The Athens stock market plunged in its biggest one-day fall since the 1980s on December 9, following the Greek prime minister’s shock decision to call a snap presidential election for December 17.

This is a parliamentary vote; if the government’s nomination is not approved, a general election will take place early next year. If the polls are to be believed, this will bring the recently formed Syriza Party into power – with the mandate to challenge the austerity policies that have defined life in Greece in recent years.

Corruption and turmoil

Greece has been affected more than any other European country by the financial turmoil beginning in 2007. It went from being a model country for economic growth and host of an exemplary Olympic Games in 2004 to a pariah of Europe almost overnight, when the country’s budget deficit was revealed to amount to 12.5% of GDP, more than double previously estimates (it was later confirmed to be 15.6%).

When the government agreed to the biggest-ever sovereign bail-out package to date (€110 billion), it committed the country to swingeing austerity measures, including cuts in public sector pay packages and various measures to widen the tax base and reduce tax evasion.

The human and social costs of austerity policies imposed by the troika of lenders (the EU, IMF and ECB) have been severe. Greece experienced a 33% drop in its GDP in the years 2008-2014. Incomes have fallen by an average of 40% and unemployment reached more than 26% in 2013 (with youth unemployment estimated at 57%).

Meanwhile Greece’s tax collection system remains unfair and ineffective: 64% of the country’s taxpayers are employees and pensioners. They declare 82% of total taxable income and pay 78% of taxes. The austerity measures hit the poorest and most vulnerable sections of the society and unemployed youth.

But what is most troubling is that the drastic measures that have been taken have been ineffective – since they have failed to address the causes of the crisis.

Crisis of governance

The Greek crisis, which was caused by excessive borrowing by consecutive governments, is essentially a crisis of governance. For many decades, the socialist and conservative parties that governed Greece traded hundreds of thousands of state jobs for votes – and regularly passed business contracts worth tens of billions of Euros to party cronies.

A chokehold on the country’s public sector – the largest employer in the Greek economy – severely restricted the labour market. Evidently, many Greeks colluded with the kleptocracy in one form or another: though many were excluded, few refused to participate in the system of political patronage. The global financial crisis exposed the levels of Greek debt and the deeply corrupt practices of the socialist and conservative parties managing it.

The problem has been that the very people largely responsible for the crisis were charged with getting Greece out of the hole into which it had fallen. But instead of acting, they have continued to defend their political power structure without proceeding with the much-needed structural reforms. The biggest achievement of the Greek political classes therefore is their success in getting away with their misdeeds so far.

They have been aided and abetted by a compliant, self-censoring media that has distorted facts and circulated lies about Greece’s impending exit from the crisis – while the government debt-to-GDP ratio reached an all time high of 175% in 2013.

Between them these business, political and media elites have been deeply implicated in the wrongdoings of the Greek political system – yet these people dare to shame groups such as teachers and nurses as undeserving recipients of the state’s largesse.

Brink of catastrophe

These ordinary people, whose lives have been so deeply affected by these austerity measures, have been powerless to prevent their ruling classes from bringing their country to the brink of catastrophe, attracting international shame and humiliation. This powerlessness, this shame – together with the impoverishment and mass unemployment that has come with the economic catastrophe – has created fertile ground for ultra-nationalist fringe groups such as the neo-Nazi Golden Dawn.

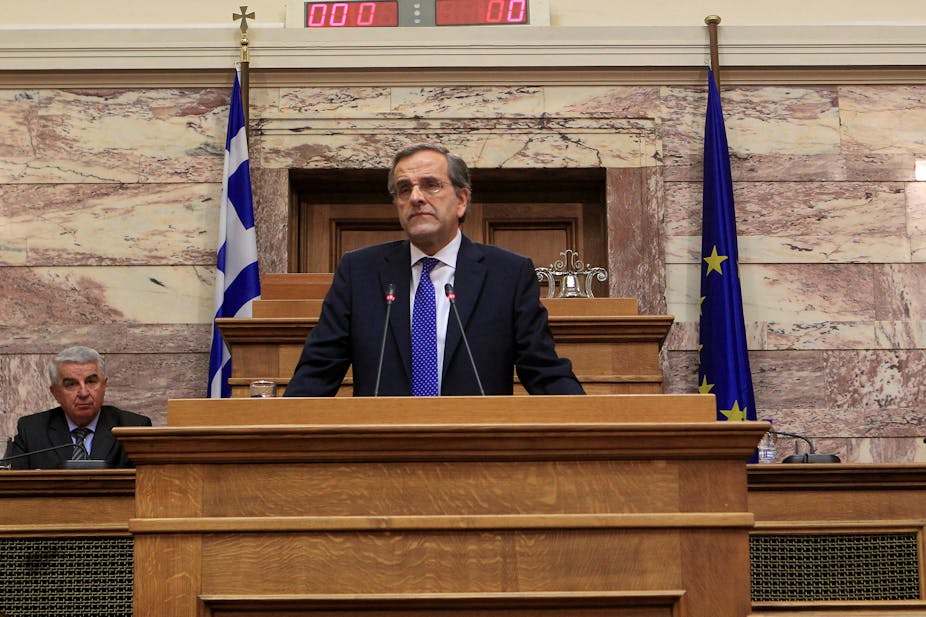

Meanwhile the incumbent conservative, New Democracy Party, which came to power with only 30% of votes in 2012, joined forces with the discredited former ruling, PanHellenic Socialist Movement to form a coalition government under Antonis Samaras.

Though elected on the promise that it would renegotiate the debt-repayment conditions, the Samaras government has instead introduced an array of new taxes for middle- and low-income employees and pensioners.

Dismayed by the unfairness of the austerity measures and the incumbent government’s leniency towards tax evasion by the rich, many potential voters have turned to Syriza, a party coalition of various radical and reformist left-wing groups. They have campaigned on a platform to protect the most vulnerable sections of the population and be more pro-active in obtaining at least a partial write-off of Greece’s crippling debt of €318.6 billion. This has proved popular with voters – Syriza topped the polls in the European elections in May.

The democratic process should run its course – this is not only important for survival of Greek society but also for the future of European institutions. While it is still uncertain how Syriza will finance its ambitious policy platform, it is clear that Greeks are no longer willing to put up with the corrupt and inept government currently in place.