Last month a fire destroyed 23 timber buildings in the the Norwegian heritage town of Laerdalsoyri.

Another fire ripped through the important Korean gate of Sungnyemun in 2008. This one was the result of an arson attack.

Both incidents highlight the fragility of heritage places.

Fortunately in the case of Sungnyemun the building had been meticulously documented in 3D with laser scanners. That work was commissioned by the South Korean Cultural Heritage Administration, and the data has since been archived with CyArk.

An archive that saves buildings and monuments

CyArk is the world’s leading, and non-profit, digital cultural heritage archive. It has been archiving some of the planet’s most important heritage places since 2003. Using the 3D scans of both the original building and post-fire rubble and remains, the timber pagoda atop the gate in Sungnyemun has been meticulously reconstructed.

No, the reconstruction is not the same as an undamaged building, and “authenticity” is itself a debated subject in heritage preservation. But faster, more accurate and more affordable techniques in digital 3D documentation are helping create more digital records of our cultural heritage.

Many heritage sites are remote or under threat and access is restricted. The hazards facing heritage places are numerous: not only fire, but the wear of time and limited conservation funding. Sites are also threatened by human conflict or activity, and broader natural disasters.

Many heritage places cannot be expected to last into the coming centuries, but it is not impossible to give them a digital legacy.

Australian CyArk heritage

Australia’s first CyArk site is Queensland’s relatively little known Fort Lytton. The Fort was built in the 1880s to defend against a presumed threat by the Russians and is perched at the mouth of the Brisbane River.

In 2013 the fort was captured by CSIRO and The University of Queensland’s School of Architecture, using CSIRO’s Zebedee handheld 3D laser scanner.

The new Zebedee is a Eureka Prize-winning piece of technology.

Closely following Fort Lytton, The Scottish Ten’s detailed scanning of the Sydney Opera House become the second Australian data set archived by CyArk. The Scottish Ten is a joint collaboration between CyArk, Historic Scotland, and The Glasgow School of Art’s Digital Design Studio to digitise Scotland’s five UNESCO World Heritage Sites and five internationally prominent heritage properties.

3D data of Sydney’s Pyrmont Bridge and rock art in Kakadu National Park have also since been added to CyArk’s growing Australian collection.

Keeping up with technology

Digital cultural heritage practises are advancing at a rapid rate globally. Archaeological and scanning teams are traversing our planet.

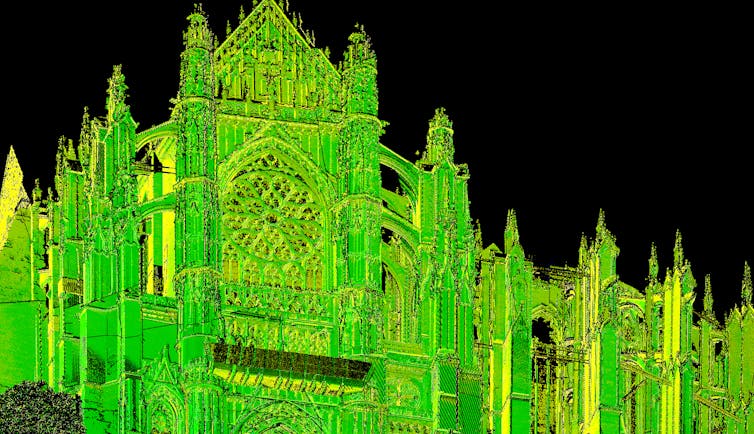

CyArk now has 3D data representing heritage places from all seven continents. From the pyramids of Mexico, to gothic cathedrals in France, to San rock art in Africa, to Shackelton’s Antarctic exploration huts, the archive continues to grow.

Yet the problem of digital data’s longevity is well known. The possibility exists for precious and costly data sets to be lost on failed hard-drives, destroyed in floods or fires, or simply thrown out.

Data access also falls victim to technology obsolescence far too often.

CyArk’s mission is to safely store heritage data, and it has partnered with Iron Mountain to provide a “gold standard” solution for their archive. Final archival copies are housed deep in the belly of Iron Mountain’s facility in Pennsylvania, USA. CyArk also shares permissible data with the public on a web platform that gives visitors the chance to explore these places.

The scanning of heritage places also allows scholars to study these places in ways that have been very difficult in the past.

UQ School of Architecture’s analysis of the racial segregation of Peel Island’s Lazaret (Leper Colony), for example, was informed by empirical data and accurate 3D mapping of the buildings.

The Peel Island site was captured in just a few hours using CSIRO’s Zebedee laser scanning technology. Previously, scholars had taken weeks to painstakingly measure the dilapidated buildings by hand, and had only fully recorded a fraction of the total buildings.

Further scans of Peel Island will help us complete an intercultural analysis of the island’s use over time, including uses of the Quandamooka traditional owners. The island’s digital preservation will make it accessible for future generations of Quandamooka people and the broader community.

The CyArk 500 project

Last October CyArk launched its most ambitious project yet: a call to action for the global community to scan and archive 500 of the world’s most endangered or significant heritage places in the next five years.

Scans are supplemented with historical information, photographs, architectural data, archaeological data, and whatever is available, to create a comprehensive narrative.

The first round of nominations for the CyArk 500 closed in December with the second round open until March 31 this year. Heritage professionals and the public alike are encouraged to nominate sites for inclusion, especially those in danger of destruction. The first step in the nomination process is a letter to CyArk outlining the qualities of the place and why it should be digitally preserved.

What about the cost, you ask? CyArk is establishing a 500 Fund to support this process. Money will be raised from individual donors, heritage groups or agencies and the private sector.

As we recognise the threats to heritage places and lament the loss of some physical sites, the scanning of heritage sites means we can preserve physical places better with more complete records. We will also enjoy virtually visiting digital heritage areas that we might never have been able to access in person.

The data captured, combined with the histories of the places, will help tell the story of each site and create a lasting digital legacy for the story of humanity.