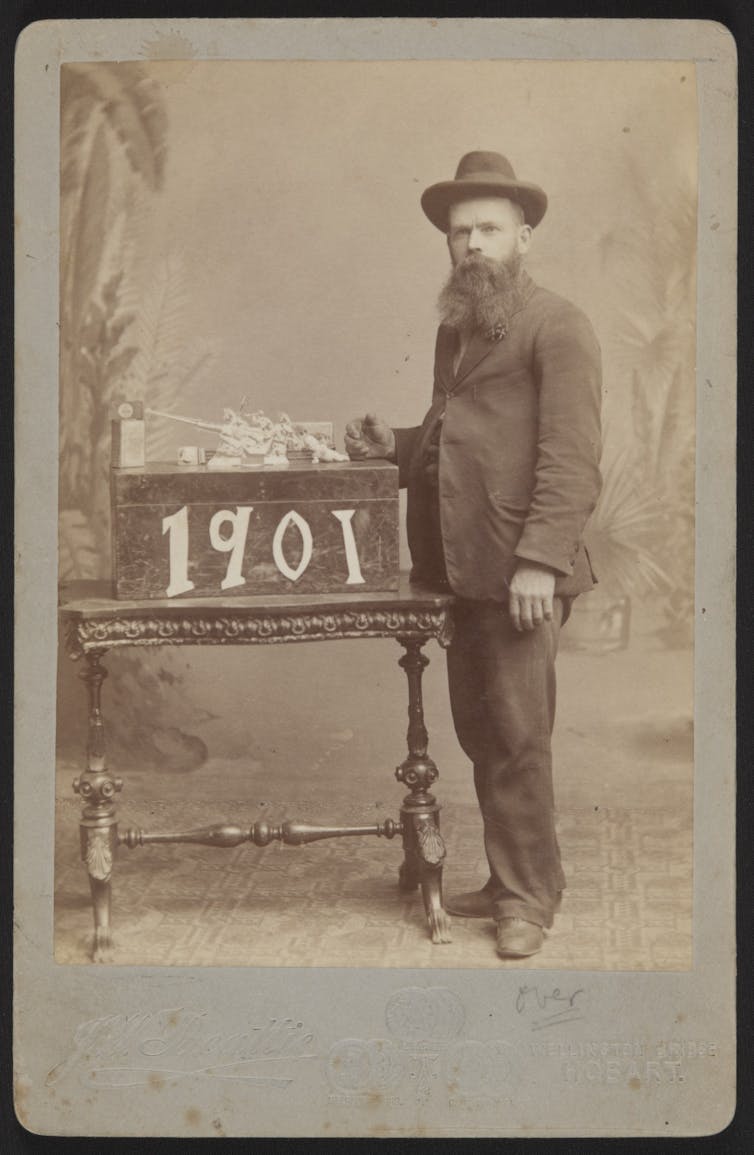

Thomas Hinton (1857-1933) was admitted to the Hospital for the Insane, New Norfolk, Tasmania, on August 25 1900 after being found to be of “unsound mind”. He had a “mania for having his photograph taken in all sorts of dress and without dress”.

One photograph, dated August 9 1900, is addressed to Miss Headlam; the admissions record detailed that “Hinton has been sending indecent photos to a Miss Headlam”. Miraculously, these 15 photographs were preserved and were acquired by the National Museum of Australia in 2013.

Four are now on public display for the first time in the Art Gallery of NSW’s exhibition The photograph and Australia, in the theme of “People and Place” in the 19th and early 20th centuries. This gallery presents the proliferating photographic techniques being used to document personal and official histories all over Australia.

The Hinton photographs are presented as one individual’s response to Federation - but the full story behind these images is yet more complex.

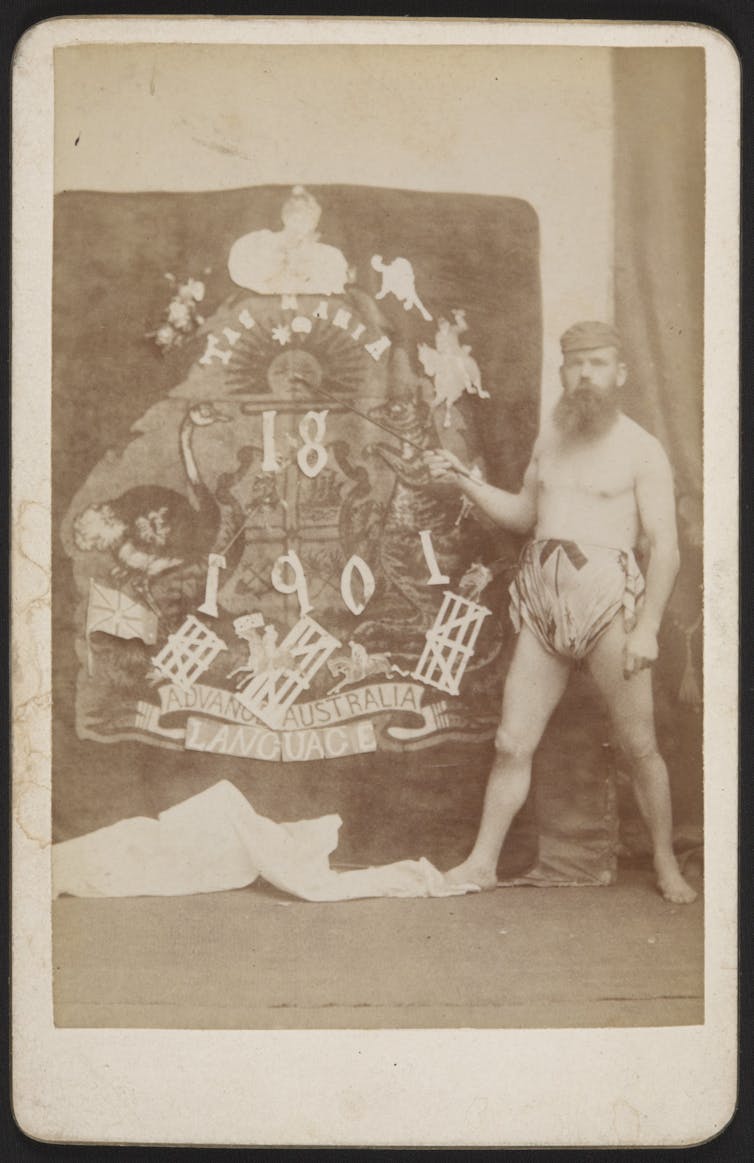

They use the conventions of studio portraiture to respond to Australia at the dawn of the 20th century. Immediately apparent in the images are the Advance Australia coat of arms and various British, Australian and Tasmanian symbols, such as flags, flora and fauna. Less readily determined is the intent of the frequent subject of these photographs, Thomas Hinton.

Hinton must have created the photographs over a period, as they are mounted on cards from studios in both Hobart and Launceston. Some props reappear throughout the photographs, indicating that they were Hinton’s own and that he deliberately constructed these dioramas.

Conventional studio props (the carved table and pedestal, drapes, and backdrop) were also included. But when it comes to the dress and poses adopted, Hinton is on his own, seeming to draw inspiration from sculptures of idealised heroic figures for his loincloths and stance (one can only wonder what the photographers thought of Hinton’s use of their studios).

Hinton’s photographs, and what we can know about his life from other sources, give a rare glimpse into the life of someone suffering a mental illness at that time. His medical records tell us that he was admitted to New Norfolk twice, and further evidence documents he had been previously been admitted to asylums in Sydney and Melbourne.

They reveal that in 1900 Hinton was 43 years old, single, and an engineer or engine driver in Tasmania’s midlands. It seems that his condition was episodic, allowing him to work for periods.

Tasmania’s mental health care was shaped by its origin as a penal colony: as the government had introduced societal ills with the transportation of convicts, so it was considered it should bear the costs of caring for the insane. A hospital was built at New Norfolk in the 1820s and was solely an asylum from the 1840s.

By the late 19th century, partly because of Darwin’s theory of evolution, mental illness was considered to be inherited, and thus had a poor prospect of recovery. This led to a tendency to conceal the mental illness of a family member. Patients vastly outnumbered staff, allowing little prospect for individual treatment or even attention. So patients would have little opportunity for self-expression, or for such work to be preserved.

Hinton’s photographs are thus an extremely rare example of a creative work by a person of “unsound mind”. It seems fitting then, that they should relate to a turning point in Australian history. The prominent repetition of 1901 in the photographs, given their creation in 1900 and use of Australian imagery, seems to indicate that they are a comment on Federation, especially given that it was a topic of public discussion.

Similarly, the Advance Australia coat of arms was nationally recognisable. While the phrase “Advance Australia” is now associated with the national anthem, its history dates to well before the song was adopted in 1984. It was used from the 1820s and was best known for its use on the unofficial Australian coat of arms.

It features on a number of items in the Museum’s collection – platters, pendants, dog tags, a remarkable embroidery. “Advance Australia” suggests the colonists’ belief in the continent’s promise and future identity as a unified, independent nation.

There are no other known photographs of Thomas Hinton, so this collection may be the result of a short-lived mania. They are certainly specific to the moment of Federation in Tasmania. The photographs employ familiar Australian iconography, but in an inimitably personal manner – his version of “Advance Australia” is painted on an inverted map of Tasmania and features an ostrich instead of an emu.

In almost all the photographs collage adorns different parts of the banner or other elements of the tableau. Combined, the collection offers a tantalising sense of almost intelligible meanings. They give a response refracted by mental illness to matters of national importance. A historically voiceless figure, the “madman” here was creating a visual record that has survived against the odds.

The Photograph and Australia is on display at the Art Gallery of NSW until June 8. Details here.

See also:

The Photograph and Australia: the curator and the exhibition