With three elections in one month, the complexities of sub-Saharan Africa are on full display. On August 4, Rwanda’s Paul Kagame won reelection by a widely anticipated landslide. Next up is Kenya’s Uhuru Kenyatta, who is hoping to retain power in a hotly contested vote on August 8. In Angola, meanwhile, longtime ruler José Eduardo dos Santos is retiring, but the voting that begins on August 23 will make little difference in a country that amounts to little more than a one-party state.

Both Rwanda and Angola are host to authoritarian governments accepted by populations who still remember recent civil wars, and in the case of Rwanda, genocide. Opposition groups cannot organise freely and fairly; already the European Union has said it will not send observers to Angola because important preconditions for unhindered travel by observers were not met.

But as has become the manner of these things, many observer groups who do attend will doubtless declare these elections “peaceful and credible”. And technically speaking, they will be. Governments have learned how to play the election game, skilfully managing them as public relations efforts for a global audience.

Everybody seems to have adopted the Singaporean style, whereby a small opposition is allowed to run but never to win. A powerless opposition is almost desirable, providing just enough evidence that “democracy” is alive and well to keep outside powers on board. The West accepts Singapore as a democratic ally – the same status that many African governments now seek.

August’s most interesting contest is being fought in Kenya, which votes on August 8. The government and opposition are neck-and-neck. All parties are seeking to avoid the violence of 2007, which resulted in Kofi Annan mediating a coalition government and the prospect of a presidential indictment before the International Criminal Court. President Uhuru Kenyatta fought off that indictment thanks to a paucity of credible evidence. Many suspect the evidence was not forthcoming because of plain old witness intimidation.

This grubby history leaves both parties tarnished by questions of past violence, but it has an upside: both main presidential candidates, Kenyatta and Raila Odinga, have worked together in the coalition government of 2007 to 2012 and know each other very well.

The election is something of a throwback, not only to recent elections fought by the same two men, but to the post-independence contests between their respective fathers. In some ways, it seems Kenyan democracy has barely advanced, except in the increasing scale of corruption and oligarchic conspicuous consumption.

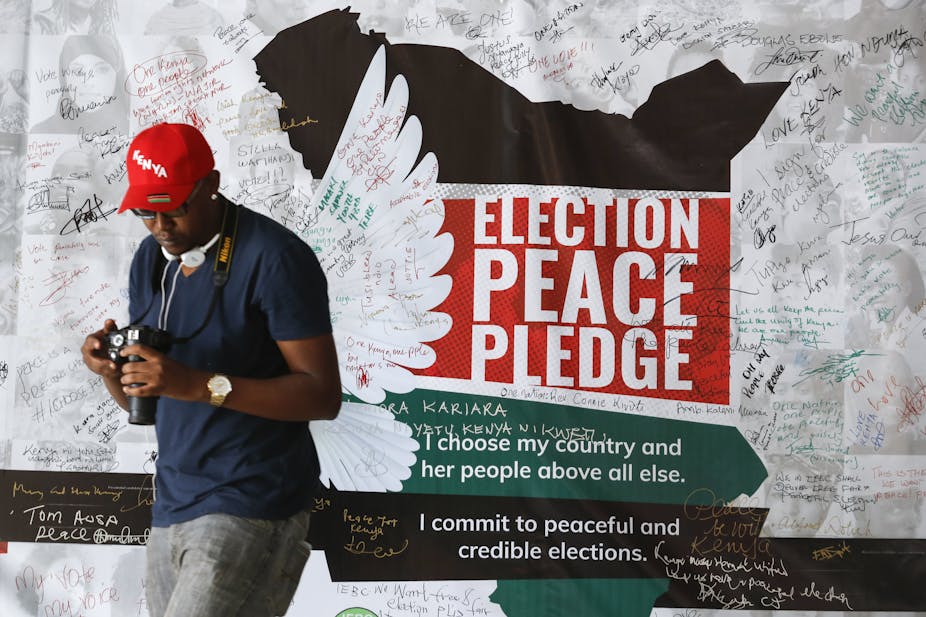

Yet in other ways, Kenya has never seen an election quite like this. It will be very closely monitored, and European observers began deploying weeks beforehand. All parties are going out of their way to dampen down prospects of violence. It’s also a digital campaign; smartphones have now achieved mass penetration, and online campaigning is thriving.

But as the US found at its last election, this is also the era of fake news. YouTube and social media are full of confected CNN and BBC “reports” of a massive government polling lead – but no such advantage has shown up in any of the extensive opinion polling that’s actually been released.

Onward, not upward

Taking a longer view, these are messy times for Africa’s democracies. Some have recently held sound elections, then turned authoritarian almost overnight. A case in point is Zambia: during the 2016 campaign, no love was lost between the incumbent, Edgar Lungu, and opposition leader, Hakainde Hichilema. When Lungu came out triumphant, Hichilema challenged the result to no avail. He now languishes in prison on trumped-up treason charges that would be immediately dismissed if Zambia had a robust court system.

Zimbabwe, meanwhile, is expecting elections in 2018. With the opposition in disarray, Robert Mugabe is determined to stand. He’ll be 94 by polling day; behind closed doors, his own party is feverishly debating who will succeed him, since even he cannot expect to serve yet another full term.

And come 2019, the lead act will be South Africa. The battle to succeed Jacob Zuma is well underway within the ANC’s ranks, where discontent with the incumbent leader spills into the open. Even Winnie Mandela has joined the chorus lamenting the state of her party, saying “something is very wrong with what we have done”.

However welcome the end of Zuma would be, the luminaries jockeying to succeed him are figures from the past, not the new blood South Africa desperately needs. Still, perhaps it’s just as well that unlike in Kenya, the liberation generation doesn’t yet have any sons and daughters running to keep the same family in office for decades to come.

This piece has been updated to reflect Kagame’s victory.