How much has Australia committed to fighting Islamic State?

Australia has pledged 600 military personnel and up to eight Super Hornets, which is expected to cost up to $500 million per year. There has also been no time limit placed on its commitment.

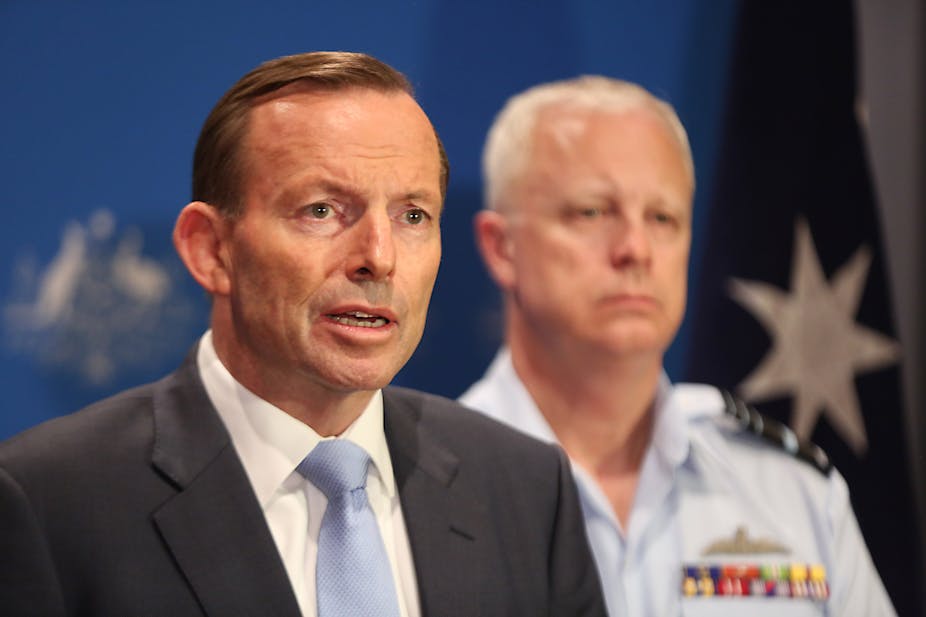

Historically, Australia has typically got in quick, but small, with military commitments to US-led operations. In this instance, the military commitment from Australia is more modest than the 2001 or 2003 commitments in Afghanistan and Iraq. But it is still significant in terms of size, particularly given it is occurring at a time when Australian defence expenditure is on the decline in real terms, with no sign of any increase under the Abbott government.

If the commitment of personnel is broken down, it’s likely a good proportion will be support staff (including the aircraft ground crews, intelligence officers and logistics planners). However, special forces personnel and Australian pilots may be placed at risk.

The risks for pilots will increase significantly if they are tasked with carrying out air strikes into Syria without the approval of the government in Damascus, a scenario US President Barack Obama has openly canvassed. Syria has some of the best air defence systems in the world and the regime will not hesitate using these in an endeavour to shoot down aircraft crossing its airspace without permission.

How does that compare to other countries in the international coalition so far?

Australia is well ahead of other countries in relation to this military commitment.

While Washington has received broad political endorsement from a range of EU and Arab states, even the United Kingdom has been coy about what it will commit in a tangible military sense.

France has commenced reconnaissance air operations over Iraq, and has strongly signalled its support for the US in undertaking air strikes, but other countries have not been so forthcoming.

The risk with Australia’s commitment is that while Arab and many EU countries will be cheering from the sidelines, it will be a small group of Western countries doing the hard-edged fighting against IS and taking primary responsibility for the mission. This is not a good look politically.

It also places an undue burden on a small number of countries to absorb the risks of fighting a terrorist group with global ambitions, which already has a strong track record of massacring unarmed civilians in Syria and Iraq.

With such a disparate coalition of countries involved, will we see a clear, united strategy to fight Islamic State?

Given the different political agendas of the countries involved, there will be undoubtedly be different approaches to the fight against IS. Most of these will be defined in relation to the US position.

Already we have seen Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov castigate the Obama administration for not consulting with Damascus before possible air strikes into Syria.

Iran has also made it clear it will not be supporting the US despite its strong commitment to neutralising IS as a force in the Middle East. Just as every state has its own agenda in relation to the Middle East, they will have disparate – and possibly competing – agendas on how to deal with IS.

Is Australia now at war? Or are there precedents for humanitarian action with military involvement?

There are plenty of precedents for military-led humanitarian intervention. However, this operation is slightly different in the sense that while it is composed of selective humanitarian assistance, much of its focus will be on supporting the Iraqi state.

With IS controlling significant portions of Iraq, the military effort will be strategically directed at dislodging them from key positions and destroying the group’s key infrastructure and ability to conduct sustained combat operations.

No matter what gloss politicians put on it, this mission therefore cannot be genuinely classified as humanitarian per se – remember the inaction of Australia, the US and others over the slaughter of thousands of civilians in Syria and the use of chemical weapons by the Assad regime.

On the question of whether Australia is technically at war, it’s been a long time since there has been a formal declaration of war by any government around the world, let alone an Australian one. It’s therefore hard to characterise the situation from a strict legal perspective.

If and when they see action in Iraq or Syria, the Australian Defence Force personnel will certainly feel like they are at war. However the tempo and scale of operations will probably remain below those undertaken in Afghanistan and Iraq. Yet this will depend largely on how the mission is redefined as it evolves.

Is this Australia’s fight to join?

British Prime Minister David Cameron recently said that even if Britain stayed out of any military engagement directed at IS, IS would eventually come to Britain. He said this was likely to take the form of highly trained, deeply indoctrinated and battle hardened jihadists intent on committing terrorist acts against the United Kingdom. I think this certainly applies to Australia as well, though to a lesser extent given the permissive European travel regulations.

Critics of the Abbott government will maintain that Australia is simply following the US, but it’s hard to imagine Australia standing apart from an operation designed to take on the most powerful terrorist movement in the world today. This movement already has the proven potential to attract Westerners to its cause and ‘repatriate’ terrorists back to their home countries to inflict violent acts.

Will our involvement make us more likely to be a terrorism target?

It is hard to know for sure, but Australia is now likely to be more of a target.

IS propaganda will seek to portray the military force as a colonial intervention intent on committing war crimes against Muslims. This may gain traction in certain quarters and motivate “home-grown” jihadists to carry out attacks against targets in Australia.

However, IS may have planned to target Australia and Australians travelling overseas (who have been historically shown to be more vulnerable than those at home) whether or not Australia joined a coalition effort.

Establishing cause and effect in terrorism is notoriously difficult. The question is ultimately whether Australians are prepared to accept a slightly increased terrorism threat level in exchange for contributing to a military mission that has the potential to decrease the influence of IS.