The Australian Music Vault launched this week in Melbourne, with music industry stalwarts and Vault patrons Molly Meldrum, Archie Roach, Kylie Minogue, Michael Gudinski and new addition Tina Arena on hand for the festivities. The Vault is a dedicated space at the Performing Arts Centre that will house a “free permanent exhibition, digital and interactive experiences and an extensive learning program”, according to a press release.

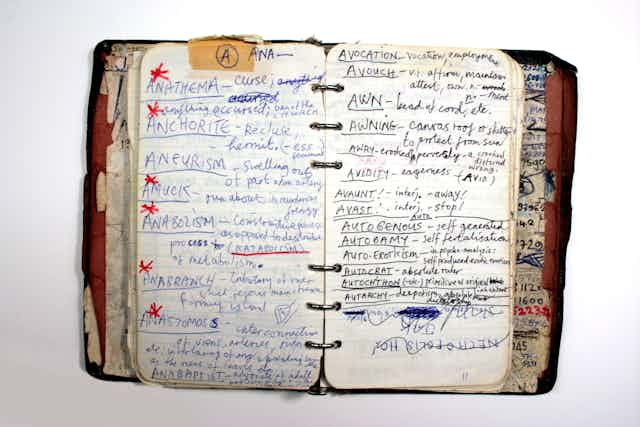

This first iteration of the Vault contains an impressive array of artefacts that cover a range of genres and eras from Australia’s popular music history. These include Chrissy Amphlett’s schoolgirl tunic, Dami Im’s gown from her Eurovision performance (a personal highlight), notebooks and lyric sheets from artists such as Nick Cave and Wendy Saddington, and footage from the Sunbury festival. Interactive elements in the exhibition space allow visitors to access archival footage and, of course, hear the music that is being celebrated.

But what does it mean that such an institution is being launched in Australia now?

Museums and other bodies that catalogue and tell the story of the past perform important identity-forming functions. They tell us who we are, where we have come from and what is deemed to be historically important.

For a long time, popular music – and popular culture more generally – was left out of such stories. It was regarded as overly commercialised, disposable, and not worthy of the same type of preservation and celebration that other forms of art were accorded.

Over time, however, as musical forms such as rock proved more durable and long-lasting than initially anticipated, and as their young audiences grew up, the incorporation of popular music into once “high brow” cultural institutions started to become more common.

This trend has increased as cities such as Liverpool have demonstrated the economic worth of promoting popular music history as a tourist attraction, and as travelling exhibitions such as Bowie Is have become blockbusters. There are now many dedicated institutions that celebrate popular music’s history, including the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in Cleveland and the Museum of Pop in Seattle.

In Australia, the path towards the Vault has taken longer than in some other places. This is partly to do with the way debate about popular music’s worth has also been tied up with tricky questions of national identity, with the local industry long struggling to find a unique way to translate music with its roots so strongly in North America and the UK. Popular music has been, at various points, a way of connecting to the “motherland” through bands like the Beatles, or as a flashpoint for debates about the Americanisation of Australian culture.

For a long time, the touchstone of success for Australian musicians was to make it overseas, and to be accepted on the terms that these markets and audiences set. Such success did indeed eventuate for acts like the Seekers, The Easybeats, Olivia Newton John, AC/DC, INXS and Kylie Minogue.

But well into the 1990s the question remained: what is it that defines Australian popular music? Is there even such a thing as an Australian sound? Or do we just produce imitations of what we hear from other places?

This is a question that the Australian Music Vault tackles head on throughout its exhibitions. Visitors are explicitly asked to listen for what it is that might give Australian music a distinctive quality. It is a question that also becomes easier to answer when looking at the local scenes and national touring circuits that have developed over time.

As a maturing industry and growing population made it more feasible to have a career making music in this country without feeling compelled to make the move overseas, more and more music emerged that spoke to local identities and concerns. Australian accents have become more discernible and songs more likely to reference Australian places and issues. Artists such as Midnight Oil and Courtney Barnett have shown that putting “Australianness” on display is not necessarily a liability on the international stage.

Speakers at the launch of the Vault noted that it seems overdue for us to have a space that celebrates the achievements of Australian musicians. The Vault exists partly because popular music has undeniably helped shape how we think about ourselves as a nation, and how we represent ourselves to the world.

This will always be an imperfect project; it is extraordinary, for instance, that in the search for an “Australian sound” the voices and musics of the original inhabitants of this continent have been so infrequently included.

The curators of the Vault have clearly considered these issues of inclusion. This first round of exhibits includes a number of Indigenous performers including Yothu Yindi and No Fixed Address, as well as Roach, and there is a strong representation of women artists such as Amphlett, Little Patti, Judith Durham and Ngaiire.

In doing this, they show that the institution has the potential to reframe as well as celebrate our relationship to this music, and to move us past the pub rock canon often put forward as the defining sound of Australia.