The 2016 election has made fools of many of us who assured our friends and colleagues that Donald Trump wouldn’t so much as win a straw poll, let alone hold a commanding lead in the Republican nomination battle. But it’s the ongoing Republican civil war that’s now the real break with the past.

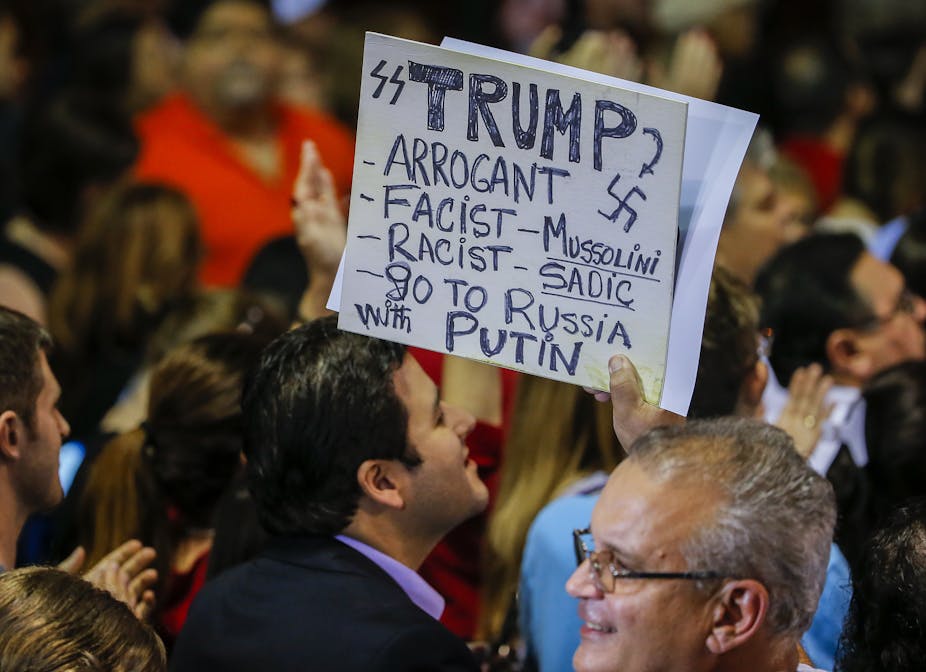

This year’s nomination battle has been more poisonous than any in recent memory. While Donald Trump has led the pack with his lurid, personal attacks, even some of the “establishment” candidates have joined in in response.

After a series of humiliating losses, Florida Senator Marco Rubio went for the jugular, mocking Trump’s hand size and fake tan, even suggesting that the New York tycoon might have wet himself at a recent debate. This was a spectacular breach of the GOP’s long-held “11th Commandment” – “thou shalt not speak ill of any Republican”. It did Rubio no good, and nor did it cow Trump, who continues to roil the party with his incendiary campaign.

But in fairness to Rubio, he was hardly alone among his fellow candidates.

Even as the Republicans are running against Hillary Clinton, their bête noire of two-and-a-half decades, they’re reserving their harshest words for each other – a mistake they’ve largely avoided making since the 1960s.

It’s one thing for someone like Trump to attack his opponents at will, but Rubio, who is of the Republican establishment and therefore a supposed protector of the party’s 11th Commandment, had to play by a different set of rules. It’s interesting that John Kasich, the one establishment candidate left, has studiously observed his party’s once-sacred rule.

Circling the wagons

The birth of the Republicans’ 11th Commandment is often inaccurately attributed to Ronald Reagan, who is said to have used the expression in his successful run for the California governorship in 1966.

The aphorism was in fact coined in 1965 by the California State Republican Party chairman, Gaylord Parkinson, who was desperate to keep the Golden State’s Republicans from splintering between hard-line conservatives who backed Reagan and moderates who backed his opponent. Parkinson implored Republicans to follow a simple rule: “Henceforth, if any Republican has a grievance against another, that grievance is not to be bared publicly.”

He had good reason to be worried. In 1965, the Republican party was in its third decade in the political wilderness, having failed to stop Franklin Roosevelt’s enduring New Deal coalition. The two terms that Dwight Eisenhower served in the White House were a product of the World War II general’s unique personal appeal rather than any endorsement of the Republican banner. During these 30 years, the GOP became known as the party of internal division – even though its various factions and leaders actually differed little on policy.

As it goes with many bad habits, it took hitting rock bottom to kick the party into doing something about it. For the Republicans, that came with the 1964 presidential election.

From rock bottom to Ronald Reagan

As it became clear that hardline conservative Barry Goldwater, one of only six Republican senators to vote against that year’s landmark Civil Rights Act, was on route to winning the GOP nomination, the party elites scrambled to stop him.

Ultimately, the Republican establishment’s efforts proved as futile in 1964 as its efforts to stop Trump are proving now. Goldwater was nominated, many leading Republicans refused to endorse him, and he went down in a landslide defeat at the hands of Lyndon B. Johnson, who went on to pass transformative liberal legislation in areas such as healthcare, education, and immigration.

The hangover from 1964 proved so heavy that leading Republicans quickly resolved to make the GOP a “big tent” party, one that projected unity to the public while simultaneously training its rhetorical fire on the increasingly divided Democrats.

Parkinson’s 11th Commandment became an article of faith for Republicans, none more so than for Reagan, the party’s single most significant and admired figure since the latter third of the 20th century. During this era, perhaps unsurprisingly, the Republican party dominated the presidency and clawed its way into the majority in both houses of Congress.

Signs of strain

But in recent years, as the US’s political culture has become increasingly fractious, the 11th Commandment has come under strain.

The 2000 South Carolina primary, in which John McCain was smeared as having had an illegitimate black child, was an early sign that the party’s internal civility was collapsing. While the crowded 2008 field never quite sank to those depths, its early debates over illegal immigration were spiky to say the least.

The 2012 nomination fight was nastier still, as Newt Gingrich in particular skewered Mitt Romney for his past activities at Bain Capital. The attacks softened Romney up and made it easy for the Obama campaign to define the Republican nominee as an out-of-touch billionaire – even Gingrich conceded he perhaps went too far.

On top of all this, the Tea Party wave that swept the 2010 midterm elections (and carried Rubio into the senate) opened fissures in the congressional GOP that have far outlasted the movement’s peak. The hardcore of conservative representatives elected in the last few cycles have already forced the resignation of one House Speaker.

With Rubio gone, the talk of a chaotic convention followed by a 1964-style Republican wipeout is surging again. And while Republicans remain in good shape at the local level, if the Democratic party wins the presidency again, the GOP will have only held the keys to the White House for eight out of a possible 28 years. That fear seems to be galvanising the party into action – but it may be too little, too late.