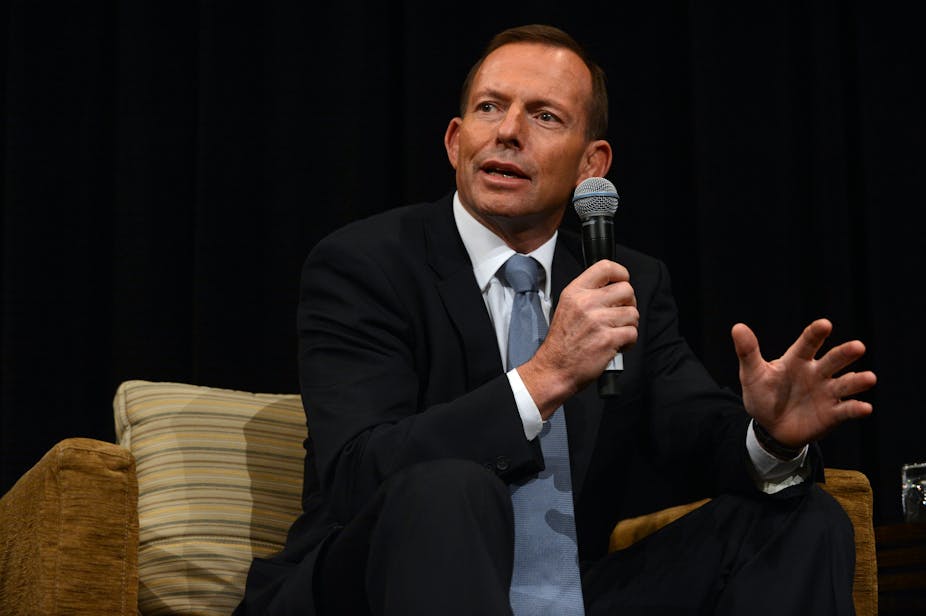

In last night’s budget reply, Tony Abbott crowed he will “put the house back in order” and that the “budget will be in better hands under a Coalition government than under Labor”. It was a very measured response that, for the first time, gave the nation some idea of what a prospective Coalition government might do in these tough fiscal circumstances.

He hoisted the government with its own petard, but indicated that the Coalition would probably accept Labor’s $43 billion in cuts and taxation increases, would legislate to implement any that were not passed before the election if it formed government, and would not commit to reverse any of them. He clarified the Coalition “reserved the right to implement all of Labor’s cuts” because there is “now a budget emergency”.

Before we deal with the detail, the first point to make about Abbott’s address is that it did engage with the Budget – a feature that Labor will probably not appreciate. Abbott accepted, modified or rejected Labor’s principal measures, giving Labor much to ponder over.

Past budget replies have not actually tackled the government’s budget; rather, the primetime TV slot has been used to as an election pitch to the nation or to attack the government politically.

However, this time Abbott chose to engage with the attributes of the budget, suggesting what he would do with the items that Labor has put on the table. These included Labor’s own budget cuts; increased taxes (“savings measures”); the NBN; the Gonski education reforms; the Baby Bonus; the 0.5% increase to the Medicare levy; and the funding for DisabilityCare.

The big news item was that carbon tax compensation to households will be preserved (if Abbott can secure passage of the tax’s repeal through the Senate).

This avoids the prospect of going to an election seemingly about to take dollars away from aged pensioners and low-income households. He confirmed, however, that in dismantling the mining tax he would also suspend the supplementary cash hand-outs to be paid to people on benefits.

Abbott claimed electricity prices would come down, a heroic assumption given most suppliers are still public enterprises that act as quasi-monopolies and can dictate prices. The threat to review their pricing by the Productivity Commission may be a worthwhile tactic.

Abbott has committed to pulling some extra $5 billion out of the budget to cover the abolition of the carbon tax, including deferring superannuation and removing the low income government contribution to superannuation and scrapping the green loans program. These may not seem to be clever moves.

In many ways, these changes have become sacrificial lambs picked out to satisfy the need to preserve the compensation payments the Gillard government introduced. They are likely to be short-term sacrifices as each has a worthy policy goal in enhancing long-term retirement incomes and reorienting the economy towards environmental sustainability.

Further confirmation was given that a Coalition government would cut 12,000 jobs from the public service, which would still see it larger (by 8,000 jobs) than when John Howard lost office. There was also a hint that the Coalition would revisit the GST – perhaps after a white paper – perhaps proposing either to increase the rate or include all those areas currently excluded to broaden its application. However, any such proposal would require a mandate from the next election and from the state premiers.

Much of Abbott’s economic strategy rests on a spike in consumer and business confidence upon the return of a conservative government. As economic activity picks up, revenues will improve further and restore the budget to balance. This may well eventuate, but it is an assumption — not yet fact. If any government squeezes the economy too hard through spending cuts or tax increases, it risks tipping the economy into recession - as John Howard nearly did when he made substantial cuts in 1996-97.

Commentator opinion to the speech has been generally positive. Annabel Crabb said the reply “was genuinely interesting”; Laura Tingle said “Abbott finally broke cover on some of his budget plans”; and Michelle Grattan called it a “backflip on carbon compensation”. Alan Kohler remained sceptical, saying that both the budget and Abbott’s reply were all “smoke and mirrors”.

Nevertheless, strong rhetoric underpinned Abbott’s speech. Some of his memorable lines included: “the Second World War was more temporary than this government’s deficits”; “parents do not mortgage their children’s future, neither should government”; “if a public company made these sorts of claims [the government has], its directors would most likely face serious charges rather than asking to be re-elected”; and “I am offering what should be normal: careful, collegial, consultative, straightforward government that says what it means and does what it says”.

But there were also many of the hoary old lines about the government’s money not being their money, that governments don’t create wealth, people do, and “you can’t spend what you don’t have”. These appeals to populism were sprinkled into what was otherwise a thoughtful response to the budget’s strategy in a fiscally challenging set of circumstances.