The Federal Government’s quest to return the budget to surplus raises many questions and not just about what immediate rationale there is on economic grounds for this strategy.

It also raises deeper questions about our collective view of the role of government in our society.

This might sound a bit grandiose, were it not for the fact that whenever someone enters into the public discussion objecting to fiscal stringency or “consolidation” - to use the fashionable Orwellian term for fiscal austerity - the response invariably involves an outcry about the supposed inherent inability of government fiscal activity to add to anything positive to the economy.

Now, although it might be a stretch to refer to the current government’s return to surplus as fiscal austerity, questioning this strategy will, I have no doubt, unleash these kinds of concerns.

I suspect, in part through many years of verbal bombardment from the wider economics profession, it is in our collective psyche to believe that any budget imbalance should be seen as confirmation of what we always knew – that government can’t be trusted to use our money appropriately and we should be giving them less of it.

Hence the cry of all major political parties, that only their party can deliver lower taxes, by ending the waste and curtailing government spending. Sound familiar?

The long-term role of the economics profession inside and outside of the academy cannot be discounted here: as Keynes himself noted, in trying to get around an entrenched orthodoxy in the 1930’s, “practical men, who believe themselves to be quite exempt from intellectual influences, are usually the slaves of some defunct economist”.

One of the most profound and long-run of those influences is the notion that government activity cannot permanently affect the long-run economic trajectory of economies like ours. At best, the effect of fiscal and monetary policies will be short-run.

Another influence is the idea that markets left unfettered will deliver desirable social outcomes. Certainly the GFC should give pause for thought at least in respect of this idea.

As to the first idea, it tends to mean for fiscal policy that other than in exceptional circumstances, such as the GFC, there is little justification for fiscal stimulus or for budget deficits, particularly since deficits will generate public debt.

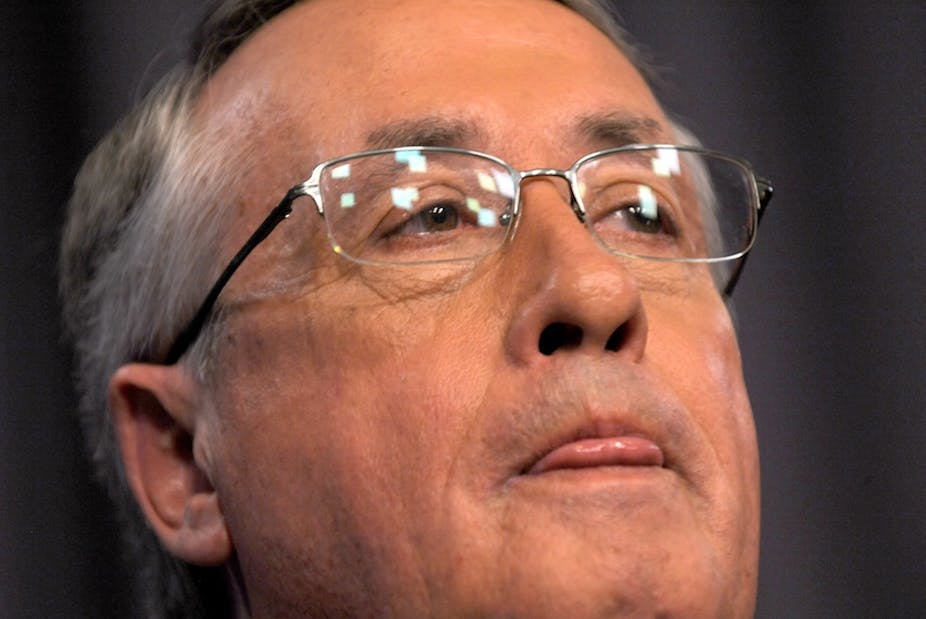

And located not very far away from this idea in another part of our collective psyche is a third idea – reinforced intensely in the years of Paul Keating and John Howard – that the optimum amount of public debt is zero.

Combining these ideas that government macro policy can do little to the long-run growth of the economy, that deficits generate debt and that the only good public debt is no public debt, one is confronted with a forceful brick wall against which progressive thought on fiscal policy and macro policy in general must contend.

No matter that our public debt is very small as a proportion of our GDP, that it is under most plausible scenarios a debt which should show no signs of exploding relative to GDP.

No matter that there may be an asset somewhere to be found – for example, a school, hospital – corresponding to the liability which a public debt represents. No matter that it might be worth pondering about the social return from such assets when considering the debt which might arise from bringing it into being.

It is this brick wall that provides the real backdrop to the corner into which politicians have painted themselves around the topic of a budget surplus. Their ability to achieve a surplus or balance the budget is spuriously taken as a measure of fiscal responsibility.

Spurious, because it relies on the equally spurious notion that the budget balance is something completely under the control of the government of the day.

Spurious also because the budget being in deficit in and of itself does not mean a runaway public debt problem. In fact, a stable public debt to GDP ratio is consistent with a permanent budget deficit in a growing economy.

The argument - which, to be fair, has been put by some within the economics profession - that constraining spending to bring the budget into surplus may weaken an economy and weaken the flow of revenue of the government and make it harder to achieve the surplus and retire public debt seems to have bounced off this wall.

It’s like being in a meeting where no one has a clue what the speaker is talking about – but everyone is politely nodding. Neither the Government nor the Opposition has articulated any clear justification for the necessity of a surplus in the forthcoming budget and I do not think they know of any such justification.

Neither has provided any serious response to the warnings that their preferred policy might weaken the economy further.

The nearest to any response is a claim that this will allow for lower interest rates. But this is an old furphy which supposes a hard and fast link between the budget balance and interest rates. This link is without solid theoretical or empirical support.

Both sides of politics seem to be relying on the view that “common sense” would tell you that this is the “right thing” to do.

This situation would be less of a worry but for the fact that the cuts which will be made to achieve the surplus will likely impact on the social wage – health, welfare and education.

As is so often the case, it will be those least able to defend their standard of living which will bear the brunt of the polity’s inability to think beyond the policy brick wall.