For the roughly 450,000 people of Indian origin in Australia, the highlight of Narendra Modi’s first visit as Prime Minister of India to Australia was his address at an Indian community reception in Sydney. Modi loves a big crowd and he is in his element when he is speaking in Hindi, as he did on Monday. He received a rapturous welcome from the more than 16,000 people who packed the arena.

However, the greater significance of Modi’s visit lies in the boost it is likely to give to bilateral ties. It will add much-needed substance to the relationship. Modi mentioned shared values very early in his address to the Australian parliament on Tuesday, saying that:

… democracy offers the best opportunity for the human spirit to flourish.

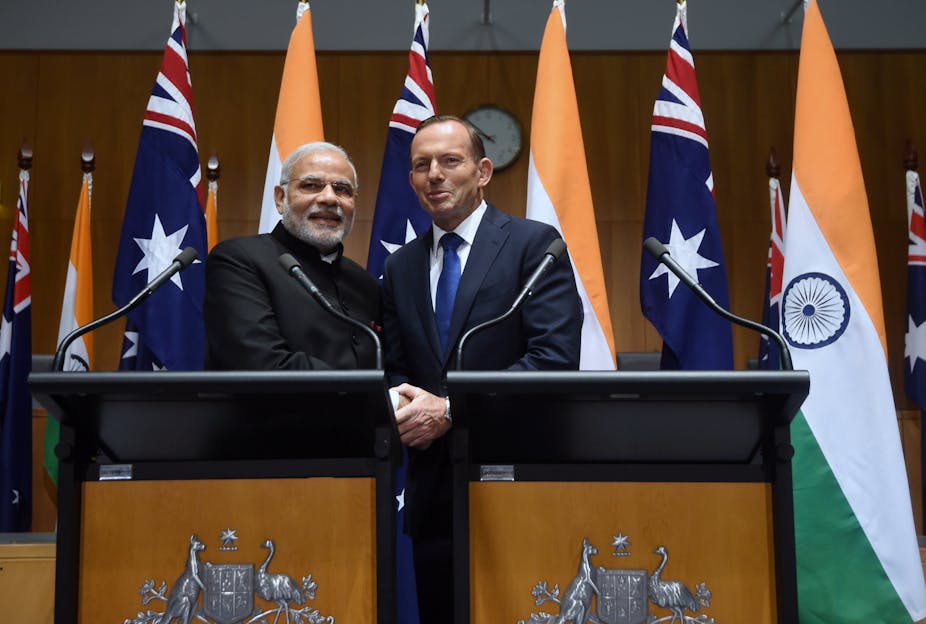

In saying this, Modi was channelling his host, Tony Abbott, who has also made democracy an important value in developing closer relations with other countries. In his Sydney address, Modi pointed to his personal journey from poverty to power to stress the importance of a free society.

Apart from shared values, Modi also emphasised the opportunities created by improving ties between the countries when he said:

There are few countries in the world where we see so much synergy as we do in Australia.

While these synergies have always existed, it is the economic momentum that Modi hopes to inject into the Indian economy that may just transform the Australia-India relationship and allow these prospects to be realised.

In welcoming Modi to parliament, Abbott referred to the Adani Group’s proposed multi-billion-dollar coalmine project in Queensland, which “will light the lives of 100 million Indians for the next half-century”. Adani will ship the coal it mines to fuel power stations in India.

While the future of that particular project hangs in the balance because of falling energy prices, the Modi government’s economic vision for India could still significantly increase Indian imports of Australian coal, gas and other natural resources – if India returns to a high-growth trajectory.

With more than 800 million people under the age of 35, India doesn’t just need growth: it needs the kind of growth that creates tens, even hundreds, of millions of new jobs. Modi knows that the hopes of legions of his supporters in India are riding on his ability to deliver on his promise of achhe din, or good days. For India’s youth, good days mean good jobs and a good quality of life.

This is why Modi told parliament that he sees Australia as “a major partner in every area of our national priority”, including education and skills development for India’s youth. If Modi’s invitation to the world’s manufacturers to come and “Make in India” is to become a reality, millions of Indians will need to be taught new skills and its universities will have to become internationally competitive.

Modi has clearly listened to the Indians who have been educated in Australia and he finds Australia to be a good partner in this area.

Another common interest that Modi emphasised in his speech is the security environment in the Indo-Pacific region. The challenges posed by the rise of China and its increasingly assertive behaviour in the South China Sea, and its growing naval forays into the Indian Ocean, have created anxiety in government and military circles in both India and Australia. Abbott was reflecting these concerns when he said:

Australia welcomes India’s strength in the Indian Ocean.

Modi went further when he called for India and Australia to expand their security co-operation. The two nations signed a defence agreement to “reflect [their] deepening and expanding security and defence engagement”.

In a thinly veiled reference to China and the territorial disputes in the South China Sea, Modi called for the states in the region to abide by “international law and norms even when they have bitter disputes”. He made similar remarks in Myanmar at the East Asia Summit before arriving in Australia last weekend. This will annoy China, but other states in the region are likely to welcome it.

Economically, Abbott called for a free trade agreement between Australia and India to be concluded by the end of 2015. Despite Modi’s upbeat assessment of the relationship, this is not going to be easy. India is unlikely to make too many concessions in the agricultural sector and in professional services.

If negotiating with the Chinese was hard, clinching a trade deal with India will test the skills of even Australia’s best negotiators. But trade deals are usually concluded when there is a political will. Modi and Abbott will have to work harder to take their new friendship to a higher level if we are going to see a free trade agreement by the end of 2015.