In the ongoing debate on the law’s response to sex work, it has not been forgotten that sex workers have pressing health needs. However, the debate is still very much focused on sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and simplistic, individualised responses to violence. As research I and others have produced shows, sex workers’ needs are more complex than this, and require imaginative and ambitious responses.

While taking care of sexual health is paramount for people who sell sex, the treatment of STIs is only one aspect of health that needs to be addressed. Violence, problems with drugs and alcohol, unstable housing and mental health are often far more significant. These problems may be worsened by inadequate social policies, and an enforcement-based approach to sex work that further marginalises sex workers.

The available data suggest that among sex workers in the UK, the prevalence of STIs is in fact low – even among groups perceived to be at greater risk, such as migrants. Several co-authors and I conducted a survey of UK-born and migrant sex workers from Eastern Europe, and our findings suggested that STI prevalence was relatively low across both populations. In fact, rates were no higher among our respondents than among women attending GUM clinics. The primary concerns among our participants were not STIs, but instead arrest and the risk of violence by clients and other partners.

Findings from our qualitative interviews among migrant female sex workers showed they were mostly concerned about their friends and family members finding out about their work, and the shame this would bring. The stigma associated with sex work combined with the safety concerns, and the two together led to stress, depression and mental health problems that far outweighed concerns about sexually transmitted infections.

This research was among “off street” women, working in flats or saunas. These are a privileged locations to work in as far as sex work goes: wages are higher, security is better, and women tend not to inject drugs as overt drug use is generally not tolerated. In contrast, the vast majority of “street” sex workers use drugs, and evidence shows they experience more violence from clients and are more likely to have STIs. As they are more visible, they are also more prone to arrest from the police, resulting in criminal records and the various negative social consequences that these entail – including losing custody of children.

What works

To help sex workers deal with these issues, we need interventions that specifically address their complex and interrelated health needs. There are already some excellent examples in the UK, including the Praed Street Project and Open Doors in London, which provide a range of clinical and social services. Both these projects have regular drop-in sessions where women can have a cup of tea, pick up condoms, make an appointment to see a counsellor or a lawyer, receive help to liaise with social services, and receive help with housing.

Many of these services also do “outreach”, with project staff going out to flats or street locations where sex work is conducted; some provide STI testing and treatment there, or just let sex workers know about the range of services offered. Crucially, our research has shown this kind of outreach service is associated with reduced STIs, even among those women who also use the fixed site services.

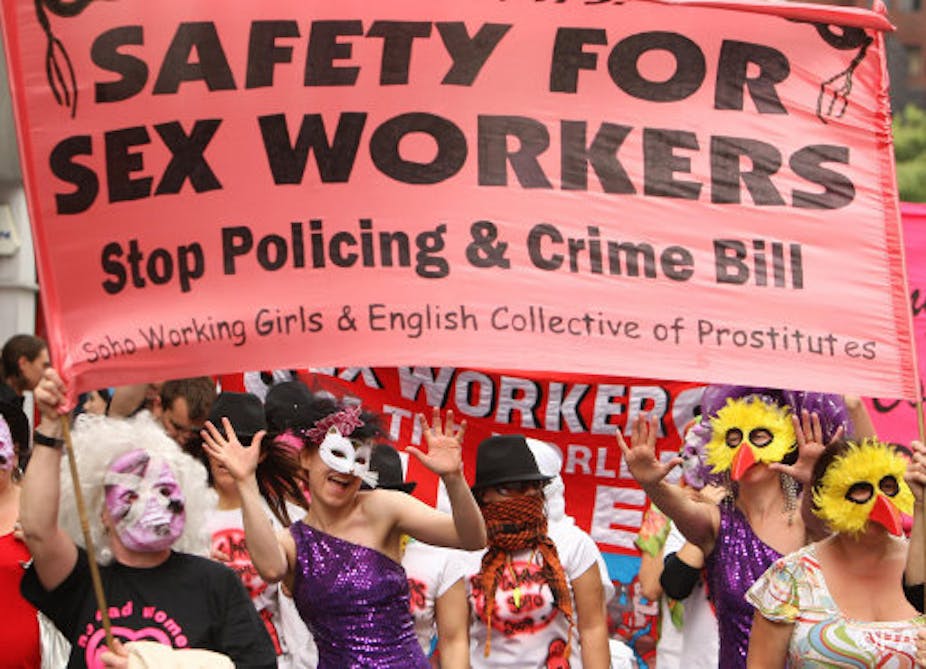

There is a substantial body of research showing the importance of targeted and specialised services for sex workers. But there is also an urgent need for structural interventions – changes at a policy level to foster an environment in which sex workers can work safely and protect their health.

For example, when tackling the issue of violence against sex workers, services must provide support to victims by dealing with the physical/emotional consequences of the attack and helping sex workers report the crime to the police, since they are often too scared to do so on their own. Many services do exist to provide this. However, in parallel to working with individual victims, information about the attacker can be distributed to other women warning them to avoid clients answering to the description as a form of community action. This has been done for many years through the “Ugly Mugs” scheme – an example of an intervention specifically designed to help sex workers.

In reality, to say violence is an inherent risk of sex work is reductive. Instead, we should view violence against sex workers as a consequence of their marginalisation; the gender and material inequalities that sex workers suffer expose them to violence in very specific ways, and therefore require very specific policy responses.

We need policies that simultaneously address the social welfare of sex workers and the root causes of their ill health. This would include disparities in employment opportunities and income, as well as assisted access to welfare services of various types. There is evidence for the positive effects of economic interventions developed as part of sex worker community development initiatives, for instance from the Sonagachi Project in Calcutta or the JEWEL intervention in Baltimore. These projects are working because of the comprehensiveness of the help they offer; they demonstrate what it means to go beyond providing condoms and women’s shelters, important though these things are.

Notwithstanding all the examples of sex worker health provisions, the legislation regulating sex work remains the most important factor in sex workers’ health and safety. On the basis of the work I have done, there is clear evidence that the UK’s current policy (and the law enforcement approaches it fosters) greatly affects the level of support or discrimination towards sex workers in general. As a result, national and local policies have a substantial impact on sex workers’ opportunities to protect both their health and their rights.

In the light of this, a long-term public health strategy for sex workers may include the further decriminalisation of specific aspects of sex work, such as working in organised groups and soliciting. Properly managed, these and other further measures could dramatically reduce the risks sex workers incur in protecting their health needs. By contrast, enforcement-based approaches (like the ones we currently use) demonstrably exacerbate sex workers’ critical health risks by making it harder for them to work in safer environments.

As I have found in the course of my work, there is a pressing short-term need to focus strategies on improving safer environments for sex workers – one that demands a change to every level of our current approach.