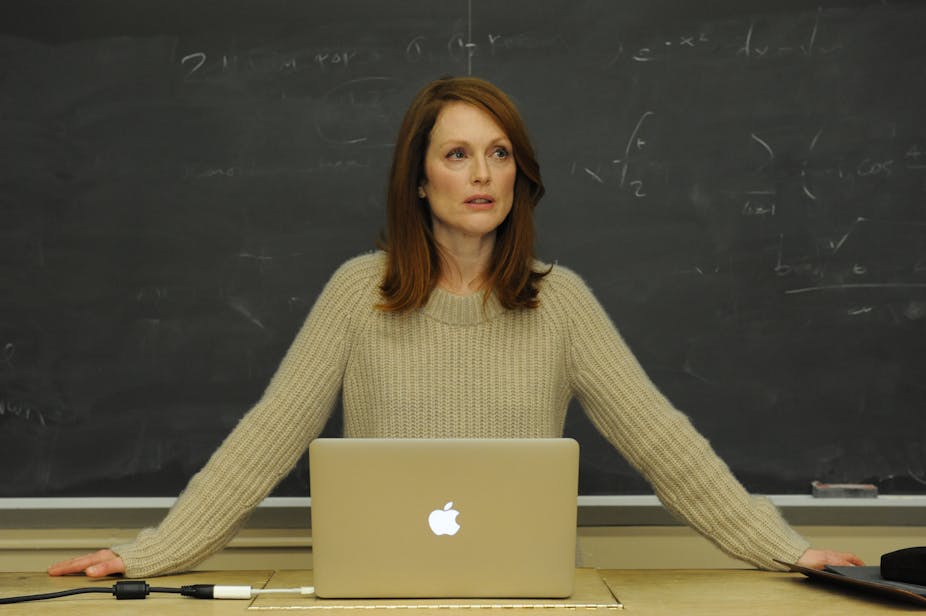

Still Alice – starring Julianne Moore – tells the story of Alice Howland, a linguistics professor diagnosed with a form of early-onset Alzheimer’s Disease. Moore has already netted a Golden Globe and is clear favourite for a well-deserved Best Actress Oscar next month.

The novel on which the film is based is one of a clutch of debuts in recent years to explore forms of neurodegenerative disease. So what role does fiction play in our understanding, and acceptance, of dementia?

Still Alice is a close adaptation of Lisa Genova’s debut novel. A Harvard trained neuroscientist, Genova initially self-published Still Alice in 2007 after failing to pique the interest of agents and publishers. But within two years word-of-mouth sales led to republication and New York Times bestseller status.

The film has received wide praise, although some critics have grumbled over the heavy-handed tragic irony. An early scene features Alice forgetting the word “lexicon” during a lecture, an implication that arguably “perpetuates the notion that dementia is more tragic when it affects the intellectual”.

Others suggest the film may be overly “pristine” and “shies away from taking risks”, while also not being plausibly representative of the typical experience of dementia in choosing to focus on an “almost perfect … privileged family”.

However the novel and film steer clear of subtlety, and for good reasons. The narrative is infused with an earnest urgency in looking to advocate for those living with dementia – and the Alzheimer’s Association is most certainly on board.

Typical popular accounts of neurodegenerative disease focus overwhelmingly on the latter stages, along with the burdens placed on families and carers.

Of course these are incredibly important issues that rightly deserve wide coverage and public discussion; to suggest otherwise would be abhorrent. But advocates have noted that this popular focus – well-intentioned though it may be – may inadvertently colour our understandings and subsequent interactions with those in early to mid stages of disease progression.

This can tragically and needlessly impose stigmas that hasten alienation and loss of social engagement.

Genova has stated in a post-script to a later edition of the book that her overarching purpose was to provide an unsentimental presentation of early onset Alzheimer’s Disease but also to complement this with an ideal diagnosis and support process. Genova aimed to demonstrate by way of fiction that there is much more we can do as a collective to help those living with dementia.

The film, especially, stresses that societal attitude to those living with dementia needs adjustment. Alice states soon after her symptoms become pronounced: “I wish I had cancer … then I wouldn’t feel so ashamed.” Later the film’s call-to-arms is a speech given by Alice to a gathering of the Alzheimer’s Association where she rails against perceptions of being “incapable, ridiculous, comic”.

The call for more dementia-friendly communities has been a significant focus of recent advocacy campaigns. Though research into clinical interventions continues, breakthroughs remain elusive while rates of prevalence are set to grow rapidly across the globe.

Advocacy groups have sought to make communities more amenable to those living with dementia, in part through awareness campaigns like this powerful one from Alzheimer’s Australia:

If Still Alice is a quite direct take on living with dementia, Fiona McFarlane’s The Night Guest (2013) and Emma Healey’s Elizabeth is Missing (2014) are two stunning examples of richly rendered explorations of dementia.

Promotional buzz around those two novels has played up their twists on genre: Elizabeth is Missing as mystery and The Night Guest as psychological thriller. Understandably this may raise concerns regarding the potential for exploiting serious conditions to enliven matters of less import.

Fiction-as-advocacy can be counterproductive if sensitive and complex issues are not addressed with due care but are instead used as convenient plot devices.

Fortunately this is not the case in either novel as the broad genre forms are deployed cautiously in the service of thoughtfully illuminating the subjectivity of dementia. Like Still Alice, these two novels adopt a point of view rooted almost exclusively to the person living with dementia, a perspective relatively rare in such accounts, fictional or otherwise.

Both books have a sometimes light humour, albeit carefully directed. This humour is often found where mutual good intentions go comically awry, such as when Healey’s protagonist Maud attempts to place a classifieds advertisement in order to help find her “missing” friend Elizabeth, whom the receptionist initially assumes is a cat.

This comic relief comes through in witnessing both characters striving to do the right thing and exhibiting patience and kindness despite mutual confusion.

Matthew Thomas’ We Are Not Ourselves (2014) adopts a more conventional route in (mostly) taking the perspective of the primary caregiver (Eileen) rather than the character living with dementia (Ed). It is by far the most harrowing of the novels mentioned here, following the progression of Ed’s disease in its entirety.

Thomas’ approach is one of unsparing sincerity, and in contrast to Still Alice glosses over nothing. Several scenes are devastating, particularly those that explore the intimate aspects of married life while living with dementia.

Nevertheless, like the aforementioned works, Thomas wants to emphasise the affective capacities that are retained. Ed’s scenes with his son are life-affirming in their urgency to communicate deep-feeling.

All these debuts are remarkably different, all are critically acclaimed. For those looking for a shorter but no less compelling entry into fiction that explores dementia one place to start is with Alice Munro’s short story The Bear Came Over the Mountain.

While we hope for clinical breakthroughs, thoughtful and considered fiction can serve as one (of many) forms of advocacy to help those living with dementia.

Still Alice is released in Australian cinemas today.