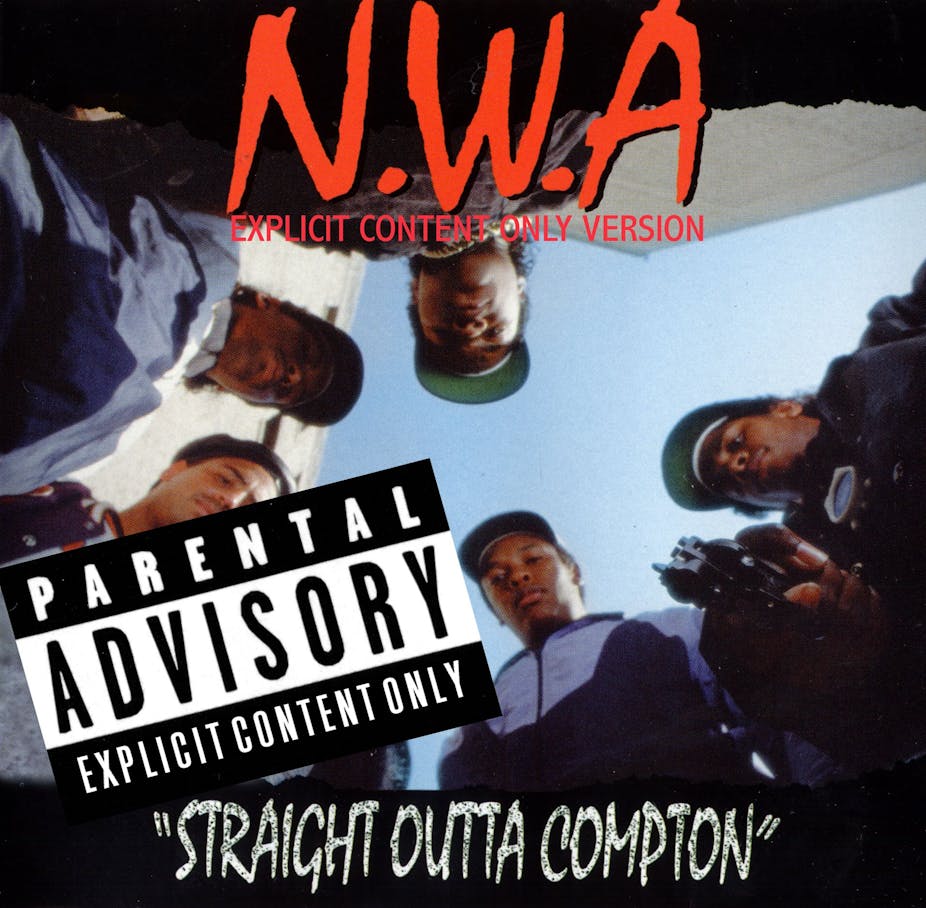

On the eve of the national Australian release of F. Gary Gray’s Straight Outta Compton – a biopic about legendary LA rap group NWA that takes its title from one of their most popular albums – a few questions come to mind.

Why is this film being released now? Is it in response to the Black Lives Matter movement spreading across the US via social media, in turn a response to racist police violence in Miami Gardens, Ferguson, Baltimore?

If so, what kind of a response is it?

Is it promoting a message of greater civic unity in opposition to the identitarian politics often favoured by governments (and their most potent civic arms, police forces)? Or is it simply Hollywood cashing in on a social trend, fad, fashion that has arisen as a result of civil unrest?

Since Italian political theorist Antonio Gramsci discussed it nearly a hundred years ago, the function of cultural hegemony has become so obvious that discussions of it appear rather banal.

It is as self-evident, under capitalism, as the associated notion of “selling out” that has been so popular in discourses about commercial “art” in general. Anyone who knows anything about the history of LA rap (as a populist political medium) knows how quickly its subversive impulses were colonised by and connected to the machine against which it was putatively rallying.

As an 11-year-old, middle-class white boy growing up in Sydney’s suburbs circa 1993, I was certainly attracted to the rap “fad” – the music of NWA was incredibly thrilling. It offered an anti-authoritarian message that still seemed to be based around the rabid (and rabidly masculine) assertion of self. Throw in a dash of cultural voyeurism, and you have a potent, intoxicating mix for a kid on the verge of puberty.

Furthermore, biography, of course (including the biopic, its most formulaic incarnation), is always about great (or at least awe-some) people transcending an unpleasant or mediocre social reality. It celebrates at its core the ideology of the individual reigning triumphant over the social and relational.

Biographies thus tend to serve the function of keeping downtrodden people – most people in the world in fact – falsely dreaming that they, too, can “make it.” As Nike – sneaker company, rather than Greek goddess – tells us: “Just do it.”

If you don’t “just do it,” it’s obviously because you didn’t have enough talent, or didn’t work hard enough.

The biography industry (in ways eerily similar to the self-help industry) elides the fact that for every Lebron James, there are 10,000 amazing basketballers who don’t get the opportunity to earn US$24 million a year, because of injury, or inadequate coaching, or simply a generally draining life-context. Steve James’ brilliant documentary Hoop Dreams (1994) plays this out to devastating effect.

That’s the nature of capitalism, which, based as it is on the notion of the virtue of competition, is (by definition) fuelled by the pursuit of inequality.

So: does Straight Outta Compton promote positive anti-fascist activism? Or does it simply channel our negative affects, our despair, reconfiguring them in a way that sells, in a form that is shallowly uplifting, falsely optimistic – and therefore a symptom of the crippling cynicism of our current age?

Is Straight Outta Compton simply another vessel for our affective exploitation? Or, to quote Ice Cube from NWA’s anthem, Fuck tha Police, does it “have something to say?”

We’ll have to wait until tomorrow to find out.

See also:

Prophets of Pain: the art of NWA’s Fuck tha Police.

Straight Outta Compton is in Australian cinemas from September 3.