is the Astronomer-in-Charge of the Australian Astronomical Observatory near Coonabarabran in New South Wales.

In this interview he steers us through the world of space junk and discusses decades-old tensions between space scientists and environmentalists.

We’ve been throwing spacecraft into orbit and beyond for more than 50 years. How many defunct spacecraft and pieces of space debris are still up there?

There are around 800 active spacecraft in orbit around Earth. They’re the ones that are currently working – doing jobs, whatever they’re supposed to do, including communications and surveillance.

But on top of that there’s a huge amount of debris. Something like 22,000 pieces of space junk bigger than 100 millimetres across are tracked by various authorities, most notably the Americans.

This includes everything from spent rocket bodies to things not much bigger than a bolt or a bracket. One of those small pieces caused a bit of a flurry last week and sent the International Space Station into panic mode.

In the end everything was OK, but the junk got within 250 metres.

Then there’s the stuff we don’t know about – this ranges from 100 millimetres in length down to the size of fleck of paint and those fragments probably number in the hundreds of millions if not billions.

There’s a lot of space out there, but nevertheless it’s quite badly populated by this junk. Furthermore, the amount of junk is also currently increasing due to phenomena such as the accidental collision that happened in 2009 when a defunct Russian satellite hit an American communications satellite.

There’s an almost constant rain of this stuff coming back through the atmosphere, where it burns up harmlessly – for the most part.

Is it possible to remove any of this junk from orbit?

That’s not really feasible – no technology at the moment would allow us to vacuum up this stuff to clean up space.

So it’s a bit of a waiting game. Hopefully the smaller bits of debris will continue to be braked by the atmosphere and burn up on the way back down but that only works for junk in orbits of perhaps 300 or 400 kilometres.

The high stuff could take centuries to come down.

Perhaps the most crowded bit of space is the “geostationary zone” where you’ve got communication satellites which orbit the earth in the same length of time that it takes the earth to complete one rotation – that’s at a distance of 36,000 kilometres from Earth.

There was a Russian plan announced a year ago to send something up that would target these satellites and de-orbit them, including the defunct ones, all in the name of cleaning up space and making more space available.

What impact have the space sciences had on the environment?

It’s important to recognise that astronomy and space sciences don’t come without an environmental impact. But astronomers regard the planet very much as that “pale blue dot” that Carl Sagan mentioned and so we are, at heart, very concerned about the environment because we know it’s all we’ve got.

But astronomers have fallen foul of environmentalists in the past, with the Mt. Graham squirrels case being one of the most pertinent examples.

The Mt. Graham squirrel is an endangered species that is unique to the Pinaleño Mountains in southern Arizona and in particular, this one species of squirrel lives only on Mt. Graham.

Mt. Graham is a very good site for astronomy and it’s owned by the University of Arizona and in the late 1980s the university wanted to develop a major international observatory there, a plan which culminated in one of the biggest telescopes in the world.

Even though the slopes of the mountain had been developed quite extensively for things such as camping holidays and trekking, the summit was fairly pristine.

It was felt that the number of these endangered squirrels on the mountain was sufficiently low (around 400 individuals) and the mere act of building a new telescope would actually jeopardise the survival of the species.

It’s recognised now that, actually, the survival of the species is more dependent on natural events – such as the cone crop in the pine forest, the temperature and, in particular, forest fires – rather than just the construction of the telescope.

You have previously suggested that, despite clashes between space scientists and environmentalists in the past, the space sciences have had a net positive effect …

We agree that the space sciences have been hard on the environment in a number of fairly limited places. But what you have to balance that against is the benefits that come from it.

One of the places that’s really taken a beating from the activities of space scientists is a place called the Altai Republic which is to the east of the Baikonur Cosmodrome, where Russian rockets are launched.

Several times a month the farmers in that region find bits of space debris raining down on them, and these are blazing rocket bodies – the boosters from [Proton rockets](http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Proton_(rocket).

Proton rockets are the workhorse of the Russian space program – they date from the Cold War era – but they use very toxic materials in their fuel. The stuff raining down on these farmers has killed livestock and has probably caused some illness among the population.

The people of the Altai Republic are really on the frontline of what’s happening with regards to space science’s impact on the environment.

But you only have to look at any kind of remote sensing that takes place on Earth from space to recognise we’ve had huge benefits from space science in terms of our understanding of Earth’s resources, the state of the climate, the state of the earth’s crust.

All of these things are monitored now from space so there’s a very positive side, but one of the biggest positives is what we’ve learned about Mars.

What we now know about Mars and the history of Mars over the last 3 or 4 billion years really gives us an insight into the understanding of our own planet.

The last Shuttle launch is happening later this week. What do you think will be the future of space exploration in the post-Shuttle era and what steps will be taken to ensure any future exploration has as little effect on the environment as possible?

It’s clearly now part of the requisite for any new launch vehicle that you make it as clean as possible in terms of impact on the atmosphere.

The problem with space junk raining down on farmers in Kazakhstan of course doesn’t exist with the American space program – they’ve got the Atlantic Ocean to the east. It’s certainly not ideal to drop things in the ocean, but it’s better than it landing on farms.

The US space program generally uses liquid oxygen and kerosene for fuel, which is a much cleaner in terms of toxicity than some of the things the Russians use.

The US is certainly developing new launch vehicles because for the next two years they will have to rely on Proton rockets and launching from Baikonur.

Clearly its very embarrassing for the Americans not to have their own human launch vehicle available.