Poverty, unemployment and family violence are key problems facing many young Australians. To deal with these concerns in any substantial way requires concerted effort from all of us. But responsibility particularly rests with those who have the authority and the positional power to direct and sanction change.

So, what have we seen from our leaders in recent weeks? Will these suggestions help to solve the challenges confronting young people? Or is it possible they could exacerbate these very same problems?

Political responses to family violence

Recently, there has been an inadequate response to a problem facing many young people in otherwise laudable political developments.

First, the terms of reference of Victoria’s Royal Commission into Family Violence failed to name young people. Other groups such as women, children, seniors, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities and culturally and linguistically diverse communities were recognised – and rightly so. Young people did not rate a mention.

Prime Minister Tony Abbott recently announced that “violence against women and children” would top the Council of Australian Governments’ (COAG) agenda for 2015.

On Wednesday, Opposition Leader Bill Shorten called for a national crisis summit on domestic violence. Both leaders spoke about violence against women and children; neither mentioned the young people who also experience family violence.

Acknowledging it is difficult to accurately measure extent, research reports that young people experience and witness high levels of family and intimate partner violence.

This same research reports that the violence has serious consequences for young people’s health and well-being. The complex issue of young people perpetrating violence in the home is also worthy of attention.

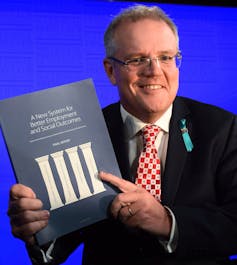

The McClure report

The review of Australia’s social security system led by Patrick McClure recommended income support should not generally be available to young people under the age of 22 in their own right. Its final report proposed a new “Child and Youth Payment” be provided to parents rather than directly to “dependent” young people as is the case now.

Whether rates of income support for young people will be higher under the new payment regime and go any way towards easing youth poverty is yet to be seen. This can be tested only when the rates are known and comparative modelling can take place.

Just as unclear is how these and other measures in the report will reduce youth unemployment – particularly in light of evidence that there are simply not enough jobs for all who want to work.

One way of understanding these recommended changes to young people’s income support is as a fictional story or myth we tell ourselves to make us think we are doing something worthwhile when what we are actually doing lacks real substance.

For example, giving young people’s payments directly to parents appears to be an extension of the delusional belief in the merits of [compulsory income management](http://theconversation.com/creeping-spread-of-income-management-must-be-challenged-24560](http://theconversation.com/creeping-spread-of-income-management-must-be-challenged-24560). In this instance parents perform the role of administering the benefit payment to young people.

We are doing something, but it lacks any value in realising the goods we should be interested in, such as reducing inequality and seriously improving the lives of young people.

A parliamentary joint committee recently found some of the federal government’s previous proposed changes to young people’s income support were incompatible with Australia’s human rights obligations. That may also well be the case on this occasion.

Recognition as an aspect of justice

Not mentioning young people in the royal commission terms of reference, in the COAG announcement and in the call for a national crisis summit renders their experiences of family and intimate partner violence invisible. Naming young people is the just thing to do and the terms of reference should be amended to do just that.

According to American philosopher Nancy Fraser, one of the two key dimensions of social justice is recognition. Justice is achieved when people or groups can see themselves identified, named and recognised.

The relevance of Fraser’s argument to the royal commission is that the terms of reference are just for the groups that are named, but they are not just for young people because they are not named.

Young people are not a homogenous group – just as women and children are not. But young people are not even on the page.

We should not generalise about young people’s experience of intimate partner and family violence, but how can we even begin to understand this complexity and diversity without the willingness to recognise young people in the first place?

Age-based prejudice and symbolic violence

These recent examples of inadequate responses to serious problems facing many young Australians reproduce prejudicial ways of knowing young people. In doing so, they potentially exacerbate the very concerns they are meant to help resolve.

The responses directly or indirectly position young people as children. Collapsing young people into the category of children infantilises them. Young people can subsequently take on and enact ways of being typically associated with childhood, such as being weak, vulnerable and unable to care for and look after themselves.

Treating young people as children also denies them all the benefits that recognition entails, such as dedicated attention and resources. In this regard, people with disabilities can attest to the importance of recognition.

It is also fair to say aged-based prejudice against young people is well on display. Academics Judith Bessant and Elisabeth Young-Bruehl argue such forthright prejudice is common and legitimises and naturalises harmful acts towards young people such as family and intimate partner violence.

Just look at the contempt often directed towards young people in the media. Just as gender inequality and community attitudes towards women are recognised as key contributors to family violence, ageism is a key factor in young people’s experience of such violence.

As I have previously argued, restricting young people’s access to income support aligns with stereotypes about them being lazy, incompetent, irresponsible, incapable of making good decisions and not to be trusted.

Prejudice against young people means their interests and concerns are too often neglected or dismissed. We should not forget that, unlike many other countries, Australia does not have a national youth policy or a minister for youth.

The treatment of young people can be understood as an example of what sociologist Pierre Bourdieu called symbolic violence. The omission of young people is an example of unequal age relations that are just taken for granted. Bourdieu suggests this is more insidious than the more obvious forms of prejudice just mentioned, because it normalises adults as those who get to say what can be said about and by young people and when. And those adults are oblivious to the pervasiveness of their dominance.

If we are serious about tackling the challenges facing many young people, such as poverty, unemployment and family violence, then we need to take a serious look at age-based prejudice. And this includes examining the understanding of and interventions in the lives of young people that such ageism engenders.