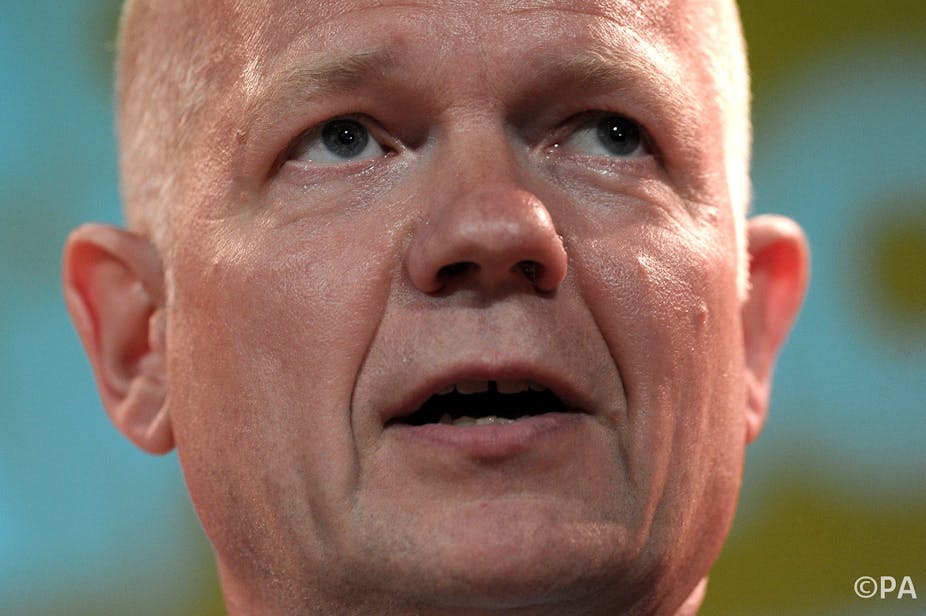

Mix the Scots and sport and you’re bound to end up with trouble. Just ask William Hague, who gaffed this week that Team GB would break a leg at next month’s Commonwealth Games in Glasgow – forgetting that unlike the Olympics, the four nations compete separately.

Then supermarket group Morrisons waded into similar territory by piping out English World Cup anthems in Scottish stores. While the Scots once again ponder whether to support anyone but England, the latest British Social Attitudes survey confirmed that large numbers of Scots still think they get a bad financial deal from the union. We asked our panel whether the Scots’ sense of victimhood is spurring the referendum debate.

Karly Kehoe, senior lecturer in history, Glasgow Caledonian University

The Scots aren’t taking themselves too seriously – if anything, they aren’t taking themselves seriously enough. I come from North America and as we all know, confidence has never really been a problem for us. It is a problem for many Scots, particularly for younger Scots.

It has certainly improved since I first arrived here in 1998, but class is a big problem. People are judged on what their accent sounds like, what school they went to, and what part of the country they come from. This does not promote engagement and it actually prevents long-term socio-economic improvement.

This can be linked back to the union and participation in the empire. Unlike England, Scotland had never had colonies of its own, but to make up for this it was a full participant in the union after 1707. There are a minority of Scots who believe that they have been the victims of the English, but history tells us that this wasn’t actually the case.

The Scots were always attempting to improve their position. By the mid-nineteenth century a number of Scots started to call for equal recognition as a partner in union. This recognition was never delivered and in many respects, we can see this issue coming back now - hence the process of referendum.

Scotland is also a classic example of a small nation next to a bigger one. Canada experiences the same thing being next to the US. The smaller, less powerful nation will always feel disenfranchised, and often the bigger or more powerful neighbour doesn’t even notice.

That’s not to say that the Scots are too sensitive about how they are treated though. William Hague is an example of how Westminster politicians keep getting it wrong. If there was more recognition of the four nations, there might be more contentment with the relationship. The problem is that the partnership of the four nations hasn’t always been given due respect.

John McKendrick, Senior Lecturer, Glasgow Caledonian University

It is true that when it comes to sport, we do get ourselves wound up if the likes of Andy Murray or Stephen Gallacher are described as British, particularly when they are competing against the likes of Tim Henman or Justin Rose, who always seem to be described as English. It always seems that we are British when we are winning, but Scottish when we are losing. Does that mean that we are overly sensitive, highly strung and generally guilty of taking ourselves too seriously? I think not. Irony is a big part of our sense of humour. Poking fun at each other and ourselves is an art form at which we excel.

So we might be irked by the crassness of the “little Englander” mindset that is all-too-often characteristic of pundits and broadcasters. But, we can excuse this as misplaced enthusiasm or downright ignorance. It is far less acceptable when leading politicians make the same mistakes. So when William Hague calls for Team GB to deliver a “spectacular performance” at this year’s Commonwealth Games, we are within our rights to question whether this is more than a laughable gaffe. At the very least, it suggests that our neighbour does not always really appreciate who we are.

But I wouldn’t want sporting gaffes or allegiances to feature too strongly in the referendum debate. Too much is at stake. The ignorance of the broadcasters and the ineptitude of some politicians might seem to give credence to the core arguments of the yes campaign – that we are misunderstood and are being short-changed. Not getting our fair share of oil wealth might seem to chime with not getting our fair share of national credit for sporting success, but let’s not make this a major part of the campaign.

Neil Blain, Professor of Media, University of Stirling

I see a number of contradictions here. If you take the Scottish Social Attitudes survey, it shows that the whole idea of British identity is falling away in Scotland. It mainly survives among older people because of the legacy of post-war Britain and for other reasons. Yet if you look at younger people, there’s no overwhelming support for independence among them.

We can be sensitive about things like William Hague’s gaffe, even though it was pretty minor really. Yet we can be remarkably accepting of a number of the implications of union. For example this week, polls showed that a lot of Scots believe we should house Britain’s nuclear weapons whether or not there’s a yes vote in September. The union could mean the nuclear annihilation of the west of Scotland, but as a nation we seem to be quite relaxed about it.

In the referendum debate, people are worried about what will happen in the autumn or in the next year or two, or about the currency. But if you look further ahead, Boris Johnson wants a north-south crossrail to add to the east-west one. Then there’s high-speed rail. These projects will suck more investment into London from the rest of the country. Sometimes we might be sensitive about things, but why are we not worried about becoming a region of the UK that’s cut off from economic investment because of projects like these?

Examples of the Scots being slighted are just things we like to talk about. Some people like to go online and complain about Hague or Morrisons, but we have been hearing these kinds of things all our lives.

It’s just the same as how the London-based media don’t know the difference between British and English news. London and the South-East don’t face towards Scotland. If we are really in emotional turmoil, why aren’t the BBC and Channel 4 in their London broadcasts being constantly bombarded by objections from Scots?

In September, for the first time since 1707, if people are unhappy, they can do something about it. For outsiders who have heard us complaining down the years, if we vote no there will be a response when we complain in future: why didn’t you do something about it? There’s a sense that if you did do it, we would probably take you seriously as a country.

You’ll find previous panel discussions here.