The Scottish police force’s latest unhappy revelation must have sent a shiver down the necks of the Scottish justice department: Phil Gormley, the new chief constable, previously supervised the division of the London Metropolitan Police which included the controversial undercover unit the Special Demonstration Squad.

In one fell swoop, Scotland’s “top cop” has become embroiled in one of the most controversial issues in UK policing in the past 20 years – although he has said he knew nothing about the Special Demonstration Squad at the time. The unit deployed officers who infiltrated radical groups such as environmentalists and anarchists, who in some cases had sexual relationships with group members and even fathered children. The connection is the last thing that troubled Police Scotland needs and the timing could not have been worse: environmental campaigner Kate Wilson recently won damages against the police after her two-year relationship with undercover officer Mark Kennedy. Several other women have received out-of-court settlements as a result of the matter.

Controversy has dogged Police Scotland since it was formed in April 2013 by merging Scotland’s eight regional forces. Though such as centralised model of policing has been resisted in England and Wales, Police Scotland’s first chief constable, Sir Stephen House, had spent his entire career in England, including a stint as assistant commissioner of the London Met, before becoming chief of Strathclyde Police in 2007. Once in Scotland, the combative House quickly became an advocate of a single national force for Scotland at a time when it was a minority political view. He began winning the argument when the SNP-led Scottish government changed its position on national policing ahead of the 2011 Scottish elections.

Tough tactics

Following House’s promotion to run the new merged force in 2013, he wasted no time in making his mark on Scottish policing. Police Scotland used stop-and-search tactics on a huge scale, following the model he used in Strathclyde that in 2010 made such searches four times more common than in the whole of England.

In Police Scotland’s first year alone, 520,000 searches took place. These were overwhelmingly carried out on young people (including hundreds of children under the age of 12), without the officer having to specify the law under which anyone was being searched. Following general outcry, the Scottish government carried out a review in 2015 overseen by a senior human rights lawyer who concluded that the procedure was of “questionable lawfulness and legitimacy”. The government duly made Police Scotland change the policy.

The whole worrying episode could be traced to a target-led culture endemic in the Metropolitan Police and across senior police management structures. This Met influence on House was also seen in another Police Scotland controversy – the use of armed police. The small number of Scottish armed officers were deployed on routine incidents. This led to scenes of police with guns patrolling the streets in Inverness and other rural communities. Following protest and political anger, this practice was also rolled back.

When House fell

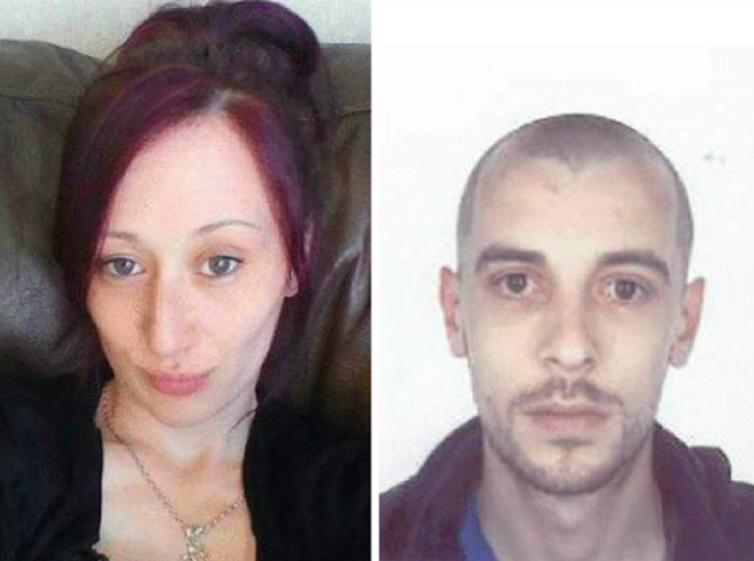

House’s resignation last August, a year before his contract was supposed to end, came amid criticism of these aggressive policing operations, though things were brought to a head by another controversy – the car-crash deaths of John Yuill and Lamara Bell near Stirling the month before. Although a passer-by had reported the crash to the police call response unit, no one acted on it for several days and the call was not recorded on the system.

Yet House’s departure did not end the unsettled structures of accountability within the new national structure. Moving from locally based forces to a centralised one has not been balanced with equivalent democratic national watchdog bodies. It was this vacuum that allowed such aggressive policing in the first place.

It seemed counter-intuitive to say the least to replace House in December with Gormley, another senior Met officer with absolutely no experience in Scotland. There is the advantage that he has no association with the previous regime, but since his arrival, it has been déjà vu for the Scottish force and the government. Even before the Special Demonstration Squad story, Gormley had inherited the problems caused by the revelation that Police Scotland hacked journalists’ data to discover their sources without observing due process. The Scottish parliament is investigating the issue, but Police Scotland is reportedly refusing to allow some serving officers to appear in front of the relevant committee. It adds to the sense that some senior people at Police Scotland regard themselves as untouchable.

As if all this wasn’t enough, news of Gormley’s role at the Met comes amid strong calls for the Pitchford Inquiry into the Met’s Special Demonstration Squad and undercover policing to be extended to Scotland. There is strong evidence that the undercover officers in question were operating during a number of Scottish protests. So far, the UK government has resisted broadening the remit of the inquiry.

In sum, the new Scottish chief constable is in for a bumpy ride. These London chiefs and policing practices, curiously imported by Nicola Sturgeon’s SNP government, are likely to become a central issue in the upcoming elections. The repercussions for Scottish society are likely to be felt for a long time. We haven’t heard the last of this to say the least.