Genomes from the 500-year-old remains of King Richard III and a direct living descendant are to be sequenced by scientists, which could reveal more about the life of the last king to be killed in battle in England.

Genome sequencing gives a full picture of someone’s genetic make-up and DNA and can reveal information such as their susceptibility to certain diseases, like diabetes or cancer, to the colour of their eyes and hair.

It’s still a relatively new technology and while it is increasingly being used on modern subjects, only a small number of ancient individuals have had their genomes sequenced. These include Otzi the Iceman, who was revealed to be the first known sufferer of Lyme disease, and some Neanderthals. Richard III, whose remains were found under a car park in Leicester, will be the first named individual to undergo such testing.

Turi King, research lead at the University of Leicester, said the work might reveal a little about how Richard looked but also whether he suffered from particular health problems, and – as geneticists discover more about the associations of genes to particular characteristics – what he may have developed had he lived.

“The sort of thing we might find is if he was predisposed to things such as obesity or Alzheimer’s,” she said. “Sequencing could also give us evidence about the effect of bacteria and viruses. It will be interesting if we see any evidence of infection.”

She added: “We’re still learning about which genes code for what … and a complex number of interactions.” Further work could reveal information on things like skin colour for example.

Richard had no direct descendants but to further understand heredity, the researchers will also sequence the genomes of Michael Ibsen, a 17th generation nephew.

“We know [Richard and Ibsen] share mitochondrial DNA, which is passed through the female line, but we don’t know whether they share any of the other bits,” King said. “Given the time, we wouldn’t necessarily expect them to share a lot. We’ve had many people get in touch saying they’re related to Richard III. But we all are to varying extent.”

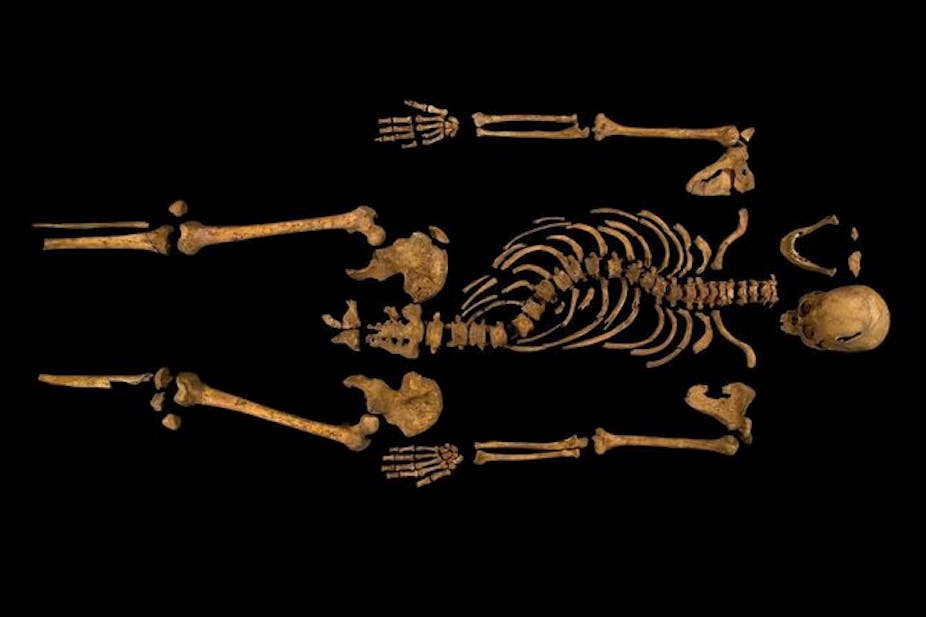

While the project has the potential to reveal much about the medieval king, there are problems in working with DNA that is 500 years old – there might be low amounts and it can be fragmented.

Michael Hofreiter, an expert in ancient DNA from the University of Potsdam who will be collaborating on the project, said there were special considerations when dealing with ancient DNA.

“We need to use really sensitive techniques to make sure we lose as little DNA as possible in the different steps we use,” he said. “People working with modern DNA often lose about 90% of the DNA in each step – extraction, library building, for example – but as they can start from large amounts, they do not need to be bothered. At the same time it means it is easy to contaminate the samples with traces of modern DNA that are flying around in the environment (we all shed DNA at all times).”

He said fragmented DNA could make it difficult to assemble a genome. “Think about it this way, you take a picture and cut it into a jigsaw puzzle of 50 pieces – when you sequence modern DNA you try to reassemble this picture. With ancient DNA you do the same, except that you have the same picture as a jigsaw with 1,000 or more pieces (the numbers are bigger, but the ratio gives you an idea).”

“If you cut your picture in small enough pieces as with ancient DNA, some pictures end up being the same, so you cannot place them unambiguously. Therefore, ancient genomes are never 100% complete.”

Richard III reigned for only two years before he was killed at the Battle of Bosworth Field in 1485. His death marked the end of the War of the Roses and a period of political turmoil.

Dan O'Connor, Head of Humanities at the Wellcome Trust, which is part funding the project, said information such as hair and eye colour could also tell us a lot about the portraits made of the king and how he was viewed politically. “There are no contemporary portraits – all postdate Richard by 40-50 years.”

The remains of Richard III are due to be interred and any samples taken will be returned. The team plan to make their findings public, although it will be about a year before they report.