Editor’s note: The following is a roundup of archival stories.

The Endangered Species Act, passed in 1973, created a framework for protecting and recovering species in peril and the ecosystems on which they depend. Critics in Congress are pressing to rewrite the law, which they argue limits development and has failed to help many species recover. For Endangered Species Day, we provide perspectives from biologists and social scientists on the challenges of protecting some of the rarest living things on Earth.

Going, going…gone

There are two central arguments for protecting endangered species: First, human activities are pushing many species to the brink of extinction; and second, protecting biodiversity provides us with numerous benefits.

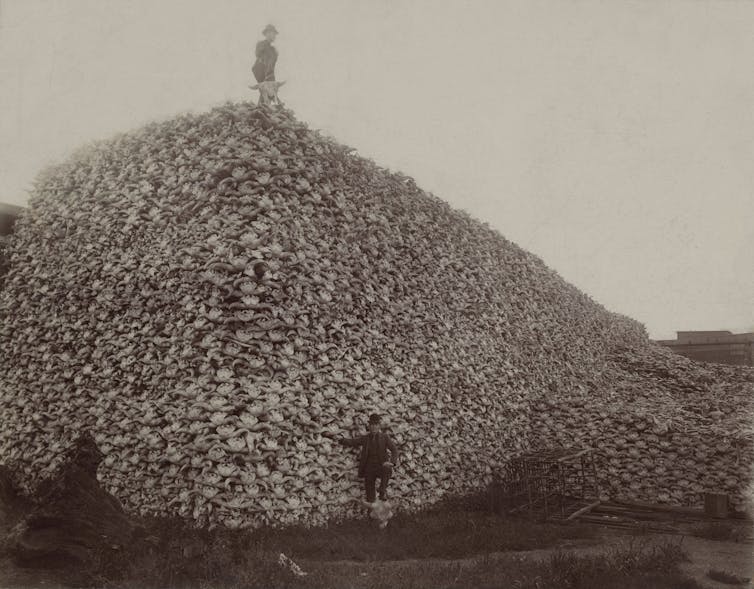

Many scientists contend that we are currently in the midst of the sixth mass extinction in Earth’s history – periods when numerous life forms disappeared from the planet in relatively short lengths of time. Bill Laurance and Paul Ehrlich offer evidence of a sixth great extinction event:

Since 1900, reptiles are vanishing 24 times faster, birds 34 times faster, mammals and fishes about 55 times faster, and amphibians 100 times faster than they have in the past.

For all vertebrate groups together, the average rate of species loss is 53 times higher than the background rate.

Losing biodiversity leaves humans poorer in many ways. As one example, consider biomimicry – creating products based on substances and processes found in nature. As biologist Quentin Wheeler explains, natural selection has created millions of prototypes for totally new designs and materials – but they could disappear before we even identify them:

The extent to which we succeed in creating a truly sustainable future – from renewable energy to degradable materials to cities that function like efficient ecosystems – may well depend on how much knowledge we gather from other species, including those about to go extinct.

A winding road to recovery

Since the ESA was enacted, more than 1,600 U.S. plant and animal species have received protection under the law. During the same period, federal agencies have declared 47 species recovered, including brown pelicans, Louisiana black bears and bald eagles.

Critics argue that the law is not working when so few species have come off of the endangered list. But Peter Alagona and Kevin Brown point out that scientists, conservationists and regulators all define “recovery” differently. These clashing views generate arguments and lawsuits over when to declare that a species no longer needs protection:

Because our definitions of recovery draw from a complex mix of biology, history, geography, politics, culture and law, determining whether an endangered species has recovered or not will always be subject to debate.

Species on the edge

Rescuing a dwindling species is rarely simple. Mexico has banned use of gillnets by fishers in the upper Gulf of California to protect the vaquita porpoise, which often are unintentionally caught in the nets. But switching to trawling gear costs fishers money, reduces their catch and causes damage to the seafloor. In Andrew Frederick Johnson’s view, a much broader strategy is needed:

To put it simply, communities in the Upper Gulf of California need help to reduce both the number of fishers currently fishing and the number of future fishers entering the fisheries.

The Galapagos Islands’ iconic giant tortoises once faced similar peril. Biologist James Gibbs sets the scene:

Over the past 200 years, hunting and invasive species reduced giant tortoise populations by an estimated 90 percent, destroying several species and pushing others to the brink of extinction, although a few populations on remote volcanoes remained abundant.

Now, however, scientists are restoring the tortoises through strategies that include removing feral goats from the islands and “head-starting” baby tortoises in captivity, then releasing them when they have grown to predator-proof size. Gibbs calls the head-starting efforts “one of the greatest and least-known conservation success stories of any species.”

Lost and found

With so much bad news about species that have gone extinct or are teetering on the edge, it’s easy to see these efforts as quixotic. But sometimes the news is good. As Diogo Veríssimo notes, over the past century more than 300 species that were thought to be extinct have been rediscovered, mostly in the tropics. Most of them had been missing for about 60 years when they were sighted and identified.

Veríssimo views these surprises as a valuable tool for convincing people that conservation can work:

Getting these inspirational rediscoveries into the hands of as many people as possible is a first step toward creating a more positive vision for Earth’s future. The timeless principles of storytelling seem like the right place to start. After all, who doesn’t love a happy ending?